Learning Objectives

After reading the chapters and completing exercises in Unit 5, the reader will be able to:

IDENTIFY the current road safety partner agencies and define their role in addressing safety problems

DEFINE three areas of road safety research

DEFINE the characteristics of strategic communications

RECOGNIZE potential avenues for advancing road safety efforts

Chapter 13 - Who Does What

The greatest gains in road safety occur when transportation agencies work together rather than tackling problems alone. This can be challenging given the fragmented nature of transportation governance in the U.S. There are numerous agencies operating in different focus areas and at different levels. This chapter presents an overview of the various agencies and organizations that have a direct hand in advancing road safety and the initiatives that they undertake.

U.S. transportation agencies are typically structured around particular focus areas, such as roadway, vehicles, or road users. This approach is also seen on the international scale—the United Nations (U.N.) used a generalization called the “Five Pillar” structure as part of the Decade of Action for Road Safety.1 The U.N. recognized that efforts to improve road safety must address various pillars including road safety management, safer roads and mobility, safer vehicles, safer road users, and better post-crash response.2

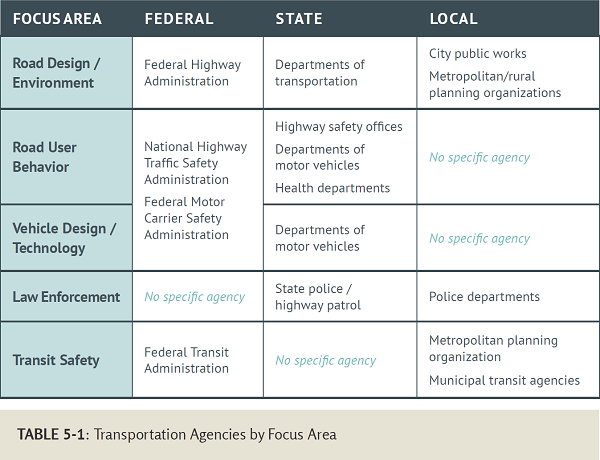

Likewise, U.S. transportation agencies are organized to address focus areas that are similar in theme to the U.N. five pillars, though not the same. Table 5-1 shows how agencies at all levels (Federal, State, and local) address five focus areas in road safety.

Federal Agencies

The Federal role in implementing road safety initiative is carried out largely through the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) and the many agencies under that department. These agencies are each tasked with a specific focus area as the Federal Government seeks to address safety issues for various modes of travel. These agencies include:

- Federal Highway Administration

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

- Federal Transit Administration

- Federal Railroad Administration

Federal Highway Administration

Focus Area: Road Design and Environment

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) works to reduce highway fatalities through partnerships with State and local agencies, community groups, and private industry. The FHWA Office of Safety advocates designs and technologies that improve road safety and administers safety programs, such as the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP). FHWA's Resource Center also provides technical assistance, technology deployment, and training. FHWA has a significant role in safety research through the Office of Safety Research and Development, which develops and implements safety innovations through teams of research engineers, scientists, and psychologists.

In addition, FHWA oversees the Local and Tribal Technical Assistance Program (LTAP/TTAP), which provides information and training programs to local agencies and Native American Indian tribes to improve road safety.3 Further, FHWA maintains division offices in each state to deliver assistance to partners and customers in highway transportation and safety services at the State level.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

Focus Areas: Road User Behavior and Vehicle Design and Technology

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) focuses on the safety of the vehicle, driver, and road user. NHTSA investigates safety defects in motor vehicles, establishes and enforces safety performance standards for motor vehicles and motor vehicle equipment, sets and enforces fuel economy standards, collects data, and conducts research on driver behavior and traffic safety, and helps states and local communities reduce the threat of impaired driving and other dangerous road user behaviors.4

NHTSA carries out research and demonstration programs in many behavioral areas including impaired driving, occupant protection, speed management (shared with FHWA), pedestrian, motorcycle and bicycle safety, older and younger road users, drowsy, and distracted driving. NHTSA is also the lead Federal agency for emergency medical services (EMS) and 9-1-1 systems.

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration develops, monitors, and ensures compliance with commercial driving licensing standards.

Focus Areas: Road User Behavior and Vehicle Design and Technology

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) focuses on reducing crashes, injuries, and fatalities involving commercial use of large trucks and buses. FMCSA develops and enforces research-based regulations that balance safety and efficiency. The agency manages safety information systems to enforce safety regulations with regards to drivers who have high risk in factors, such as health, age, experience, and education.

FMCSA also targets educational messages to carriers, commercial drivers, and the public.5 Some key programs administered by the agency include:

- Commercial Driver's License Program: FMCSA develops, monitors, and ensures compliance with the commercial driving licensing standards for drivers, carriers, and States.

- Motor Carrier Safety Identification and Information Systems: FMCSA provides safety data, State and national crash statistics, current analysis results, and detailed motor carrier safety performance data to industry and the public. This data allows Federal and State enforcement officials to target inspections and investigations on higher risk carriers, vehicles, and drivers.

- Safety education and outreach: FMCSA implements educational strategies to increase motor carrier compliance with the safety regulations and reduce the likelihood of a commercial vehicle crash. Messages are aimed at all highway users including passenger car drivers, truck drivers, pedestrians, and bicyclists.6

The Federal Transit Administration seeks to improve public transportation, such as buses.

Federal Transit Administration

Focus Area: Transit Safety

The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) seeks to improve public transportation by assisting State and local governments with planning, implementation, and financing of public transportation projects.7 FTA manages many transit-oriented safety programs including:

- Bus and Bus Facilities: This program provides capital funding to replace, rehabilitate, and purchase buses and related equipment and to construct busrelated facilities.

- Public Transportation Emergency Relief Program: This program helps States and public transportation systems pay for protecting, repairing, and/or replacing equipment and facilities that may suffer or have suffered serious damage because of an emergency including natural disasters.

- Research, Development, Demonstration, and Deployment Projects: This program supports research activities that improve the safety, reliability, efficiency, and sustainability of public transportation.

- Transit Safety and Oversight: FTA has the authority to establish and enforce a new comprehensive framework to oversee the safety of public transportation throughout the United States as it pertains to heavy rail, light rail, buses, ferries, and streetcars.8

Federal Safety Programs

Federal agencies advance road safety through numerous programs and initiatives. Federal programs can be very influential due to large funding sources provided by Federal legislation. These funds are often distributed to State and local levels to implement various improvements to roads and intersections.

Specific funding programs can change with each new piece of transportation legislation. However, it may be useful to look at an overview of some of the types of current and past funding programs. Below are listed a few programs that have been widely used through the years to develop and implement improvements to road safety:

- Highway Safety Improvement Program (FHWA)

- Traffic Records Improvement Grants (NHTSA)

- Safety Data Improvement Program Grant (FMCSA)

Highway Safety Improvement Program (FHWA)

HSIP is a Federal program focused on infrastructure improvements that will lead to significant reduction in traffic fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads. HSIP is Federally funded and administered by FHWA, but it is implemented by the State departments of transportation per the strategies laid out in the State's Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP). Funding is provided for safety-related infrastructure improvements, such as sidewalks, traffic calming, or signing upgrades. The States are required to develop a data-driven, strategic approach for improving highway safety through the implementation of such infrastructure improvements.9 States are also required to report to the U.S. Secretary of Transportation on progress made implementing highway safety improvements and the extent to which fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads have been reduced.

Data-driven

An approach of which the priorities are determined by examination of crash data or other objective and reliable safety data, rather than priorities set by preferences of a few parties, current “hot” topics, or high profile rare events.

Traffic Records Improvement Grants (NHTSA)

NHTSA administers Federal funding to encourage States to implement programs that will improve the timeliness, accuracy, completeness, uniformity, integration, and accessibility of State data used in traffic safety programs. The Federal SAFETEA-LU legislation established this program of incentive grants, and the funding continued under subsequent legislation. The funds were to be used to evaluate the effectiveness of efforts to make safety data improvements, to link safety data systems within the State, and to improve the compatibility of the State data system with national data systems and data systems of other States. A State may use these grant funds only to implement such data improvement programs. To qualify, a State must meet certain requirements including a functioning Traffic Records Coordinating Committee (TRCC), a strategic plan to address data deficiencies, and a regular traffic records assessment.10

Safety Data Improvement Program Grant (FMCSA)

The Safety Data Improvement Program (SaDIP), administered by FMCSA, provides financial and technical assistance to States to improve data collected on truck and bus crashes that result in injuries or fatalities. The assistance is provided to State departments of public safety, departments of transportation, or State law enforcement agencies. SaDIP funds have been used to hire staff to code safety performance data, purchase software for field data collection, and revise outdated crash forms.

FMCSA maintains the Motor Carrier Management Information System (MCMIS) and supplies access to the system for designated employees in each State through SAFETYNET, an online network of safety data. States use MCMIS and SAFETYNET to enter data on motor carriers, drivers, compliance reviews, inspections, and crashes. At the national level, FMCSA uses the data to characterize the safety experience of commercial motor vehicles, and to help States with the task of identifying high risk carriers and drivers. The data are also used by motor carrier companies, safety researchers, advocacy groups, insurance companies, the public, and a variety of other entities.

State Agencies

All fifty States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico administer road safety programs. State agencies administer roadway systems, driver licensing, injury prevention programs, traffic law enforcement, and other road safety activities. However, assignment of these responsibilities varies widely from State to State. In many cases, two or three government agencies are responsible for most or all of these activities. Other States distribute these responsibilities to numerous agencies and offices. Regardless of how these responsibilities are distributed, States share a vital role in improving road safety for all citizens.

In general, State agencies that address road safety issues include:

- State departments of transportation

- State highway safety offices

- State departments of motor vehicles

- State highway patrols

- State health departments

State departments of transportation oversee design, construction, maintenance, and operation of roads.

State Departments of Transportation

Focus Area: Road Design and Environment

Each State has a department of transportation (DOT), which oversees the design, construction, maintenance, and operation of the State's roads. This agency may also be called the State Highway Administration or Department of Roads. State DOTs have many official responsibilities. For highway safety issues, State DOTs have official transportation planning, programming, and project implementation responsibility. These agencies typically oversee all Interstate highways and most primary highways (State highways). State DOTs focus on roadway safety, and thus work in direct partnership with FHWA. They serve as liaisons between the Federal and local transportation agencies and provide resources and technical assistance to local agencies. State DOTs coordinate the use of Federal HSIP funds to improve roads and intersections on the local level.

In some States, the DOT administers, maintains, and operates county and city streets or secondary roads. State DOTs also work cooperatively with tolling authorities, ports, local agencies, and special districts that own, operate, or maintain portions of the transportation network.

The State DOT typically leads the development of the SHSP, a statewide-coordinated safety plan that provides a comprehensive framework for reducing highway fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads. The State DOT also develops long-range (20 to 30 year) transportation plans and short range (five to 10 year) plans that outline the vision of the transportation network and which projects will be constructed to fulfill that vision.

State Highway Safety Offices

Focus Area: Road User Behavior

State Highway Safety Offices (SHSOs) administer a variety of national highway safety grant programs authorized and funded through Federal legislation.11 The governor of each State appoints a highway safety representative to administer the Federal Highway Safety Grant Program and numerous other highway safety programs designated by Congress. The governor's representative promotes safety initiatives in the State, such as high visibility enforcement campaigns like Click It or Ticket.

The State Highway Safety Office focuses on behavioral aspects of roadway users, and thus works in direct partnership with NHTSA. Safety programs implemented by the SHSO include:

- Encouraging safety belt, child car seat, and helmet use

- Discouraging impaired driving

- Promoting motorcycle safety

- Improving the skills of younger and older drivers

State highway patrols enforce motor vehicle laws and regulations, investigate crashes, and work to identify enforcement needs.

State Departments of Motor Vehicles

Focus Area: Vehicle Design and Technology

State Departments of Motor Vehicles (DMVs) administer State programs for driver licensing, and automobile inspection and registration. Generally, DMVs reside either within the State DOT or a department of public safety. A few States have a cabinet-level DMV.

The DMV is responsible for identifying at-risk drivers and maintaining driver records. The agency also implements driver license standards, monitors graduated licensing programs, and establishes requirements for driver education. Some State DMVs also serve as the primary owners of the statewide crash data.

Coordinated

People from many agencies come together to develop an SHSP, including those from the department of transportation, department of motor vehicles, state highway patrol, public health, universities, and others.

Comprehensive

Using all types of strategies to improve road safety, such as infrastructure improvements, law enforcement, and campaigns to change driver behavior. This is seen in the types of crashes which serve as the focus areas of an SHSP, such as speeding related crashes, which are most effectively addressed through a combination of speed enforcement, engineering modifications, and behavioral campaigns.

State Highway Patrols

Focus Area: Law Enforcement

State highway patrols (also known as State police and State patrols) operate in every State except Hawaii. State police patrol highways and enforce motor vehicle laws and regulations.

State law enforcement agencies play an important role in reducing the frequency and severity of crashes. At the scene of crashes, State police direct traffic, administer first aid, call for emergency equipment, write traffic citations, and complete crash reports.

State highway patrols also investigate motor vehicle crashes, which are important sources of State and Federal crash data. They work closely with State highway safety representatives to identify enforcement needs. They play a vital role in implementing impaired driving laws, safety belt use, and other safety programs. Certain troopers in the State highway patrol are tasked with inspecting large trucks to ensure the driver and the vehicle comply with safety regulations, such as vehicle size and weight, driver hours of service, and medical fitness.

State Health Departments

Focus Area: Road User Behavior

State health departments also play an important role in reducing crash severity. These agencies are typically responsible for statewide trauma center planning. State health departments provide training, certification, and technical assistance for EMS providers, administer injury prevention programs, and maintain trauma and injury databases. Some State health departments coordinate with other public agencies and community groups to promote young driver safety, older driver safety, child passenger safety, and pedestrian and bicycle safety.

State Safety Plans and Programs

State agencies use numerous approaches to improve road safety within their State. Often, they seek to identify State-specific safety issues and direct Federal or State funding to solve those issues. State agencies take the lead in developing statewide safety plans or programs, many of which are encouraged or required by the Federal Government. Although States differ in their specific safety improvement efforts, the following plans or programs are developed in every State:

- Strategic Highway Safety Plan

- Long Range Transportation Plan

- Statewide Transportation Improvement Program

- Railway-Highway Crossing Program

- Highway Safety Program

Although the HSIP was previously covered under Federal safety programs, it should be noted that the State plays the major role in selecting locations that need safety improvement, designing, and implementing the safety improvement, and reporting annually on all the HSIP funded projects that were constructed that year.

Strategic Highway Safety Plan

A State's SHSP is a statewide-coordinated safety plan that provides a comprehensive framework for reducing highway fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads. An SHSP identifies a State's key safety needs and guides investment decisions toward strategies with the highest potential to save lives and prevent injuries. Since 2005, Federal legislation has required States to develop, implement, evaluate, and update their SHSP.12,13

The State DOT develops an SHSP in a cooperative process with local, State, Federal, tribal, and private sector safety stakeholders. It is a data-driven, multi-year plan that establishes statewide goals, objectives, and key emphasis areas. The development of an SHSP provides a venue for highway safety partners in the State to align goals, leverage resources (i.e., combine Federal and State resources), and collectively address the State's safety challenges.14

An ideal SHSP meets several criteria:

- It addresses engineering, management, operation, education, enforcement, and emergency service elements of highway safety as key factors in evaluating highway projects.

- It considers safety needs of, and high-fatality segments of, all public roads.

- It considers the results of State, regional, or local transportation and highway safety planning processes.

- It describes strategies to reduce or eliminate safety hazards.

- It gains approval of the governor of the State or a responsible State agency.15

In order to spend HSIP funds, a State must have a current SHSP, produce a program of projects or strategies to reduce safety problems, and evaluate the SHSP on a regular basis.16

Long-Range Transportation Plans

Long-range transportation plans (LRTPs) identify transportation goals, objectives, needs, and performance measures over a 20- to 25-year horizon and provide policy and strategy recommendations for accommodating those needs. LRTPs are prepared at both the State and MPO level. LRTPs are fiscally-unconstrained and typically present a systems-level approach that considers roadways, transit, pedestrian, and bicycle facilities. LRTP's have wide scopes; the components of the plan may be policy-oriented and strategic or focused on specific projects. The types of improvements range widely, as well. Safety-focused improvements in a LRTP may be directed at infrastructure, such as building new interchanges or bringing certain highways up to current design standards, or behavioral efforts, such as addressing seat belt use or aggressive driving.

Statewide Transportation Improvement Programs

The Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) identifies the funding and scheduling of transportation projects throughout the State that support the goals identified in the LRTP. STIPs are short-range (typically an outlook of five to ten years) and fiscally constrained, meaning that the projects must have designated funding. While many STIP projects are constructed for capacity or mobility reasons (i.e., build a bypass or widen a road), there are also STIP projects that are focused on improving safety, such as widening shoulders or installing rumble strips. Projects included in STIPs must have identified funding sources (e.g., HSIP, State, or local funding).17 The State DOT identifies projects in areas outside MPOs, such as rural areas and smaller urban jurisdictions, for inclusion in the STIP.

The Railway-Highway Crossings Program funds safety improvements at crossings.

Railway-Highway Crossings Program

The Railway-Highway Crossings Program funds safety improvements to reduce the number of fatalities, injuries, and crashes at public grade crossings.18 A grade crossing is a location where a public highway, road, street, or private roadway (including associated sidewalks and pathways) crosses a railroad track at the same level as the street. These locations are high-risk spots for road users. The United States has more than 200,000 grade crossings.19 Types of crossing improvements that the Railway-Highway Crossings Program implements include:

- Crossing approach improvements

Projects such as channelization, new or upgraded signals on the approach, guardrail, pedestrian/bicycle path improvements near the crossing, and illumination - Crossing warning sign and pavement marking Improvements

Projects such as signs, pavement markings, and/or delineation where these project activities are the predominant safety improvements - Active grade crossing equipment installation/upgrade

Projects such as new or upgraded flashing lights and gates, track circuitry, wayside horns, and signal improvements such as railway-highway signal interconnection and pre-emption.20

Highway Safety Program

Each State administers a Highway Safety Program, approved by the U.S. Secretary of Transportation. The program is designed to reduce deaths and injuries on the road by targeting user behavior through education and enforcement campaigns.21 The State conducts this program through the State highway safety office. A State is eligible for SHSP grants by having and implementing an approved Highway Safety Plan (HSP). The HSP establishes goals, performance measures, targets, strategies, and projects to improve highway safety in the State. It also documents the State's efforts to coordinate with the goals and strategies in the SHSP. However, the Highway Safety Program is distinct from an SHSP. SHSPs target improvements to infrastructure and road users, and are broad in content and context, while highway safety programs focus more on road user behavior.22 An HSP might address issues such as excess speeds, proper use of occupant protection devices, driving while impaired, and quality of traffic records data.23

Local Agencies

Charlotte Pedestrian Safety

The City of Charlotte developed its Transportation Action Plan (TAP) in 2011 to describe how to reach its safety and mobility transportation goals. The plan emphasized the safety of all road users and included objectives such as constructing 375 miles of new sidewalk by 2035.24 To support the goal of pedestrian safety, Charlotte developed Charlotte WALKS, the city's first comprehensive Pedestrian Plan. This plan identified new strategies to meet the pedestrian safety and walkability goals in Charlotte's TAP.25

Local agencies, such as city and county governments, play an important role in improving road safety and identifying and selecting transportation projects. These agencies that administer roads at the local level may be called by various names: public road agency, department of public works, departments of transportation, or road commissions. Due to their smaller size, many local agencies may not have a staff member who is specifically focused on road safety. The urban nature of their jurisdiction naturally causes their efforts to be focused on different types of road safety topics than a State DOT. For example, a city transportation department would typically focus on urban elements such as sidewalks, transit accommodations, and high density access management, where as a State DOT would typically be focused on more rural elements, such as high speed curves and isolated intersections.

Most safety issues for local streets, intersections, or corridors are the responsibility of the city or county government. These agencies supplement State laws, establish traffic laws in their jurisdictions, and determine penalties for noncompliance. Local law enforcement agencies investigate crashes and submit crash data to State and Federal agencies. City and county planning and engineering staff help plan and design roads, bike lanes, and sidewalks. Many local police departments partner with State police to implement impaired driving, work zone safety, motorcycle safety, heavy truck, and safety belt education and enforcement programs. In some States, the State DOT owns many of the major roads in the city and may coordinate with the local agency to identify potential safety improvements and get them installed. Many local agencies also collaborate with the State DOT to develop a Local Road Safety Plan.

At the regional level, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) plan, program, and coordinate Federal highway and transit investments. When an urban area meets certain minimum characteristics (e.g., population), Federal law requires the creation of an MPO for the region to qualify for Federal highway or transit funds in urbanized areas. MPOs do not typically own or operate the transportation systems in their jurisdiction. MPOs play a coordination and consensus-building role in planning and programming funds for capital improvements, maintenance, and operations. MPOs involve local transportation providers in the planning process by coordinating with transit agencies, State and local highway departments, airport authorities, maritime operators, rail-freight operators, Amtrak, port operators, private providers of public transportation, and others within the MPO region.26

Other Safety Partners

Although government agencies have the support of large budgets and institutional authority to implement improvements to road safety, they are not the only entities working to improve road safety. Government agencies work with partners from a variety of fields to improve the nation's roadways including those in private industry, special interest groups, and professional organizations.

Private industry

Automobile Manufacturers

Auto manufacturers have a critical effect on road safety by designing vehicles that assist the driver in avoiding crashes and that absorb energy in crashes that do occur. Federal standards stipulate that vehicles must have certain safety improvements, such as seat belts, air bags, and electronic stability control.27 However, auto manufacturers have also implemented various non-required safety improvements. These improvements typically make use of emerging technologies or materials.

For instance, in the early 2000's, auto manufacturers began manufacturing vehicles that had “smart” technologies to improve safety, such as collision warnings and assisted braking. These technologies, which were not required by the government, addressed some of the most common crash types, such as rear end crashes. These improvements also set the stage for more advanced automated vehicle designs and technologies.

Insurance Companies

Insurance companies often assist in identifying ways to improve safety on the nation's roads. The most notable organization in this respect is the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) and its sister organization, the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI). These are organizations that study road safety issues and use insurance data to provide data-based evidence of safety by vehicle make and model. These organizations are funded by a pooled group of insurance companies and associations. IIHS runs the Vehicle Research Center, which conducts crash tests of many vehicle types to encourage auto manufacturers to produce safer vehicles and inform the consumer on vehicle safety ratings.

American Council of the Blind (ACB) and National Federation of the Blind (NFB)

The ACB and NFB represent the interests of people who are blind or visually impaired. These organizations work to inform legislators, city and State agencies, and the public about road safety issues that are unique to individuals with visual impairment. They promote policies and practices that assist visually impaired individuals in traveling safety and independently. These include enhancements, such as auditory stop announcements on buses and accessible pushbuttons that provide information about street crossing signals.

Special interest groups

Special interest groups are associations of individuals or organizations that promote their common interests by influencing the legislative process at the local, State, and/or Federal levels of government. Many interest groups also serve other functions, such as providing services and information to their members. Interest groups fill a vital role in advancing the cause of safety-related legislation.

A few examples of road safety-focused interest groups include the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, National Safety Council, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), the American Council of the Blind, and the National Federation of the Blind. There are many other interest groups involved in influencing transportation and safety legislation. These groups engage in a variety of activities, such as sponsoring independent research and evaluation, mobilizing citizens to contact their legislators in support of or against certain pieces of legislation, and disseminating policy reports in support of or against legislation affecting the safety of the road users they represent.

Professional organizations

Professional organizations bring together road safety professionals from common backgrounds or spheres of influence to foster discussion and advancement of safety issues. Members of these organizations who recognize emerging road safety issues can use the power of the group to advocate legislation or sponsor research to address these issues.

These organizations often hold regular conferences that allow safety professionals to network, share ideas, and gain knowledge from others in their field. The organizations also provide training opportunities that help advance and disseminate road safety knowledge.

There are many professional organizations covering many disciplines that relate to road safety. While this textbook is not intended to provide an encyclopedic listing, a few examples are listed below.

American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO)

AASHTO members consist of representatives from highway and transportation departments in the 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. AASHTO provides tools such as Safety Analyst, an analytical software package, and publishes the Highway Safety Manual, which provides an analytical and quantitative framework for analyzing a road's safety performance. AASHTO focuses on emerging safety issues through its Standing Committee on Highway Traffic Safety. AASHTO inspired the development of a national safety plan called Toward Zero Deaths, committed to reducing the number of highway fatalities to zero.

Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE)

ITE is an association of transportation professionals who are responsible for meeting mobility and safety needs. ITE promotes professional development of its members and facilitates the application of technology and scientific principles to the safety of ground transportation. ITE's Transportation Safety Council covers issues, such as roadside safety, pedestrian and bicyclist safety, and work zone safety.

Association of Transportation Safety Information Professionals (ATSIP)

ATSIP focuses on data and is the leading advocate for improving the quality and use of transportation safety information. ATSIP furthers the development and sharing of traffic records system procedures, tools, and professionalism. Its goal is to improve the quality of safety data and encourage their use in safety programs and policies.

Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA)

GHSA represents the State and territorial highway safety offices that implement programs to address behavioral highway safety issues including occupant protection, impaired driving, and speeding. GHSA provides leadership and advocacy for the States and territories to improve traffic safety, influence national policy, enhance program management, and promote best practices.

International Organizations

As of 2017, there is no U.S. organization that combines the narrow focus of improving road safety and a broad multidisciplinary approach. The current inventory of U.S. professional organizations is usually specific to a type of discipline, such as engineering or behavioral science. Looking beyond the U.S. borders shows that other countries have formed organizations that bring together many different disciplines to address road safety including the following:

- World Road Association (PIARC, after its former name Permanent International Association of Road Congresses), www.piarc.org/en/

- La Prévention Routière Internationale (PRI), www.lapri.org

- United Nations Road Safety Collaboration, https://www.who.int/groups/united-nations-road-safety-collaboration

- Global Road Safety Partnership, www.grsproadsafety.org

- International Road Federation, https://www.irf.global/

EXERCISES

- RESEARCH a recent road safety project in your city, county, State, or region. Identify the roles and responsibilities of the Federal, State, and/or local governmental agencies in the project. Prepare a brief report for a class presentation.

- USE your local, State, or regional highway department's website to determine its most pressing road safety concerns. Prepare a brief report that explains the concerns, how the agency identified them, the proposed remedies, and the agency's next steps.

- PREPARE a brief presentation that summarizes how your local government administers roadway programs. Identify the form of government (city, county, municipality, parish, etc.), the local agencies, and their responsibilities to roadway safety programs.

- RESEARCH a private or nonprofit interest group that works to improve road safety. Prepare a class presentation that includes a brief history of the interest group, a synopsis of important and successful campaigns, and a summary of its current work. Some examples of private or nonprofit interest groups include the Automobile Association of America (AAA), Mothers against Drunk Driving (MADD), the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS), and the American Bikers Aimed Toward Education (ABATE), and many others.

- RESEARCH your local, State, or regional transportation safety planning group. Prepare a brief report that identifies the group's current safety goal(s), explains how the group plans to alleviate the safety challenge(s), and describes the group's strategic communications plan.

- RESEARCH a private sector or industry association that works to improve road safety. Prepare a class presentation that includes a brief history of the interest group, a synopsis of important and successful campaigns, and a summary of its current work. Some examples of private sector or industry associations include the American Insurance Association (AIA), the American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA), the American Road and Transportation Builders Association (ARTBA), the National Association of County Engineers (NACE), the American Public Works Association (APWA), and many others.

- FIND OUT how professional associations like the National League of Cities, the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO), the Governor's Highway Safety Association (GHSA), and the Standing Committee on Highway Traffic Safety (SCOHTS) influence road safety policy. What are some examples of past successful campaigns?

- Using the State DOT website, RESEARCH your home State's Highway Safety Program. Prepare a brief presentation that identifies the State and describes how it is working to improve roadway safety. You may want to focus on the State's efforts with a particular road user or road safety provider. Be sure to include details about how the State identified the safety challenge(s), how the State chose its countermeasure(s), and how its efforts measure against national performance criteria.

Chapter 14 - Road Safety Research

Road safety practitioners are constantly seeking the most effective means for preventing injuries and fatalities on the road. To accomplish this, they need to understand the nature of the road safety problems and which behavioral or infrastructure countermeasures are the best at addressing these problems. When weighing two possible safety treatments, they need to know which one is more effective (would prevent more crashes) and more efficient (preventing crashes at a lower cost). Additionally, safety practitioners work with a limited budget, so they need to know which safety treatment is more cost effective, that is, how many crashes can be prevented for the same dollar spent. These goals lead to many questions, such as:

- What age range should be targeted in a young driver safety program?

- What is an effective strategy for preventing run-off-road crashes?

- How many crashes would be expected on one type of road versus another type?

- How many serious injuries could be prevented by installing additional safety measures at a signalized intersection?

Research is the key to answering these questions and providing quality information to the safety practitioner. Unit 3 of this textbook provides a look at the various types of safety data and how they can be used together. Good research analyzes one or more kinds of safety data to gain knowledge on ways to prevent crashes or decrease injuries when crashes do occur.

General Types of Road Safety Research

The intention of this chapter is not to summarize the entire field of road safety research, but rather to provide an overview that will show what types of research have been conducted within the topic of road safety.

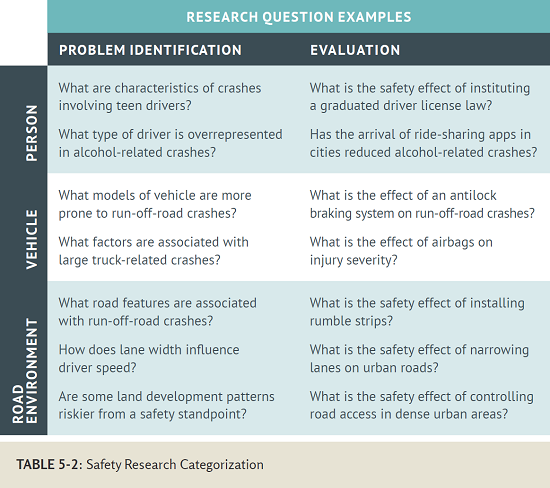

One way that these road safety research projects can be generally categorized is by grouping them by the safety factor they address: the person, the vehicle, or the roadway. For each of these categories, safety research typically focuses either on identifying safety problems or on evaluating solutions to safety problems. Table 5-2 demonstrates this classification of safety research areas and provides example questions that would drive research studies in each area.

While this chapter presents road safety research in terms of identifying problems or evaluating solutions, researchers also play key roles in developing new solutions to road safety problems. For example, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) was experiencing thousands of crashes, including many fatalities, in construction work zones and sought an alternative to the traditional work-zone barrier. University of Florida civil engineering researchers hired by FDOT developed a new type of portable temporary low-profile barrier that can redirect cars and small trucks, preventing them from crashing into the work zone and protecting the passengers in the vehicle. The barrier was advantageous in that it could be broken down into small inexpensive segments that are easy to install and move around.28 Additional research was carried out to evaluate this new type of barrier in terms of criteria like crash performance and durability.

Examples of Road Safety Research

The following sections provide descriptions and examples of research studies. These examples will give the reader a look at the types of studies that are conducted within each of the six categories shown in Table 5-2.

Research on the Person

Problem Identification

The IIHS sponsored a study to examine the characteristics of crashes involving 16-year old drivers. The researchers used crash data from NHTSA's General Estimates System (a national crash database built on sampling from police agencies around the U.S.). They compared crash involvement of sixteen-year-olds to that of other age categories of drivers and found that sixteen-year-olds were more likely to be involved in single-vehicle crashes and night time crashes (6:00pm to 11:59pm). Sixteen-year-olds were also more likely to have received a moving violation and been at fault for a crash. They were also more likely to be accompanied by other teenage passengers. Researchers also found some indications that drivers with less on-the-road experience (females in this study) were proportionately more involved in crashes.29

Evaluation of Solutions

In 1997, Michigan instituted its Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) program to address the high rate of fatal crashes involving teen drivers. This program required teen drivers to gain driving experience under relatively low risk conditions before obtaining full driving privileges. A new driver would progress through Level 1 (a learner's stage requiring extensive supervised practice), Level 2 (an intermediate stage which prohibited teenage passengers and driving at night), and Level 3 (full licensure with no restrictions). NHTSA funded a group of researchers to evaluate the effect of the GDL program on the crash risk of 16-year-old drivers. The researchers examined Michigan statewide crash data from 1996 (pre-GDL) and 1998 and 1999 (post-GDL). They analyzed the pre-GDL and post-GDL rates of 16-year-old drivers involved in crashes by unit of the statewide population. Researchers also compared to crash rates of drivers over age 25 to control for any other trends. They found that the overall crash risk for 16-year-old drivers decreased 25% by the year 1999 (two years after GDL was implemented). They also found significant reductions in many specific crash types, such as night crashes and single vehicle crashes. These findings showed a significant benefit to the GDL program and served to support GDL implementation in other States.30

Research on the Vehicle

Problem Identification

How Research Affects Implementation: Motorcycle Helmets

Motorcycle helmets are now a common road safety element to reduce serious head injuries, but they were not always so. The original interest in motorcycle helmets began when Colonel T.E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia) died after suffering a head injury in a motorcycle crash. One of the physicians who attended him, Hugh Cairns, was moved by the incident and began studying the prevalence of head injuries among motorcyclists in the British Army. His work ultimately led to helmets becoming mandatory in the British Army and the U.K.

Early motorcycle helmets were leather caps that did little to protect riders. Then in the 1950s, Roth and Lombard came up with the idea of using a crushable, energy absorbing material (Styrofoam) inside the helmet. A study in 1957 by a physician named George Snively helped this new type of helmet take hold through unusual means—testing six popular motorcycle helmets on human cadavers. The Roth and Lombard helmet with the protective lining was by far the most effective in preventing head injuries.

Many more studies have documented the effectiveness of motorcycle helmets. This eventually led to standards for motorcycle helmets and universal helmet laws.34,35

The design of a vehicle, particularly how well it protects the occupants in the event of a crash, can have a significant effect on injuries sustained in the crash. A group of researchers from the IIHS investigated the relation of vehicle roof strength to occupant injury during crashes. They examined crash data from fourteen States for single-vehicle rollover crashes involving midsize SUVs. They also used a rating of roof strength for each vehicle type in the crash data. Their findings showed that the crush resistance of a vehicle's roof was strongly related to the risk of fatal or incapacitating injury to the occupants. This research identified one statistically significant factor (roof strength) in the severity of rollover crashes. The researchers also recommended the study of other vehicle factors to determine their effect on the severity of rollover crashes.31

Evaluation of Solutions

Anti lock braking system (ABS) is a technology that was developed to combat the problem of drivers losing control of their vehicle during hard braking due to locked wheels. ABS modulates braking power to prevent a vehicle's wheels from locking up. Since this technology requires drivers to employ it correctly (i.e., step and hold on the brake rather than pumping), the Federal Government conducted a public information campaign in 1995 to inform drivers how to use ABS correctly. The NHTSA sponsored a study that took a long term look at the effect of ABS from 1995 to 2007. The researchers used crash data from two Federal databases (the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the General Estimates System of the National Automotive Sampling System) to estimate the long-term effectiveness of ABS for passenger cars, light trucks, and vans. They found that ABS reduced fatal crashes with pedestrians but increased fatal run-off-road crashes. ABS proved to be quite effective in reducing nonfatal crashes in all types of vehicles. This result is for the ABS alone; the authors recognized that electronic stability control (a technology which automatically applies brakes to individual wheels to keep the driver on the road) would soon be paired with ABS for potentially greater crash reductions.32

Research on the Road Environment

Problem Identification

Curves on the road, both horizontal and vertical, are known to be problem spots for road safety. They are particularly concerning when they occur together, such as a horizontal curve at the peak of a hill. FHWA sponsored a study to identify and quantify the road and curve characteristics that are associated with higher instances of crashes. The researchers examined curves in Washington State using crash data and roadway characteristics contained in the Highway Safety Information System (HSIS). They analyzed locations where horizontal and vertical curves occurred independently, as well as locations where both occurred in the same place. The researchers developed equations that predicted the effect on crash frequency for each type of curve combination. These predictive equations included road and curve characteristics found to affect the frequency of crashes. These characteristics included the sharpness of the vertical curve and the radius of the horizontal curve.33

How Research Affects Implementation: Safety EdgeSM

The ultimate intent of safety research is to provide solid data to affect the way that safety measures are carried out in the real world. The development of Safety EdgeSM is a good example of this.

Drivers who run off the road and then try to regain control often go too far and over-steer, leading to veering into the opposite lane or running off the road on the other side. This problem is made worse when the soil is eroded away from the pavement edge, creating a drop off. This safety concern was recognized in the 1980s, and the 1989 AASHTO Roadside Design Guide included a recommendation for adding a sloped edge to the pavement to assist drivers in regaining control onto the roadway. A few States attempted this treatment, but it was not widely implemented. Through the following years, other research showed a correlation between drop off crashes and fatalities.

In the early 2000s, several States (Georgia, New York, Colorado, and Indiana) decided to install several miles of the sloped edge as demonstration project. The FHWA sponsored a research study to evaluate the effect of the sloped edge, now called Safety EdgeSM, on run-off-road crashes. The results showed a positive effect, and this finding swayed many safety offices in favor of the treatment. Those now in favor of Safety EdgeSM worked to get other offices, such as pavement offices, on board with the idea. Eventually it became a widespread practice, and by 2015, forty States required Safety EdgeSM to some degree in their design policies.39

Evaluation of Solutions

Rumble strips are expected to decrease crashes by generating noise to alert sleepy or inattentive drivers that they are about to leave the travel lane. Rumble strips on both the centerline and shoulder ensure that drivers are alerted no matter which side of the lane they depart. FHWA, through a pooled fund from 38 States, conducted a study to determine the safety effect of installing centerline and shoulder rumble strips on rural two-lane roads. The researchers gathered data on roads in three States and compared crash performance for roads where the rumble strips were installed versus roads without rumble strips. The analysis showed that the combined rumble strip strategy was effective at reducing crashes. As expected, the greatest crash reductions were for crash types that were related to lane departure including headon crashes (37% decrease), runoff-road crashes (26% decrease), and sideswipe-opposite-direction crashes (24% decrease).36

Major Road Safety Research Sponsors and Research Programs

Most road safety research is funded by the government, through state or federal agencies. However, some research is also funded by privately run companies or foundations. The organizations that sponsor research projects are often focused on one category of research. The list below presents a look at some of the major research sponsors and their area of focus in road safety research.

Federal Research Sponsors

Federal Highway Administration

FHWA sponsors research studies on a variety of road safety topics, and their primary focus is on the roadway or the built environment. This research investigates the impact of road characteristics on road safety and seeks solutions to known safety problems. The FHWA Offices of Safety and Safety Research and Development conduct research to address issues including driver interaction with the roadway, intersection safety, pedestrian and bicycle safety, and keeping vehicles on the roadway.37 The FHWA Turner-Fairbank Research Center houses more than 20 laboratories, data centers, and support facilities, and conducts applied and exploratory advanced research in road safety, among other topics. Additionally, FHWA staff participates and provides input to many other venues of research around the nation.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

NHTSA studies behaviors and attitudes in road safety, focusing on drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and motorcyclists. Research sponsored by NHTSA identifies and measures behaviors involved in crashes or associated with injuries, and develops and refines countermeasures to deter unsafe behaviors and promote safe alternatives. The research topics include occupant protection, distracted driving, motorcycle safety, speeding, and young drivers.38

Transportation Research Board

The Transportation Research Board (TRB) is part of the National Academies of Sciences and provides advice to the nation and informs public policy decisions. TRB plays a major role in road safety research. It hosts an annual meeting where transportation professionals from around the world present new research on many different transportation topics. The papers presented at the annual meeting are peer-reviewed, and a portion of them are published in the Transportation Research Record.

TRB also maintains standing committees that provide direction to the research field and assist in disseminating research findings. Committees such as Transportation Safety Management, Highway Safety Performance, Pedestrians, Occupant Protection, and many others specifically address topics related to road safety. TRB manages the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP), described below.

State Research Sponsors

American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO)

Other Research Sponsors

Although the majority of road safety research is funded by government sources, private companies and organizations also participate in funding road safety research. Prominent examples of these are the IIHS and the American Automobile Association Foundation for Traffic Safety.

AASHTO is the organization behind NCHRP. The NCHRP funds many road safety research projects each year on a variety of topics that are integral to the State departments of transportation (DOTs) and transportation professionals at all levels of government and the private sector. The NCHRP is administered by the Transportation Research Board (TRB) and sponsored by individual State departments of transportation. The research projects are conducted in cooperation with FHWA (FHWA). Individual projects are conducted by contractors with oversight provided by volunteer panels of expert stakeholders. NCHRP projects cover a wide range of highway topics, but there is a specific focus area for safety.40 AASHTO also maintains several committees that oversee road safety topics including the Standing Committee on Highway Traffic Safety and the Subcommittee on Safety Management. These groups decide which research topics should be prioritized for funding under NCHRP.

State Research Programs

In addition to participating in large scale research efforts, such as NCHRP, State departments of transportation often fund road safety research projects on topics that are of particular interest to their State. They use portions from Federal funds that are specially designated for research projects. Every State has a different process for how the research projects are conceived and conducted, but a common arrangement is that the State DOT contracts with universities in the State to conduct the research. The research topics typically pertain to current road safety issues that are high priority within the State or issues related to geography, terrain, weather, driver population, or other such factors that may be particular to that State. For example, a State in a snowy climate may sponsor a research project on how snowplowing affects the visibility and durability of inpavement reflective markers.

Chapter 15 - Strategic Communications

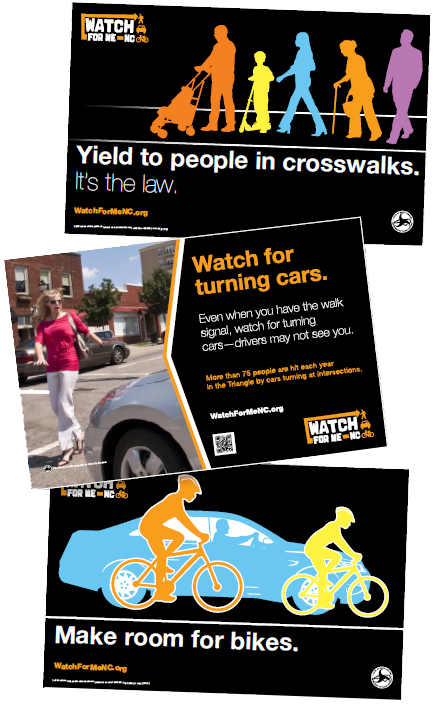

Public education campaigns like this one are commonly used to improve road user attitudes and awareness. (Source: NHTSA)

A key part of many efforts to improve road safety is sharing safety messages through strategic communications. This chapter provides an outline of the most basic elements of strategic communications that transportation safety professionals should use when working with their communications teams to craft and disseminate messages that seek to improve traffic safety culture. As mentioned in unit 1, strategic communications programs like public education campaigns are commonly used to improve road user attitudes and awareness.

A strategic communications program involves elements of communications, marketing, and public outreach. These components often overlap and are not easily separated into distinct categories with unique functions. Strategic communications is more than the sum of its parts. Rather, it is a structured methodology that fuses messaging with marketing while garnering public support.

Several examples demonstrate that strategic communications can result in behavioral changes. An effort in the late 1980s to stop impaired driving resulted in substantial decreases in Driving Under the Influence (DUI) citations. NHTSA saw successful results from the implementation of the “Buckle Up America Campaign” and the National Safety Council’s “Airbag and Seat Belt Safety Campaign” and the high-visibility public information program “Click It or Ticket” safety belt enforcement campaign. Strategic communications was a key element of all of these efforts.

Other examples of communicationsefforts include:

- Campaigns with careful pre-testing and delineation of a target group that receives the messages.

- Longer-term programs that deliver a message in sufficient intensity over time.

- Education programs built around behavioral change models, using interactive methods to teach skills to resist social influences through role playing.

- Public information campaigns that accompany other ongoing prevention activities.

- Programs conducted as part of a broader community effort or in support of law enforcement.

An effective strategic communications program, like any effective endeavor, needs a plan. The following are key steps in developing a strategic communications plan that every road safety professional should know:

- Develop objectives

- Identify target audience

- Design messaging

- Select communications channels

- Determine budget and resources

- Measure results

Each step of this communications plan outline is discussed in the sections below.

1. Develop Objectives

The first phase in creating a strategic communications plan is to determine objectives. A welldesigned communications strategy may achieve multiple goals, such as informing the public about transportation safety issues, educating key political leaders on their roles in saving lives, and encouraging active participation from safety partners.

To develop objectives, safety professionals must start by defining what “success” should look like. Important questions include:

- What are we trying to achieve?

- Do we want people to take a new action, or do we want people to modify an old behavior?

- How do we know when we have achieved our goal (i.e., what are our target metrics)?

Establishing measurable goals is an important piece that should be not be overlooked. Having a target or measurable goal (metric) makes it simpler to gauge the success of a campaign.

2. Identify Target Audience

After developing communications objectives, the next step is deciding what populations to target. For example, safety professionals must decide if the program should be aimed at the general public or a specific sub-set of the population, such as young drivers, pedestrians, or people who drive aggressively. A message could also be aimed at road safety professionals and government officials. In addition to a target audience or audiences, secondary audiences may be included. For instance, if the program targets young drivers, a secondary audience may include the parents of these novice drivers.

3. Design Messaging

Watch for Me NC

(Source: Watch for Me NC)

Watch for Me NC is a comprehensive program run by the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) in partnership with local communities. It is aimed at reducing the number of pedestrians and bicyclists crashes.

The Watch for Me NC program involves two key elements: 1) safety and educational messages directed toward drivers, pedestrians, and bicyclists, and 2) enforcement efforts by area police to crack down on some of the violations of traffic safety laws. Local programs are typically led by municipal, county, or regional government staff with the involvement of many others including pedestrian and bicycle advocates, city planners, law enforcement agencies, engineers, public health professionals, elected officials, school administrators and others.

All North Carolina communities are encouraged to use Watch for Me NC campaign materials to improve pedestrian and bicyclist safety in their communities.

Once safety professionals identify the target audience, they must determine what the message will be. A key step is to define the problem that needs to be solved in order to craft the message. Messaging should be designed so that it encourages specific actions, so draw on established objectives to determine what those actions should be. Designing the message will bring about questions like these: “Is the intended action a change in safety funding or policies? Or is the goal a change in user behavior?” Focusing efforts on strategies that connect with the target audience is particularly important in today's environment of tight budgets and scarce resources.

After message development, safety professionals should consider pre-testing the message with the target audience. A pre-test can identify points of view of the target audience, provide unexpected insights or reactions that can help further refine messaging, and help determine if the communications plan will improve the chance of accomplishing the stated objectives.

4. Select Communications Channels

Carefully crafted messages need to be conveyed through appropriate channels in order to be effective. Communications channels include the personal and the non-personal. Personal channels include the advocate channel (advocates championing the objectives of a campaign), expert channel (independent experts making statements to the target audience), and social channel (word of mouth communications). Non-personal channels include media, events, and public outreach—examples of common non-personal dissemination techniques include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Brochures

- Conferences/workshops

- Dynamic message signs

- Media advisories

- New media (e.g., blogs, podcasts, Facebook pages)

- News media events

- Newsletters and press releases

- Public service announcements

- Print, radio, and television advertising

- Social media

- Websites

Safety professionals must work with the communications team to determine the right media mix, which is the combination of communication channels needed to meet communications objectives. Together they must figure out which channels—personal and/or non-personnel—and which tactics will help meet the stated road safety goals. For example, personal channels may work well with government officials, while non-personnel channels may work best with reaching out to the public. Also, a detailed timeline of channels and tactics to employ, is crucial for implementing a strategic communications plan.

5. Determine Budget and Resources

Implementing a comprehensive communications program requires resources like money, staff, and time. Therefore, developing a budget for the program is an integral part of carrying out the plan. Safety professionals should consider every element of the proposed plan, and make sure there are resources to cover them all. For instance, it may be necessary to hire an outside firm to help develop and refine messages and tactics, and that should be factored into the budget. All program expenses should be tracked to determine how well the budget has been met when measuring results.

6. Measure Results

Evaluation of a strategic communications program is essential. Without evaluation, current programs may waste resources and fail to contribute to a road safety program's goals. Evaluations help safety professionals learn from outcomes and help them allocate funds in the most efficient manner. If a program does not meet expected metrics, they should reexamine the program and/or move the resources to other efforts.

To measure the results of the program, safety professionals must go back to the objectives and predetermined measurable goals and targets. The original questions in Step 1 will guide the evaluation of the success of the program. Surveys, focus groups, and/or one-on-one interviews are often good ways of measuring the performance of a strategic communications program.

As far as data allow, safety professionals should also attempt to compare the effectiveness of communication campaigns in the same way that they compare the performance of traditional infrastructure countermeasures. The comparison will help identify campaigns that are both effective and efficient.

Chapter 16 - Advancing Road Safety

This chapter covers the crucial role that safety leaders, champions, and coalitions play in road safety management. While the various agencies and organizations involved in road safety bring unique and valuable perspectives to the problem of road safety, they also bring competing philosophies and problem-solving approaches. Bringing these various entities together to develop and implement an effective road safety program is a challenge.

The major topics include:

- Leaders

- Champions

- Coalitions

Leaders

Leadership is essential in any field, but it is particularly important in road safety for three major reasons:

- The safety field is diverse. It draws on the skills of educators, politicians, advocates, bureaucrats, public servants, and others. These groups sometimes work in harmony, but too often, they work in isolation. Leaders are necessary for cohesion in a complex, multi-stakeholder environment.

- A great deal of technical knowledge is available in the safety field regarding the most effective means of addressing the contributing factors to crashes. However, technical knowledge is not sufficient for change to occur. Leadership is necessary to ensure technical knowledge is used.

- Road safety programs and projects compete with other public sector priorities. Without strong leaders to support the safety cause, public sector decision makers might not consider or prioritize safety.

Leaders bring people together, provide essential direction, and motivate people.

Leadership Activities

Leaders are an instrumental part of any planning process, and road safety programs are no exception. Leaders bring people together, provide essential direction, and motivate people to participate in and implement the program. Leaders should be engaged and actively involved in the process.

Consider a few examples of leadership in safety:

- State DOT leaders decide that reducing fatal and serious crashes should be the first priority of the department. They garner staff support to make funding and structural changes to the organization to support the shift in priorities.

- Law enforcement officers develop new incentive programs to encourage officers to identify and arrest impaired drivers. They successfully sell the program to their managers.

- A trauma nurse initiates a “teachable moments” campaign in which nurses teach patients about the risks associated with drinking and driving.

- A mayor recognizes that many streets in her city are not suitable for safe travel by pedestrians and garners support and funding from the city council to build sidewalks and improve the safety of transit stops.

In each of these examples, the leaders recognized a need for change, acted on the need, and inspired others to follow. Anyone with drive, dedication, and a good idea can lead.

Leadership Traits and Skills

Good leaders influence policy direction, set priorities, and define performance expectations. They energize the road safety process and see to it that a plan is developed, and once developed, is implemented. They are risk takers, problems solvers, and creative thinkers committed to doing what is necessary to advance the cause, which sometimes means breaking traditional institutional barriers and balancing competing agency priorities.

Leaders are often known as program managers, and their activities keep the implementation process on track. They manage the process and attend to the day-to-day tasks of arranging, facilitating, and documenting meetings, tracking progress, and moving discrete activities through to completion.

Leaders are needed throughout all stages of road safety development, implementation, and evaluation. They communicate the safety vision and support a collaborative framework that enables safety stakeholders to participate actively in implementation.

Leadership Development

To expand leadership support, begin with the safety partners already committed to the safety concept and process. Encourage the leadership of those partners to contact their peers, explain the significance of their efforts, and marshal support. Their endorsement of the safety vision should include encouraging staff to stay engaged and building relationships across organizational boundaries and traditional areas of responsibility.

Leadership support affects agencies or organizations internally by granting permission to dedicate time and resources to the safety effort. It also holds those responsible for safety accountable. Leadership should recognize that this is an ongoing process and institutionalize the change in the safety decisionmaking culture.

The safety program manager may perform either as a part- or full-time permanent role; experience demonstrates a dedicated role is preferable.

Champions

Successful road safety programs call for at least one champion to assist in gathering all critical safety partners into a collaborative group. Champions provide enthusiasm and support for the safety programs.

Like leaders, champions must be credible and accountable, have excellent interpersonal and organizational skills, and be skilled expediters.

Champion Activities

Safety champions help secure the necessary leadership, resources, visibility, support, and commitment of all partners. Sometimes the DOT leadership, or the leadership of the primary sponsoring agency, appoints the champion. A safety champion can reside at any level within the organizational structure and can perform various functions.

For example, a safety champion may lead the executive committee that meets periodically to solve problems, remove barriers, track progress, and recommend further action. The role of the executive committee is to decide which projects or strategies are funded based on input from the emphasis area teams, and to prioritize them based on benefit/cost analysis, expected fatality reductions, and the extent to which they address the project's goals and objectives.

Where relationships are not fully developed, the champion may have to put in additional effort to keep the full range of safety partners committed and actively participating.

Champion Traits and Skills

FHWA published the “Strategic Highway Safety Plan Implementation Process Model” that identifies two types of transportation safety champions.41 The first have access to resources and the ability to implement change. In other words, they may not be involved in the day-today management responsibility for program development and implementation, but they are able to “move mountains” in terms of resource allocation and policy support. The second are leaders who inspire others to follow their direction. These champions are people who provide enthusiasm and support to transportation project implementation. They tend to be subject matter experts and highly respected within their own agencies and in the safety community.

Succession Planning

All agencies and organizations undergo staff changes, and it is essential to train the leaders of tomorrow to ensure that the focus on safety continues into the future. This can be accomplished by assigning leadership responsibilities for program implementation to newer staff and by ensuring that all staff have opportunities to engage and lead during meetings and other activities.

To ensure continuity when an individual champion or leader retires, takes a position in another organization, or moves out of State, a systematic approach to identifying their replacement is necessary. The selection process should be based on individual skills, leadership traits, and the position held within a stakeholder organization. One way to institutionalize the selection of safety committee members is to link their selection to the position they hold within the stakeholder organization. For example, whoever assumes the previous safety champion or committee member's position should also become the new committee member.

Coalitions

Safety partners and organizations bring unique and valuable perspectives to bear on the transportation safety problem. However, differing philosophies, competing priorities, and varying business cultures may make collaboration a challenge. Coalitions are an opportunity for road safety leaders and champions to bring together the various disciplines and agencies and focus on the shared goal of reducing crashes. Whether coalitions are short-term, long-term, or permanent, they offer road safety collaborators the prospect of solving complex issues through partnerships.

Safety Partners

The organizational structure of agencies and interagency working relationships are important factors to consider when bringing safety partners together. Rather than create entirely new committees, a champion should build upon existing relationships, interagency working groups, and committees.

Many States have functioning transportation safety committees, such as a TRCC, an Executive Committee for Highway Safety, or a Towards Zero Deaths (TZD) coalition. Regardless of how safety partners are brought together and organized to contribute to the safety process, champions should look for ways to expand membership to include a broad range of partners, such as insurance, trucking and motor coach companies, fire and rescue, local businesses, and others.

When States implement the Federally required SHSPs, their safety partners typically include those that are Federally required, such as EMS providers, health and education departments, Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program (MCSAP) managers, local agencies, tribal governments, special interest groups (e.g., MADD), and others.

With an emphasis on wide-ranging collaboration that includes many external partners, it can be easy to overlook the importance of broad DOT involvement, as well. Early involvement of planning, design, operations, and maintenance will enhance the implementation of safety strategies, especially if they are new or experimental.

Some champions bring partners together by convening a safety summit or meeting. This could be a large initial kickoff meeting or a meeting of the safety working group or steering committee. It provides an opportunity to learn about each of the safety partner priorities and understand what they contribute. Coalitions should give participants the opportunity to describe their safety concerns and current programs. This may advance the discussion of critical safety issues, identify opportunities, and forge an agreement on how to proceed.

Benefits of Collaboration

Engineering, planning, emergency response, and behavioral approaches all have roles to play in addressing road safety. Professionals in these various disciplines have different skill sets, and they approach solutions using different methods. Dramatic improvements in roadway safety are more likely to result through a combination of techniques than from techniques from a single discipline. This need for multidisciplinary solutions necessitates collaboration.

Unit Summary

Improving road safety is a complex endeavor requiring the knowledge and expertise of a wide range of professionals. Road safety improvement is a joint effort across many Federal, State, and local agencies, each with their own particular focus area.

Federal agencies often play a role in providing funding and national cooperation for focused road safety efforts. State and local agencies implement road safety improvements, either for roads and intersections in their jurisdiction, or on the road users themselves. The efforts of these government agencies is supported by a broad base of road safety research, which provides knowledge on identifying safety problems or evaluating potential solutions. Strategic communications allow all road safety partners to be effective in their efforts to improve road safety, either in communicating to the public or to transportation professionals.

Leadership is essential in the road safety field. The diversity of the field, the importance of coordination among disciplines, and the need to defend safety programs among a host of competing public sector priorities all contribute to the need for strong leadership. Successfully implementing road safety efforts relies on safety champions and coalitions that bring together safety partners from all agencies and disciplines.

EXERCISES