This section summarizes the investigation findings into major practice areas associated with prioritization practices. The practices outlined in this section highlight programs in certain States to implement five general practice areas. The programs listed represent a sample of all activities undertaken by States and may not fully describe the detailed processes undertaken by the example States in implementing these practices. The purpose is to give a brief summary of how individual States have innovated within each area.

This information was compiled from a number of sources:

- Interviews with selected State highway-railway crossing administrators.

- Review of State action plans (SAP) submitted under the Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (RSIA08).

- Review of annual highway-railway grade crossing reports submitted under the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP).

- Supplemental information provided in interviews.

- Previous Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) highway-railway grade crossing reports to Congress.

Appendix A summarizes information for this section, including contact information for more information about State highway-railway grade crossing programs.

PRACTICE 1 – STATES ARE TAILORING RISK FORMULAS TO STATE NEEDS

Overview

There is no one-size-fits-all risk formula that is used by all States, although several common elements are used by many States. Some States have adjusted weighting factors and constants to reflect State experience. Others have internal programs for different purposes, each with a specific project selection process/formula. One State uses the Federal Railroad Administration's (FRA) GradeDec.net as a what-if simulator to evaluate corridors under changing rail traffic profiles or economic development prospects.

Additionally, some States use railroad-supplied information on near misses at crossings as part of the evaluation/risk assessment process. Other States connect State crash records with inventories to obtain more potential causal information on crossing-related crashes. Some States evaluate categories of crossings separately–passive against passive, active against active, and gates/lights against similar crossings. Even so, some States are responding to special external issues through highway-railway grade crossing programs, focusing on passenger routes with passive crossings or rail lines carrying crude oil trains.

Example Practices

New Jersey

New Jersey focuses its efforts on those crossings located along corridors with crude oil trains. New Jersey also focuses on improving crossings with 8-inch incandescent lights to upgrade these warning signals to 12-inch light-emitting diodes (LEDs).2 Since most of the State's identified issues at the local level relate to crossing surface conditions, New Jersey is creating a listing of those crossings with surface condition issues noted within its inspection process for renewal.

Ohio

Ohio has four major grade crossing programs that use a combination of both Federal and State funds. The use of four separate programs allows for flexibility to maximize needed improvements at the State's at-grade crossings. The four programs are as follows:

- The formula-based upgrade program is based on a calculation of the most hazardous crossings.

- The corridor-based upgrade program provides a framework for systematically considering, identifying, and prioritizing projects that have public safety benefits at multiple grade crossings along a railroad corridor. Ohio identifies these corridors in collaboration with the railroads. The Heartland Corridor is an example of a corridor-based project that runs through the State.

- The constituent-identified upgrade program considers project referrals from a number of sources and makes selections based on hazard rankings, extenuating conditions, and funding availability.

- The preemption program upgrades warning devices and traffic signals to establish appropriate traffic signal preemption when a train approaches a crossing that has a highway traffic signal in close proximity.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania's project prioritization process uses the FRA's GradeDec.net tool to compare safety differences if physical infrastructure or traffic (rail and highway) conditions change, which could include new customers along rail lines, track speed changes, and train traffic level adjustments. This tool allows for adjustments to items such as train traffic distribution throughout the day, when trucks or other vehicles arrive, and when heavy transit or bus traffic happens.

PRACTICE 2 – STATES ARE INCORPORATING BENEFIT-COST EVALUATIONS INTO PROJECT SELECTION

Overview

A number of States build benefit-cost analysis (BCA) into their project evaluation processes to varying degrees. Some states are using BCAs more comprehensively, integrating the practice department wide in order to build in consideration and monetization of indirect costs for highways (e.g., delay, rerouting, logistics, and road closure time) and railroads (e.g., passenger and freight delays, lack of alternative routes, logistics needs delayed, track closure time, and dispatch chaos). Other States include BCAs in order to rank specific safety improvement projects.

Example Practices

California

California includes a cost-benefit factor as part of the final ranking process. This measure is specifically applied during the second phase of its defined project selection methodology.

North Carolina

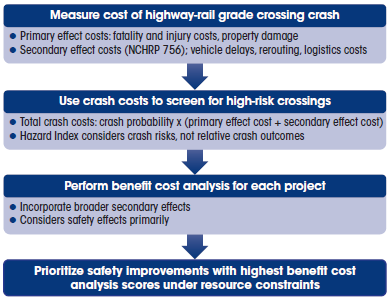

North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) is currently transitioning to using benefit-cost evaluations within its existing prioritization methodology as part of an agency-wide effort, as explained in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Diagram. North Carolina benefit-cost analysis methodology for highway-railway crossing safety programs.

Source: NCDOT

NCDOT's Rail Division has contracted with a consultant to develop a benefit-cost calculation that takes into account both direct and indirect costs and benefits. This approach is scalable and adaptable, allowing NCDOT to incorporate items not currently considered in grade crossing project selection. Also, this process allows for a BCA similar to roadway improvements in the State, which will permit future grade crossing safety projects to be evaluated alongside and compete with all traffic safety projects including in additional State funding categories.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin directly uses a BCA calculation within its project selection process. Wisconsin analyzes statewide crossing improvement needs using BCA methods to evaluate a data set extracted from the Wisconsin DOT Rail Crossing Data Base. The procedure follows the USDOT Accident Protection and Severity formulas and is used to develop upgrade priority groups, which are then further reviewed using additional procedures such as BCA.

PRACTICE 3 – STATES ARE SUPPLEMENTING FEDERAL SECTION 130 HIGHWAY- RAILWAY CROSSING PROGRAM FUNDING WITH STATE DOLLARS

Overview

Some States have special funding set-asides for highway-railway crossing protection and roadway improvements that have been established by their respective State legislatures. Other States are using flexible State and Federal HSIP funding for crossings. Many of the State-based funds of this type are used for projects not eligible for Section 130 (e.g., pavement treatments at grade crossings) or bundling of State and Federal funds to complete grade separations.

Example Practices

Illinois

Illinois supplements the State's Section 130 program funding with State funds from gas tax revenues to support its Grade Crossing Protection Fund. These monies assist with funding grade crossing improvement projects along local Illinois roadways, whereas State roadways are addressed using Federal funds. Created in 1955, the Grade Crossing Protection Fund is administered by the Illinois Commerce Commission and funds improvements such as:

- Signal system upgrade or replacement.

- Crossing closures.

- Bridges (i.e., replacement/new structure).

- Pedestrian grade separations.

- Interconnect projects.

- Funding to local agencies for highway approach grading.

- Construction of connecting roads for closing projects.

- Remote monitoring systems for railroad companies.

- Renewing crossing surfaces.

Nebraska

Nebraska State statutes provide for a financial incentive to local road authorities that agree to the elimination of a highway-railway crossing by closing the crossing or rerouting the roadway. It does this by providing $5,000 from the State Grade Crossing Protection Fund and $5,000 from the railroad involved. The local road authority also receives actual costs associated with the closure, up to a cap of $12,000. These costs cover such things as barricades and the removal of the approach roadway. In addition, a State fund collected from fuel taxes can be used for crossing surfacing, with local matching funds required.

Nebraska also has a special State fund specifically for highway-railway grade separations, funded through a train mile tax. In addition, some HSIP dollars are moved into grade separation projects, given the scale of such projects. All grade separations in the State require two crossing closures, the one being replaced and another one nearby.

Texas

Texas supplements the Federal Section 130 program by administering additional programs. The State Replanking Program replaces crossing surfaces on the State highway system. TxDOT also provides funding to railroads for crossing signal maintenance through the Railroad Signal Maintenance Payment Program and allocates State funding for grade separations.

PRACTICE 4 – STATES ARE INVESTING PLANNING DOLLARS (2 PERCENT ALLOWANCE) IN INVENTORY IMPROVEMENTS

Overview

States are using inventory systems and specialized modules from consultants and vendors to expand management capabilities and tailor systems to State needs. They are expanding the reach of GIS capabilities to inventory systems and also including photos. Some States use inventory systems to create asset-management-like systems for crossing improvements and diagnostics. The States use a variety of consultants, in-house staff, or student interns to keep inventory data up to date.

Example Practices

California

California is utilizing the 2 percent allowance on a major grade crossing inventory update for the entire State. The multiyear project is split into multiple completion phases, with the first phase consisting of passive crossings and subsequent project years updating active crossings.

Oklahoma, Nebraska, and North Carolina

Oklahoma, Nebraska, and North Carolina are examples of other States using the 2 percent allowance for inventory improvements, with Nebraska maintaining a consultant under contract to provide continuing maintenance of its web-based railroad inventory management system.

Texas

The new database program in Texas, the Texas Railroad Information Management System (TRIMS), was placed into service in March 2013. Since that time, several enhancements have been made to the program to expand its functionality. Scheduled periodic updates of train and highway traffic levels by staff and consultants are an example of the types of inventory data that TRIMS maintains.

PRACTICE 5 – STATES ARE APPLYING INNOVATIVE IMPROVEMENTS TO PROJECT EXECUTION

Overview

States are working directly with railroads to identify projects and improve project execution. In the case of most complicated pre-emption projects, States could benefit from better railroad appreciation and understanding of the highway traffic engineering processes required for implementation. Similarly, highway agencies would benefit from understanding the needs and requirements of railroad companies in the construction of combined projects. (A proposed process for highway agency–railroad company cooperation was outlined in the recent Strategic Highway Research Program 2 report R16-RR-1, Strategies for Improving the Project Agreement Process between Highway Agencies and Railroads.)

Many States depend on FHWA division office safety staff to understand the unique issues about the projects associated with Section 130 program funding. FHWA division staff often make the difference in getting Federal funds authorized on a timely basis. The following examples highlight several innovative ways in which States have improved project execution.

Example Practices

California

California recognized that the contracted local agency and railroad do not always coordinate their efforts to implement the construction aspects of the project. This led to confusion between the agencies and frequent project delays. To better facilitate the project's implementation, the California DOT and the California Public Utilities Commission are now coordinating a joint project kick-off teleconference once the contracts have been executed to ensure that expectations are understood and lines of communication are established.

New Jersey

New Jersey maintains a master agreement with every railroad operating in the State. This expedites the project execution process by developing each project as a task/change order within the standing agreement. The State's annual report also highlights the positive relationship with the local FHWA staff member, who thoroughly understands rail safety, resulting in improvements to the FHWA review process.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania administers a State-level short-line railroad development program through Pennsylvania DOT district personnel. The same personnel are directly involved in grade crossing safety prioritization decisions. Their activities with short-line economic development processes and stakeholders give them detailed knowledge of unique rail operational needs, specific circumstances, or needs that may be in play at candidate funding locations. The assignment of knowledgeable staff across these varied functions improves the overall selection process.

OTHER ISSUES OF NOTE

North Carolina is working to connect grade crossing inventory information into the North Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles oversize/overweight permitting systems for trucks as well as to include railroad contact information if crossings become blocked. In March 2015, an Amtrak train crashed into an oversized load that was blocking a grade crossing while attempting a turn onto an adjacent highway. The load was being escorted, but the trucking company did not anticipate the narrow turning radius complicated by the grade crossing, and the company and its escort vehicles did not communicate its position to the railroad responsible for the grade crossing.

While the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) and the FAST Act are causing more departments of transportation to use performance measurements, applicable performance measurement tools for the highway-railway grade crossing program remain hard to come by:

- HSIP reporting on before-and-after behavior can be misleading, given the infrequency of crashes and crashes that are not the result of crossing conditions (e.g., suicides).

- Some States measure program activity–inspections, diagnostic reviews, and crossing projects completed–instead of results.

2 Section 4D.07 of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices requires 12-inch signals on all new signal faces. [ Return to note 2. ]