Original publication: N/A

Key Accomplishments

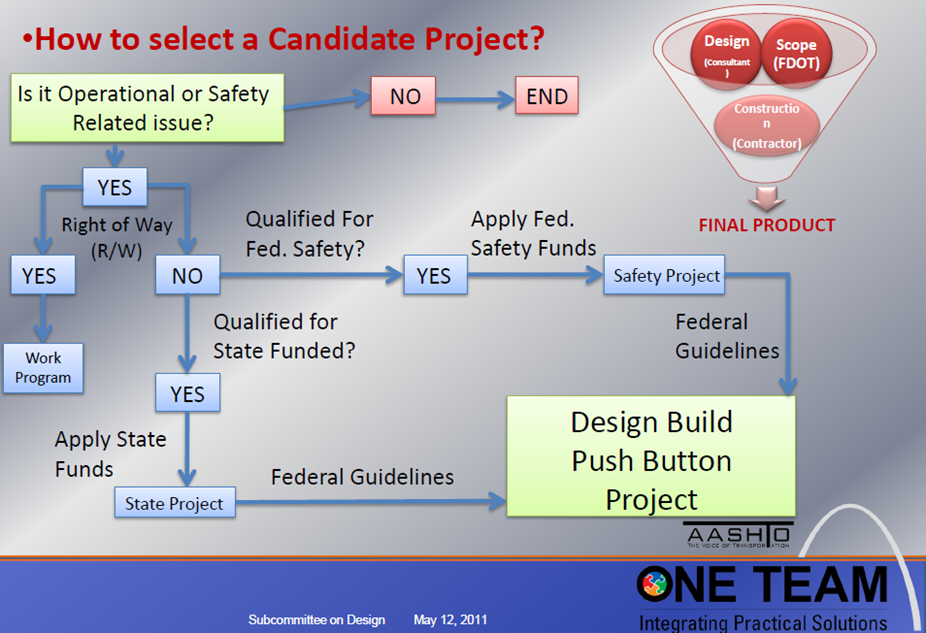

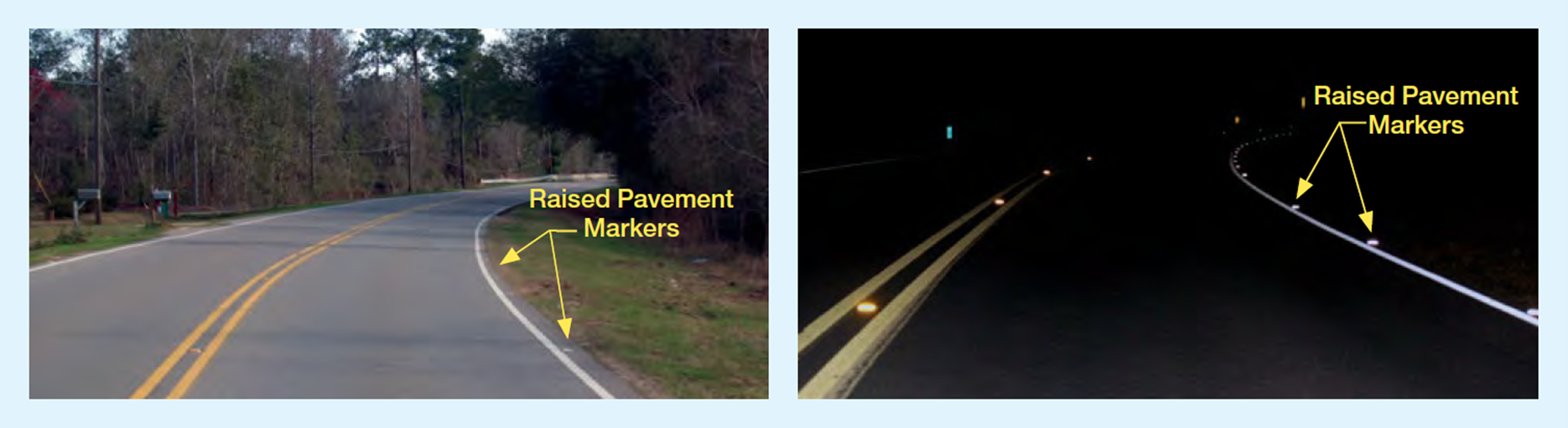

The South Carolina Department of Transportation (SCDOT) began identifying safety improvements to be deployed systematically at intersections across the State in 2008 as part of the Federal Highway Administration's (FHWA) Office of Safety Intersection Focus State initiative. SCDOT believed these improvements would reduce the number of intersection-related fatalities and serious injuries, which was one of the goals defined in SCDOT's 2007 Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP). As part of this process, SCDOT used a 5-year analysis of statewide crash data to identify high-crash intersections and recommend improvements—primarily signing, pavement markings, and signal enhancements. Based on these findings, a list of 2,204 intersections was compiled in the South Carolina Intersection Safety Implementation Plan (ISIP), and SCDOT sought a contracting mechanism to implement the recommended improvements identified in the ISIP within a three-year time frame.

Following the identification of intersections where countermeasures would be applied, SCDOT developed a unique contract vehicle structured to accommodate the systematic approach proposed in the ISIP. The contract was a single, statewide, three-year contract, renewable each year, which allowed for adjustments to be made to improve the quality of the work in subsequent years. The contract was structured to treat approximately one-third of the intersections identified in the plan each year for 3 years.

Throughout the project, the selected contractor and the subcontractor developed a Field Installation Work Book that contained all pertinent information on installation at a particular site, including final approved drawings, installation checklists, and punch list forms. In addition, the contractor and subcontractor developed a reconciliation spreadsheet to manage multiple crews and to document and verify installed quantities for payment during the course of the fast-paced project. The contractor and subcontractor also used a project management website to provide changes to intersection plans to SCDOT on a regular basis and report on the progress of work performed. The contract defined the minimum requirements of the website; however, the website developed ultimately included additional functionality.

Because 23 USC 120(c) allows certain safety improvements such as signing and pavement markings to be eligible for Federal funding, the project was entirely federally funded. The consistency between South Carolina's ISIP and SHSP and the identification of the projects through a systematic, data-driven process allowed for the projects to be implemented using Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) funds.

Through this project, SCDOT made improvements to more than 2,200 intersections that account for forty four percent of all intersection crashes in South Carolina. In deploying this project, SCDOT employed a statewide, low-bid contract vehicle that allowed for uniform implementation resulted in administrative efficiencies and economies of scale through decreased per-unit prices on bulk purchases.

Results

The project has been successful in terms of its outputs and short timeframe, addressing over 2,200 high-crash-frequency intersections in three years. FHWA plans to evaluate the safety effects of SCDOT's low-cost systematic intersection improvements as part of its Evaluation of Low cost Safety Improvements Pooled Fund Study.

Contact

Joey Riddle

South Carolina DOT

Safety Program Engineer

(803) 737-3582

RiddleJD@dot.state.sc.us

Daniel Hinton

FHWA South Carolina Division

Safety and Operations Engineer

(803) 253-3887

Daniel.Hinton@dot.gov