Tribal SHSP Involvement in North Dakota Leads to Continuous Efforts to Improve Tribal Road Safety

The North Dakota practice is discussed after the following introduction about Tribal Government Involvement in the Strategic Highway Safety Plan process.

Other states in this SHSP/Tribal Government Noteworthy Practices series: MT, SD, WA

Involving Tribal Governments in the Strategic Highway Safety Plan Update Process - Approaches and Benefits

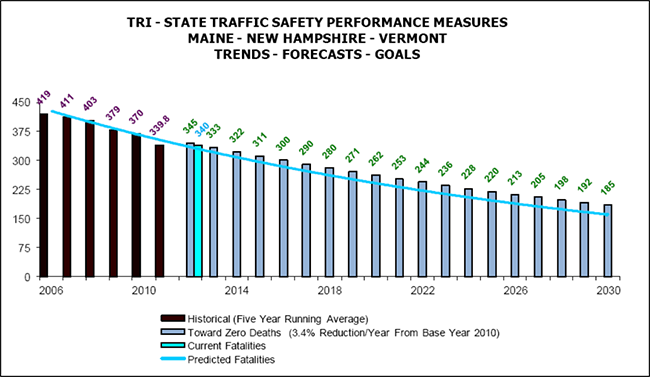

As States move toward achieving zero deaths on their roadways, the impact of motor vehicle crashes in tribal communities and on tribal roads cannot be overlooked. American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations experience higher rates of fatalities associated with transportation than does the population as a whole. Crashes are also the leading cause of unintentional death for AI/AN ages 1-44.

Legislation requires that the SHSP is developed in consultation with major Federal, State, tribal, and local safety stakeholders (23 U.S.C.148 (a)(12)(A)). SHSPs must also consider safety needs of, and high-fatality segments of, all public roads, including non-State-owned public roads and roads on tribal land (23 U.S.C.148 (a)(12) (D)).

States and tribal governments are working together in an effort to reduce roadway injuries and fatalities in tribal communities. This includes collaborating during the State Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) process, an effort that brings together a diverse group of stakeholders to identify critical roadway safety challenges and establish potential solutions. Tribes are also developing Strategic Transportation Safety Plans of their own, which may allow access to additional resources such as the Tribal Transportation Program Safety Fund.

These noteworthy practices highlight the activities of four States and tribal communities to collaborate during and after the SHSP process. They contain several recurring themes:

- Establishing a government-to-government relationship between State offices and tribal governments is very effective because it establishes respectful lines of communication and agreed-upon approaches that facilitates discussion on roadway safety issues.

- Tribal involvement in the SHSP process insures tribal concerns and strategies are addressed in the SHSP.

- Tribal safety summits are an effective platform for information-sharing among tribes on roadway safety issues and often strengthen inter-tribal relationships.

- An established network for communicating between tribes and State agencies leads to better project coordination and delivery, lower project costs, stronger relationships, and better information sharing.

North Dakota

Background

Continuous communication and collaboration between tribes and the North Dakota Department of Transportation (NDDOT) has led to Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) updates that account for unique tribal needs, and to ongoing road safety improvement projects on tribal lands.

The overarching goal of tribal involvement in SHSP updates is to reduce fatal crashes across the State. Many fatal crashes among tribal members are alcohol-involved or include drivers or passengers not wearing their seatbelts—statistics show the same is true Statewide.

While the underlying problems related to fatal crashes are consistent across the State, North Dakota tribal members are disproportionately represented in road fatalities. Tribal populations account for about 5 percent of the State population but 15 to 20 percent of vehicle crash fatalities. To reduce Statewide fatal crashes NDDOT knows it is imperative to reduce fatal crashes among tribal populations.

Building off of longstanding relationships between NDDOT liaisons and tribal representatives, NDDOT began its most recent comprehensive SHSP update in 2012, with its final plan released in fall 2013. There were 75 to 100 stakeholders involved in updating the SHSP, including an SHSP Steering Committee including the director of the North Dakota Indian Affairs Commission and representatives from each of the 4 tribes in North Dakota.

Tribal Involvement in the Strategic Highway Safety Plan

Because North Dakota is a State with a small population and a prominent tribal culture, NDDOT for decades, has collaborated on road safety with tribal representatives. The established relationships between tribes and NDDOT made it relatively easy to incorporate tribal needs into the 2013 SHSP update. The SHSP Steering Committee had oversight over the update process and included about 20 stakeholders, including tribal representatives and representatives across the 4Es—engineering, education, enforcement, and emergency medical services (EMS).

Local Road Safety Program: An SHSP Extension

About half of severe crashes (fatal and incapacitating injury crashes) in North Dakota happen on local roads, and the Local Road Safety Program (LRSP) is NDDOT's continuous effort to reduce severe crashes on those roads. The LRSP grew out of collaboration with a variety of stakeholders to update the SHSP, and today covers 53 counties, 12 cities, 4 tribes, and 1 national park.

Over the past two-and-a-half years, each of those entities has developed a prioritized list of road safety projects. The NDDOT provides half of its Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) federal funding toward those projects and leads a solicitation and evaluation process—to ensure data-driven projects that best address identified safety issues. Projects tend toward low-cost effective infrastructure improvements, such as edge lines, rumble strips, chevrons, destination lighting, and enhanced signing.

In forming the LRSP, NDDOT staff met with all four tribes in North Dakota separately from county and city stakeholders. NDDOT staff took this approach so that particular tribal needs would be sure to be reflected in selected projects.

For behavior-based strategies that complement LRSP projects—for example, promoting seat belt use—NDDOT relies on tribal traffic safety outreach coordinators (funded by the NDDOT through grant funds received by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [NHTSA) to conduct community-level outreach through local events and activities and to partner with a media firm to create tribal-specific educational material for distribution through outreach activities.

Finally, the LSRP has helped guide tribes in the development of their transportation safety plans. For instance, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians has used the process of creating its local road safety plan to inform and complete its federally required strategic transportation plan.

Key Challenges

There is some variation in the level of tribal participation in LRSP and project execution. One tribe has a consultant who handles paperwork, significantly reducing the time to propose and plan projects.

Data quality is another challenge in reaching SHSP and LRSP goals. Only one out of the four tribes in North Dakota has equipment compatible with the State's electronic crash reporting system, and that tribe is not yet submitting electronic crash reports to the system. A simple but cumbersome solution is to have two laptops in tribal law enforcement vehicles, with each laptop respectively linked to tribal and State crash reporting systems. This solution has been met with resistance due to equipment costs and the extra work involved in entering crash data twice.

Benefits to Tribal Participation in SHSP and LRSP

- Ensures that NDDOT is aware of concerns on reservations, especially regarding State-owned roads that go through tribal land.

- Ongoing coordination and collaboration is a success that begets success. Years of outreach leads to SHSP updates that include strategies to reduce crashes on tribal lands and across the State, and there are now full-time Traffic Safety Outreach Program Coordinators (funded through NHTSA grant funds) that serve as points of contact on two of the State's reservations.

- Low cost systematic projects for implementation identified through a data-driven process.

- A simplified application process for Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) funds.

See these other SHSP/Tribal Involvement Noteworthy Practices:

Contact

Karin Mongeon

Safety Division Director

North Dakota Department of Transportation

(701) 328-4434

KaMongeon@nd.gov