GM's Better Highways Award

The increasing need for highway improvement prompted the General Motors (GM) Corporation to announce, on November 20, 1952, a Better Highway Award for the best essay on "How to plan and pay for the safe and adequate highways we need." Prize money totaled $194,000 for 161 awards, with the grand prize being $25,000. Anyone, including GM employees, could submit an entry except the panel of judges and their families. If a GM employee's essay was a winner, a duplicate award would be made to keep the amount for outsiders intact. The judges were:

- Ned H. Dearborn, President, National Safety Council.

- Thomas H. MacDonald, Commissioner, Bureau of Public Roads.

- Curtis W. McGraw, Chairman of the Board, The McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

- Dr. Robert Sproul, President, University of California

- Bertram D. Tallamy, Superintendent, New York State Department of Public Works and President of AASHO.

Entries had to be postmarked by midnight, March 1, 1953, and received by March 14, 1953. The judges, who would review numbered, unsigned submissions, would evaluate the essays on originality, sincerity, and practical adaptability.

GM President Charles E. Wilson announced that the contest was designed to energize "a great national education program." To generate interest, GM's advertising budget for the contest far exceeded the amount of prize money. The announcement of the campaign included a technicolor film, dinners in key cities, and advertisements in hundreds of newspapers and magazines. As Road Builders' News, the magazine of the American Road Builders Association, put it, "This announcement made on November 12 caused hundreds of thousands of Americans to grab their lead pencils and start studying up on roads and streets."165

The Winning Essay

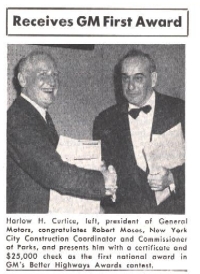

Approximately 44,000 entries were submitted. The winners were announced by GM's new President, Harlow H. Curtice, at a dinner in Detroit's Statler Hotel on June 18. The $25,000 top prize went to Robert Moses, the 64-year old New York "power broker" who was then at the height of his power. His titles included Construction Coordinator for New York City, Commissioner of Parks for the city, and Chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. Biographer Robert A. Caro said of Moses:

Robert Moses possessed at the time . . . an imagination that leaped unhesitatingly at problems insoluble to other men . . . and that, seemingly in the very moment of the leap, conceived of solutions. He possessed an iron will that put behind his solutions and dreams a determination to let nothing stand in their way.219

His legacy can be seen throughout New York City as well as New York State-great bridges such as the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, expressways and parkways, tunnels, apartment houses, public beaches, hydroelectric power dams, and landmarks such as Lincoln Center, Shea Stadium, and the United Nations headquarters. He affected the shape of national parkways and expressways, and played a role in development of the Interstate System.

But Moses was controversial, and had a way of brushing critics aside as if they were mere irritants. And today, the legacy of Robert Moses is as often cursed as praised - perhaps more often cursed and his methods have become a model of how today's public works professionals should not act. Caro observed that Moses was "America's greatest builder," but to earn that title, Caro added that Moses had dispossessed hundreds of thousands of people, destroyed lively communities, flooded the city with cars while starving the subways and suburban commuter railroads, and ensured the sprawling, low density suburban development pattern relying on roads that "would continue for generations if not centuries."220 Caro's ambivalence about the subject of his biography is illustrated by the index entry on Moses, which includes such subjects as "brilliance," "charm," "idealism," and "imagination" as well as "bullying," "deviousness," "divorced from reality," "end justifying means," "imperial style," and "self-glorification."

As for Moses, he warned those considering a career in public works:

The prudent, conservative, pedestrian soul who wants every course neatly plotted out and tested, every accident and emergency guarded against, every contingency covered, should keep religiously away from the permanent, unprotected public service, because it is fraught with danger to you and yours, full of the unpredictable and unpremeditated, the freakish, illogical, bone-chilling, narrow shaves, and the dubious favors of Lady Luck.221

The award winning essay was called:

How to Plan and Pay for

The Safe and Adequate Highways We Need

Moses began his award winning essay with the statement that, "The highway dilemma is a major concern of every man, woman and child in the country." The problem could be easily stated: 53 million cars are riding on roads that are "by and large inadequate in mileage, location, width, capacity, and durability." They were, moreover, "unsafe, of inferior, dated design and poorly lighted and policed."

He estimated that an adequate road system "if we could get it in, say, ten years, would cost about fifty billion dollars." He was referring not simply to building the Interstate System, but improving the entire road network. Readers, Moses suggested, might think 10 years "seems unduly long." But considering "practical difficulties," such as defense and housing needs that were pulling resources from road building, 10 years was about right. Even beyond the practical difficulties, time was needed simply to build the projects, especially in urban areas where the need was greatest:

[The] minimum schedule of major highway building in urban areas runs to at least three years for each large project-a year to design and sell the plan to those whose support is needed to lift it from idea to reality, and at least two years to clear and prepare the site, build on it and landscape it.

For Moses, there was no debate about whether the BPR should continue to play a role, contrary to what many Governors and some State highway officials believed. He described what the Nation would be missing if not for the BPR:

. . . we should have no national through routes uniting all sections of the country, few comprehensive long range state programs, no uniformity of design, no progress in the less populous and prosperous states and municipalities, no official leadership, no continuing Congressional support and no formula for federal aid.

What was needed was a coordinated effort by the BPR, the State highway agencies, the toll authorities, municipal governments, and regional bi-State bodies. Amidst "a complex administration of highways," as at present, he believes that the "federal government must set the pace, that it must contribute a proportionately larger percentage of aid to routes of more than local significance and that it must continue to raise and enforce standards."

Raising money for a $50 billion, 10-year program would require "more federal aid for main and subsidiary routes, more state and local bond issues involving the general credit, and more special bond issues supported by capitalized auto revenues." In addition, bonds would have to be floated by regulated public, regional, bi-State, State, and municipal authorities.

For the Interstate System, Moses had specific advice on financing. He explained that it would cost at least $11 billion, but included highways that were "potentially wholly or partially self-liquidating" (that is, they could be built as turnpikes):

The present policy of the Congress and the Bureau of Public Roads, which bars the expenditure of federal highway funds on toll highways, should be reexamined.

Through a change in policy, Moses thought that a combination of Federal-aid and toll financing could fund construction of many Interstate routes.

He dismissed the idea of excess condemnation, which had been favored by President Franklin D. Roosevelt; a wide right-of-way would be acquired so unneeded portions could be sold or rented as a way of subsidizing construction of the highway.222 Aside from the fact that many State constitutions forbid the practice, the amount of money to be raised in this way "has in most instances been greatly exaggerated." Further, speculation in land, even by the most reliable public officials, would "lead to widespread suspicion and, human nature being what it is, to irregularities."

Moses included a table that summarized his financing program by showing the changes that would add up to a $50 billion program:

Double the present federal aid allotment to the states, the income to be derived from segregation of a 3-cent federal gas tax plus the present 6 cents per gallon tax on oil ($12.5 billion over 10 years).

Raise average gas tax in 48 states ½ cents and increase truck tax. State highway user revenue will then total $3,450 Millions annually.

Deduct from this amount $1,400 Millions annually, representing average of 2 cents of gas tax and half of registration fees, capitalize this revenue and issue bonds backed by it ($23.3 billion).

Remainder of State Highway User Revenue ($20.5 billion).

Construct $4,000 miles @ $1.2 Millions per mile with proceeds of revenue bonds of public authorities and similar agencies ($4.8 billion).

Municipal government expenditures including moderate increase ($12 billion).

His plan added up to $73.1 billion, but was reduced to $50 billion after subtracting the cost of maintenance and administration ($23.1 billion).

The key to success was a strong Federal role:

There would be a great incentive to states and municipalities to do their share if the President were to recommend and Congress were to pass legislation offering such additional aid on the basis of this new formula.

The remainder of the essay stressed the importance of eliminating railroad-highway grade crossings, controlling parking in urban areas, developing uniform safety measures, and controlling of billboards.

To generate support for the 10-year program, Moses recommended that every legitimate influence, effort, and means be used. Imaginative exhibits, similar to GM's Futurama, should be shown around the country to acquaint the layman "with the stirring drama of the ten year program." Gasoline, oil, tire, and other related businesses should "put their shoulders to the wheel," along with safety organizations, the press, and elementary schools, high schools, colleges, universities and other similar forums. The Council of State Governments, American Association of State Highway Officials, the BPR, the Governors, the Highway Committees of Congress, the Conference of Mayors, and others should work together on the program. The slogan for the campaign would be:

Good roads for good cars

Support the Ten Year National Highway Program

In conclusion, Moses stated:

By such means we can have, before 1953 is over, general agreement on an adequate program and schedule with enough flexibility to insure the cooperation of the national, sectional and diverse other interests which control our motorized civilization.223

When Moses included excerpts of the award-winning essay in his 1970 book, Public Works: A Dangerous Trade, he reminded his readers that the essay appeared in 1953, "when the recommendations since adopted were novel, disturbing, and controversial."224

At the Detroit dinner announcing the winners on June 18, 1953, Moses gave a brief address, praising the contest because it had "stirred up the public, and countless daily irritations will keep them agitated." He added, "It is good American doctrine to get ideas first, instead of having a plan imposed by fiat."

The Second National Award, worth $10,000, was presented to Brigadier General Lacey V. Morrow, Director of Competitive Transportation for the Association of American Railroads. Third prize ($5,000) went to Claude A. Rothrock, Chief of the Planning Division, West Virginia Road Commission.

President Curtice stressed that stirring up the public was the point:

But the real success of the contest is not something that can be measured only by the ideas or suggestions that were offered. The important thing is that the contest has stimulated many people all over the country to concern themselves more seriously with the fact that our national highway transportation system is becoming increasingly inadequate to meet the ever increasing demands upon it.

165 Editorial, "GM's Highway Awards," Road Builders' News, November-December 1952, p. 2. Eisenhower chose Wilson, the highest paid executive in the world, for the $22,500-a-year post of Secretary of Defense. To gain Senate confirmation, Wilson had to sell $2.5 million in GM stock (GM was the Nation's largest defense contractor). Before long, according to Brendon, Wilson "was reducing Ike to paroxysms of rage by his rambling discourses in the White House and his appalling gaffes outside it." (p. 231)

219 Caro, Robert A., The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1974, p. 3-4.

220 Ibid., p. 18-19.

221 Moses, Robert, Public Works: A Dangerous Trade, McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1970, p. xxii.

222 Moses had served under Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York. As depicted by Caro, they had a complicated relationship, with the Governor disliking Moses the man but appreciating Moses the master builder.

223 Excerpts from "How to Plan and Pay for the Safe and Adequate Highways We Need," by Robert Moses, from the Announcement of Winners, General Motors Better Highways Awards Contest, June 18, 1953.

224 Moses, p. 280.