President Truman and the Action Program

President Harry S. Truman, who had been a road builder as a young man and an avid motorist his whole life, had also been concerned about the growing traffic safety problem-and with good reason.

Fatalities had reached 39,969 in 1941 before restrictions on driving during World War II (such as rationing of gasoline and tires and reduced speed limits) and the departure of many motorists for military service resulted in reduced highway deaths of 23,823 in 1943 and 24,300 in 1944. After the restrictions were lifted after the war ended in mid-1945, highway deaths increased to 33,500 in 1946.

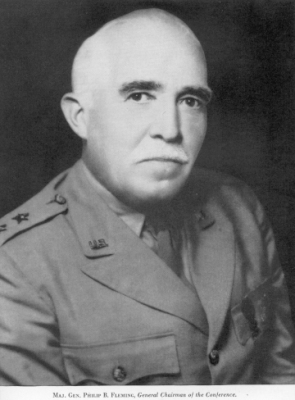

On December 18, 1945, President Truman wrote to Major General Philip B. Fleming, Administrator of the Federal Works Agency (which included the Public Roads Administration (PRA)), to express concern about "the extent of traffic accidents on the Nation's streets and highways which have increased alarmingly since the end of gasoline rationing." The loss of lives, bodily injuries, and property destruction were "a drain upon the nation's resources which we cannot possibly allow to continue." The President said:

It is my intention to call into conference at the White House next spring representatives of the States and municipalities who have legal responsibility in matters of highway traffic, together with representatives of the several national organizations which have a primary interest in traffic safety. I hope that additional means may be devised by such a conference to make our streets and highways safer for motorists and for the public before the beginning of the automobile touring season of 1946.

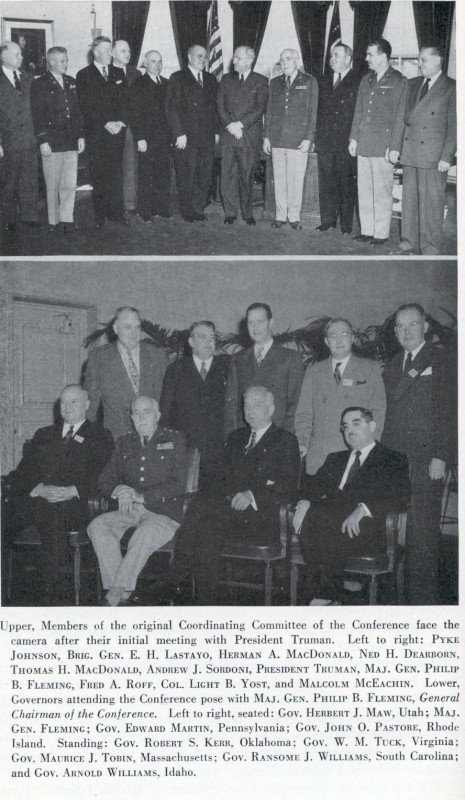

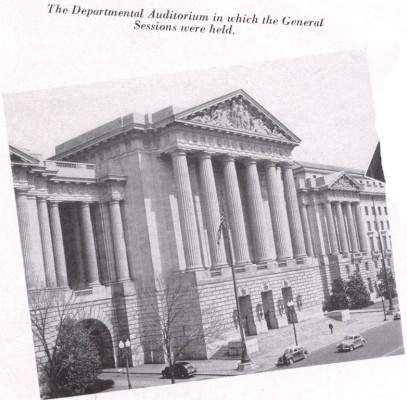

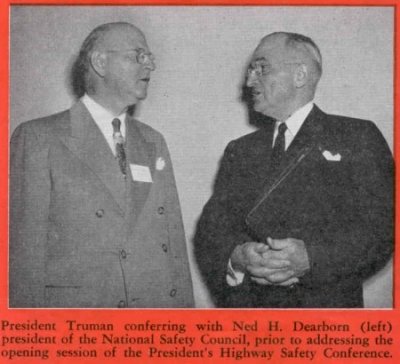

He asked General Fleming to serve as general chairman of the President's Highway Safety Conference, which would be held on May 8 to 10, 1946, in the Departmental Auditorium on Constitution Avenue in Washington. The PRA provided most of the conference staff and aided in preparing and assembling reports to the conference.

The 2,000 participants included Federal, State, and local officials, civic leaders, highway transportation and traffic technicians, and leaders of national organizations. Public Safety magazine, published by the National Safety Council, described the opening:

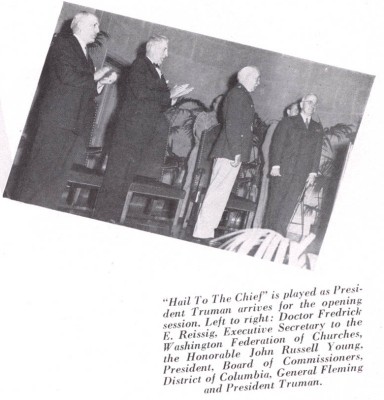

From the very start the conference was impressive. The invocation at the opening session marked a note of solemnity. Then came the dramatic highlight of the day, when the scarlet-jacketed Marine Band struck up the traditional greeting to the Chief Executive of the United States of America-"Hail to the Chief"-and General Chairman Maj. Gen. Philip B. Fleming introduced the speaker with the words, "Ladies and gentleman-the President of the United States."

As the President stood at the speaker's platform and the audience rose to honor him, it marked the first time in the history of the United States that a President had addressed such a gathering.

The President told the participants, "The problem before you is urgent." He referred to the increased number of fatalities since travel restrictions had been lifted after World War II. "During the three days of the Conference, more than one hundred will be killed, and thousands injured," he said.

He told the participants that he had studied the problem when he was in the Senate. "I found at that time that more people had been killed in automobile accidents than had been killed in all the wars we had ever fought, beginning with the French and Indian wars." This was a "startling statement," but he added that, "More people have been injured, permanently, than were injured in both the World Wars-from the United States."

Public Safety's account of the conference referred to the "hush of expectancy" as the President had begun to speak:

Delegates were stirred by the intense and personal interest Mr. Truman injected into his remarks. And, when the vigor of his interest forced him to lay aside his carefully prepared address and launch into one of the most vehement and vitriolic attacks on reckless driving ever delivered by a high government official, even the trim MP's stationed at each side of the speaker's platform were startled out of their impassive rigidity.

Speech put aside, Truman criticized State driver licensing requirements, including those in his home State of Missouri:

You know, in some States-my own in particular-you can buy a license to drive a car for twenty-five cents at the corner drug store. It's a revenue-raising measure. It isn't used for safety at all.

He added:

It is perfectly absurd that a man or a woman or a child, can go to a place and buy an automobile and get behind the wheel-whether he has ever been there before makes no difference, or if he is insane, or he is a "nut," or a moron doesn't make a particle of difference-all he has to do is just pay the price and get behind the wheel and go out on the street and kill somebody.

And that is actually what happens.

As a United States Senator, he had studied the problem of driver licensing:

Some States, at the time I made this investigation-I think there were seven or eight, including the District of Columbia-had license requirements which required drivers to know something about running a car-certain safety signals, to know a green light from a red one, to know which hand to put out when he was going to turn right or left.

He had tried to pass legislation to impose certain requirements on drivers, but the bill had failed in the House of Representatives because of a concern about the States' right to control operation of their highways. He agreed that the State and local governments were responsible for highway construction, licensing of drivers and vehicles, regulating traffic flow, and deciding on driver instruction in the schools:

Now that is the responsibility of State Governments . . . . It is not intended that the Federal Government shall encroach upon the rights and responsibilities of the States. At the same time, we cannot expect the Congress and the Federal Government to stand idly by if the toll of disaster continues to go unchecked.

Given the difficulty of securing Federal action, the President challenged the participants:

But they have been standing idly by for the last 25 years, and I think they will continue to stand idly by, unless you do something to force the control of this terrible weapon which goes up and down our roads and streets all this time. The challenge must and will be met. I firmly hope and believe that every agency of government, backed by the aroused support of its citizens, will meet its responsibilities fully in this field.

The President was certain the public would respond wholeheartedly to appeals for safe and sensible conduct. Beyond that, "modern techniques of enforcement, engineering, and education" could help make communities safe. The techniques, he said, would be discussed during the conference. He concluded:

Out of their studies and reports, you can formulate a uniform and balanced highway safety program. I urge you to take this program back home with you, and to take whatever steps are needed to see that it is adopted.

I also appeal to every driver and pedestrian for cooperation in making our streets and highways safer. Give this program your earnest and continuous support, individually and through organized effort. In that direction lies the promise of a safer and a happier United States of America.

According to Public Safety's account, "The thunderous roar of applause that greeted his remarks left no doubt that the gathering would produce a program to fulfill his hopes and expectations."

One result of the conference was an Action Program to combat highway deaths and injuries. It addressed collection and analysis of accident records, adoption of a Uniform Vehicle Code and Model Traffic Ordinances to cut confusion over road rules, education in the schools, increased enforcement of traffic laws, improved highway design to eliminate hazards, adoption of sound driver and motor vehicle licensing requirements, and an aggressive public information campaign.

Another result was Executive Order 9775, which President Truman signed on September 3, 1946. The Executive Order established the Federal Committee on Highway Safety, as recommended by the President's Safety Conference. The Federal Committee included representatives of 13 Federal Agencies:

- Public Roads Administration

- National Bureau of Standards

- Bureau of the Census

- Federal Works Agency

- Office of Education

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of the Interior

- Department of War

- Department of the Navy

- Post Office Department

- Interstate Commerce Commission

- Federal Interdepartmental Safety Council

General Fleming was chairman, while Commissioner of Public Roads Thomas H. MacDonald served as chairman of the Executive Committee of the Federal Committee.

The purpose of the Federal Committee was:

The Committee shall promote highway safety and the reduction of highway traffic accidents and, to this end, shall encourage Federal agencies concerned with highway safety activities to cooperate with agencies of State and local governments similarly concerned, with nationwide highway safety organizations of State and local officials, and with national non-official highway safety organizations, as the Committee may determine. The Committee shall also, to the extent permitted by law, coordinate the highway safety activities of Federal agencies.

The Executive Order also asked the head of each of the Federal Agencies to take "such measures within his sphere of responsibility as will result in improved highway safety conditions; to cooperate with the Committee with a view toward attainment of improved highway safety conditions; and, consonant with law, to provide the Committee with necessary staff assistance."

The President's Second Highway Safety Conference

The President sponsored a second Highway Safety Conference in Washington on June 18-20, 1947, to review progress in highway safety and develop additional ways of implementing the Action Program. The conference, again under the general chairmanship of General Fleming, had been requested by three national committees created after the original session:

- State and Local Officials' National Highway Safety Committee,

- National Committee for Traffic Safety, and

- Federal Committee on Highway Safety.

(The National Committee on Uniform Traffic Laws and Ordinances, which had been in operation for many years, joined the President's Highway Safety Conference as its fourth committee in Fiscal Year 1950.)

Once again, President Truman was the special guest on the first day of the event. Public Safety set the stage for his speech:

The words of the opening sessions threaded the serious import of the Conference with a note of marked solemnity. The dress uniforms of the Marine band formed a spot of color in the highlight of the meeting, when the strains of the nation's traditional greeting to the Chief Executive brought the audience to its feet to honor him, as Maj.-Gen. Philip B. Fleming, the general chairman, ushered him to the speaker's platform with the words of introduction: "Ladies and Gentlemen, the President of the United States."

Flanking the President on both sides and across the back of the stage, a guard of honor stood rigidly at attention. Comprising picked officers from state and city law enforcement agencies, and commanded by Col. C. W. Woodson, of the Virginia State police, they represented the enforcement effort of the whole nation. Their presence on the platform witnessed the President's high regard for the agencies they represented.

After greeting the delegates, the President summarized the "problem of prime importance to every resident of our Nation." He began by citing the Nation's increased traffic-nearly 350 billion vehicle miles in 1946, a 4-percent increase over volumes in 1941:

In a very real sense, the increase in post-war highway travel is a measure of our return to the happier peacetime pattern of life in America. There is one tragic aspect of that pattern, however, that no one wishes to see restored. I refer to the appalling destruction of life and property through highway accidents.

After noting that 40,000 lives were lost on the Nation's highways in 1940, he said that in 1946, "with travel 4 percent higher, an even greater loss would have been sustained if the prewar death rate had continued." He was referring to a comparison of the fatality rate (deaths per 100 million vehicle miles, a way of comparing fatalities over time as traffic volumes change):

Fortunately, that did not happen. Beginning in May 1946, the highway fatality rate showed a sharp and gratifying decline. Last year, the rate was 9.8 deaths per 100 million vehicle-miles, compared with 12 in 1941.

The result was that at least 6,500 lives had been saved, "a major victory in the campaign against carelessness." The major share of credit "must go to the efficient and devoted efforts which were set in motion at the first Highway Safety Conference here in Washington in May 1946." The results demonstrated what could be achieved "through the concerted effort of motorists and pedestrians, under the leadership of governmental agencies and with the support of organized groups of public-spirited citizens."

In 1946, 33,500 men, women, and children had been killed in highway accidents:

If those deaths had occurred at the same time in a single community, the whole world would have been profoundly shocked. Every resource of the United States would have been mobilized immediately to prevent the recurrence of such an awful tragedy.

The challenge is no less urgent because it is less spectacular.

Given the initial success, the next goal must be to increase compliance with the Action Program throughout the country. Encouraging progress had been made in safety education, especially driver education in high schools. He was discouraged by the limited progress on driver licensing. Two additional States had enacted driver license laws, leaving only one State without such a law:

But uniformity is still lacking among the States. And in too many jurisdictions, as I have pointed out before, the licensing laws are nothing more than revenues measures and their administration a travesty on public safety.

He added that the States had made little progress in raising the standards of motor vehicle administration.

Considering that licensing and standards were basic weapons in "the war on accidents," the present situation "cannot be permitted to continue indefinitely." As he had said in 1946, he did not want the Federal Government to encroach on State jurisdiction, but he did not believe the Congress would "stand idly by in the face of a grievous national accident toll." Highway safety was a "direct concern" of the Federal Government, which could do much, short of encroaching on State jurisdiction, to reduce the tragic toll:

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944, for example, provides for the development jointly with the States of modern traffic arteries, both rural and urban, which will incorporate maximum safety into their design and construction. Improvements of this kind in the highway plant will make a permanent and substantial contribution to accident prevention.

He was referring to the provision of the 1944 Act that authorized the Federal Works Agency to designate a 40,000-mile National System of Interstate Highways as the backbone of the Nation's highway network. Because the designation process was not accompanied by special funding or a Federal commitment to build the network, little progress would be made until the mid-1950s.

Although "vigorous progress" had been made under the Action Program, many shortcomings remained:

The purpose of the meeting is to weigh the strength and the weakness of the current program, and to outline further steps which can be taken to speed the adoption of the "Action Program" by all jurisdictions.

Public Safety reported:

The thundering ovation rendered the President at the close of his address left no doubt but that the gathering would find ways and means of strengthening the program by coordinated effort to meet specifications demanded by increased travel and more cars in time to fulfill his hopes and expectations.

An editorial in the weekly newspaper of motor freight carriers, Transport Topics, agreed that progress in the past year had been "gratifying." The reduction in the fatality rate was one-third of the way to the goal of 6 per 100 million vehicle miles by 1949.

In other words, one-third of a three-year job was done in the first year indicating that safety progress was on schedule.

Furthermore, experienced safety men say that the accident reduction progress made in the single year probably was as great as normally would have occurred in four or five years-a tribute to the President for taking a personal hand in the safety movement and to those who have sparked the Conferences.

For all the progress, the editorial acknowledged the remaining challenge:

The one-third cut in the accident rate thus far accomplished is the "easy" third. Now that the cream has been skimmed from the accident-reduction bottle, concrete plans must be put into effect to produce the other two-thirds in the way of accomplishments.

Although President Truman did not convene a national conference in 1948, the Committee on Conference Reports met in the summer to study reports submitted by eight technical committees. The Governors of 44 States assigned official delegates. One of the major results of the meeting was an inventory of traffic safety activities to serve as an annual score card the States and cities could use to measure the effectiveness of their safety programs.

The PRA's annual report for 1948 summarized the progress since the first conference:

This annual inventory of the advances in highway safety under the action program of the President's Conference revealed that the fatality rate declined from an average of 12 deaths per hundred-million vehicle-miles of travel in the decade 1936-45, to 9.9 in 1946, 8.6 in 1947, and 7.5 during the first four months of 1948.

The committee voted to hold a third nationwide meeting in Washington. President Truman agreed to do so, noting that progress since 1946 had been "steady and gratifying."

The President's 1949 Highway Safety Conference

With General Fleming as General Chairman, the President's Highway Safety Conference took place on June 1 to 3, 1949, in Washington. About 2,500 delegates representing the 48 States, cities, counties and organizations concerned with highway safety attended the conference, along with more than 100 representatives of 32 foreign countries.

The general sessions on June 1 and 3 were held in the Departmental Auditorium on Constitution Avenue. On June 2, the delegates gathered in Constitution Hall. Once again, the Marine Band struck up "Hail to the Chief" and General Fleming introduced the President. Public Safety set the stage:

As the President stood at the speaker's platform and the audience rose to honor him, it marked the third time in the history of the United States that a President had addressed such a gathering. Significantly enough, it was President Truman who established each such high water mark in the history of traffic safety.

The President told them that results since the 1946 conference were encouraging, as "a substantial number of States and communities" had adopted the safety program. He estimated that as a result, 11,000 lives had been saved, and injuries to 400,000 people had been prevented. "Nevertheless," he said, "the frightful slaughter on our streets and highways continues." In 1948, the total of 32,000 people killed in highway accidents was more than twice as many as were killed "in all the American Forces during 6 weeks of the Normandy campaign in 1944," referring to the D-Day invasion of France on June 6, 1944, that marked the Allied initiative to end World War II.

He pointed out that 429 people lost their lives during the Decoration Day weekend (the original name, dating to 1868, of Memorial Day), half of them in traffic accidents:

Now, if a town had been wiped out by a tornado or a flood or a fire and killed 429 people, there would be a great hullabaloo about it. We would turn out the Red Cross, and we would have the General declare an emergency, and I don't know what-all. Yet, when we kill them on the road, or unnecessarily drown them in accidents that shouldn't happen, we just take it for granted. We mustn't do that.

He was disappointed that some States had failed to establish driver licensing systems "worthy of the name." He said:

I am sorry to relate that my great State of Missouri is still in that column. Terrible! Why, a man can go down to a drugstore from an insane asylum and spend a quarter and get a license to drive on any road in that State, if he wants to.

Even States and cities with strict rules suffered from the lax controls in other States:

Here in the District, not long ago, whose driving laws are very strict, they found four men who couldn't see an inch in front of their noses, with driving licenses issued by one of these 25 States that don't take care of their populations.

He stressed the importance of driver education:

It takes years and years, you know, for a man to drive a steam engine down the tracks which it can't get off, yet we let anybody get a driving license for an automobile whether he knows front from back or right from left.

He told delegates, "State and local governments have a duty to deny the privilege of using public highways to the irresponsible, the unfit, and the chronic law violators." He did not repeat his threat of Federal intervention, but said the American people would support "sensible regulations, capably administered" to protect life and property.

He endorsed the annual inventory of traffic safety activities, developed in 1948, as "a useful yardstick and factual guide" that communities can use to measure their progress. He also was encouraged by increasing highway construction, which had gained momentum the last 18 months "after considerable delay due to shortages of materials and other factors":

The modern features which are being incorporated into new and reconstructed arteries of travel will go far toward eliminating head-on collisions and some of the other more severe types of accidents.

Progress was also being made in other areas, including improvement in the administration of traffic courts and enactment of uniform motor vehicle laws and ordinances. He summed up:

All in all, this conference can review a record of solid accomplishment. At the same time, you face clearly defined needs for more intensive work.

Given the progress to date in implementing the Action Program, the President was "confident that you will succeed" through teamwork:

This entire program has been developed and set in motion by voluntary teamwork. And the spirit which makes it possible is the spirit of a free people and the guarantee of our system of democracy.

According to Public Safety, "Delegates were obviously stirred by the vigor and the intense personal interest of the President's remarks."

An engineering progress report was released during the conference in support of the President's comments about the safety benefits of increased highway construction. According to the report, most construction involved two-lane designs (94 percent of 18,195 miles), but the ratio of divided highways and undivided highways built was in excess of 5 to 1. Accident prone three-lane roads (a highly dangerous design that had once been popular because the center lane allowed for passing) were declining. The number of grade separations for highway intersections (119 locations) and rail-highway crossings (114) had increased in 1948 over the previous year. Also up were channelized intersections, lighting, sidewalks, marked crosswalks, centerline markings, no-passing zones, and highway signs and signals.

During the conference, participants agreed on a nationwide campaign to reduce the highway traffic death rate by 40 percent in the next 3 years. State, municipal, and safety organizations were urged to work toward a goal of reducing the national highway death rate to 5 persons per 100 million vehicle-miles traveled.

General Fleming told participants that he did not consider the goals "at all visionary." The goals could be reached, he said, if all interests carried out a dynamic highway safety program. However, he summarized the frustrating reality of the highway safety situation:

Three years of activity since the initial President's Highway Safety Conference has taught us several important lessons. We have found that the action program is sound, practicable, and comprehensive. Yet, the highway death toll continues to be a national disgrace. The fault lies, not in the action program itself, but in its uneven application.

Based on the technical committee reports during the conference, participants updated the Action Program. The revitalized Action Program involved seven main points, as summarized in a Department of Commerce press release dated May 12, 1952:

- Adoption of the Uniform Vehicle Code and the Model Traffic Ordinance in the interest of uniformity in traffic laws and regulations.

- More effective collection and analysis of traffic-accident reports and use of these reports in guiding highway-safety activities.

- The continuance in all American schools of traffic-safety programs to give guidance in accident prevention.

- The operation of continuing traffic-law-enforcement programs in cities and states that will stimulate maximum voluntary observance of regulations by creating adequate deterrence to violators.

- Use of engineering principles and techniques to eliminate or reduce physical hazards and to promote the safe control of traffic movements.

- Adoption by the States of sound policies and procedures in the field of motor-vehicle administration, with special attention to driver licensing and vehicle inspection.

- Continuance by all public information media to spread the word about highway safety-and the lack of it-to the public.

Highway Safety for National Defense

The Federal Works Agency was eliminated in a government reorganization in 1949, resulting in a shift of the PRA to the Department of Commerce and a change in the name of the PRA to its earlier name, the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR). President Truman appointed General Fleming to be Chairman of the Maritime Commission, but retained him as General Chairman of the President's Highway Safety Conference.

The Committee on Conference Reports met again in 1950, with special emphasis on rural roads. The BPR's 1950 annual report explained the reason:

Due to the tremendous increase in highway traffic, from less than 250 billion vehicles-miles in 1945 to more than 424 billion in 1949, the highway accident problem remained critical. The conference gave special consideration to the threat that for the first time in the 4-year history of the action program for traffic safety, the annual increase in traffic deaths outside of cities may more than offset the annual decline in urban centers.

The decline in the fatality rate encouraged backers of the Action Program, but the Committee on Conference Reports placed renewed emphasis on controlling traffic on rural roads.

President Truman wrote to General Fleming on August 30, 1950, to outline steps to be taken to increase highway safety. In the previous 2 months, North Korea had invaded South Korea, prompting the President to join with the United Nations Security Council in a war to repel the invasion. The President, therefore, began his letter to General Fleming by noting that, "Highway transportation is of the utmost importance to the national defense." It must be maintained "at the highest point of safety and efficiency." Immediate steps must be taken, he told General Fleming, to increase efficiency in the use of highway transportation facilities and coordinate action to ensure movement of defense commodities and military traffic.

Citing the declining fatality rate on the Nation's highways ("less than 7 during the first 6 months of 1950"), he wanted to build on the existing cooperation with State and local officials "to assist in the safe and efficient movement of increasing amounts of defense materiel and military traffic." He asked the General to evaluate how each State was applying the Action Program and determine how deficiencies could be reduced; use this analysis to ask States, communities, and private groups to increase their emphasis on highway safety "in the interest of conserving manpower, equipment, materials and highway facilities in the light of their increasingly critical importance"; cooperate with the Governors' Conference to enhance highway transportation; and work with the Department of Defense "to expedite highway movements in the safest and most efficient manner in the event of an emergency."

On February 22, 1951, President Truman announced he would convene the President's Highway Safety Conference in Washington in June:

Preliminary figures for 1950 indicate that the number of deaths approached 35,000, personal injuries were suffered by 1,200,000 and the economic losses are estimated at $2 ¼ billion. The figures for last year are the highest since 1941 - the all-time high year. This is the price the American public has paid for carelessness, ignorance, disregard of the law and inefficient driving.

The toll can be reduced. A practical program of action was developed at the first national conference, which I called in 1946, and it has demonstrated encouraging results. For the nation as a whole, the number of traffic deaths has been cut from 11.3 per 100 million vehicle miles of travel in 1945 to less than 7 in 1950. The program has reduced accidents wherever it has been applied.

However, it has not offset the huge increase in motor vehicle usage. Today 48 million automobiles, trucks and buses operate over our street and highway network, compared with a 1941 pre-war peak of 34.5 million. Safety activities must be enlarged and intensified to match this greatly increased exposure to accident.

In the months since the United States entered the Korean War in July 1950, the President had come to see the highway safety crusade as part of the defense effort. The need for a strong America, he said, made traffic safety "doubly urgent . . . . The defense effort depends upon the efficient movement of goods and people over public highways and roadways."

General Fleming was to serve as general chairman of the 1951 conference, but he was confined by illness to Walter Reed Army Hospital. Secretary of Commerce Charles Sawyer, presiding over the conference in the General's absence, introduced President Truman as the keynote speaker at the opening session on June 13 in Constitution Hall. The President told the delegates that in this time of war, the highway safety campaign was more important than ever:

This need for a strong America makes your work doubly urgent. Highway accidents strike directly at our national strength. A highway accident does just as much damage to the defense effort, as a deliberate act of sabotage by a hostile agent.

The defense effort depended as much on efficient highway transportation as railway transportation. Traffic accidents "slow down production and weaken our whole economy" because of "carelessness and inefficiency."

He reported on the progress under the Action Program since he had convened the first highway conference 5 years earlier. With the fatality rate declining, he said, "What we need to do now is to find a way to bring the accident rate in every State and city down to the level of the best record-and even lower."

Lowering the fatality rate was a sign of progress, but "the sad fact is that, in spite of the progress we have made . . . the total number of accidents is going up." He explained that as travel mileage "skyrocketed," 35,000 people were killed and more than a million injured in traffic accidents. He said that in the last year, total casualties (killed, injured, captured) in Korea totaled less than 80,000, and that figure "is on the mind and tongue of every citizen." He took the opportunity to take a poke at his critics:

But right here at home we kill and permanently injure a million and [kill] 35,000 people, and there is no outcry by the sabotage press, no misstatement by the columnists or the congressional demagogues.

If, he thought, "those fellows" wanted to pick on his Administration as it helped fight a war, here was an opportunity "and they ought to make use of it," but they did not do so.

To avoid setting a record in the number of traffic deaths, the first step was to improve highways. Because of the Depression in the 1930's and the disruption of World War II, highway progress had lagged for 20 years even as the number of vehicles had increased. "Much of our main road mileage is worn out and obsolete, and the replacement program has not kept pace with the increased use." The highway program had expanded since the end of the war in 1945, but difficulties were again arising in diversion of construction materials for the war effort in Korea:

Some highway projects may have to be deferred. But good roads are essential, and we must not make the mistake of thinking that highways are expendable in an emergency period.

Safe roads were not enough, of course; "we must have safe drivers." Driver education, particularly in high school, had been increasing, a fact that promises "a great deal for the future."

The key to continuing progress, he felt, was "the continuous and intelligent support of the American people." Each citizen had a personal responsibility to support highway safety:

This will take self-discipline, but it can be done. It's a simple matter of good citizenship.

He then dramatized the issue by pointing out that at some point in 1951, "the number of traffic deaths since 1900 will pass the million mark":

Nearly as many Americans have been killed in automobile accidents as have been killed in all the wars of our history, beginning 175 years ago with the War for Independence.

He pointed out that monuments had been erected to the men and women who gave their lives "for the purposes to which this Nation is dedicated." They died in a noble cause, "But there is no noble purpose in death by traffic accidents." He called on the delegates to "go home and get others to join you in vigorous support of the highway safety program."

Having concluded the safety portion of his address, President Truman took a moment to address General Fleming's wife, who was in attendance. The President explained that on May 7, 1946, he had given the Army Distinguished Service Medal to General Fleming for his direction of a construction program of Army and Navy buildings in the United States, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Central America during the war. Since then, General Fleming "has rendered equally distinguished service in several posts, including his work as permanent general chairman of the President's Highway Safety Conference." Therefore, the President asked Mrs. Fleming to accept a gift from the Highway Safety Conference:

Let me read the inscription: "Philip Bracken Fleming. In appreciation of his immeasurable service, and unfailing guidance in the cause of highway safety"-the President's Highway Safety Conference presents this. And I present it for the conference in the name of the President of the United States.

The BPR's annual report for 1951 summarized the results of the conference:

The 1951 session emphasized the how of applying the action program for traffic safety, which was originally developed in 1946 and revised in 1949, and reviewed the annual conference inventory of advances and weaknesses in highway safety. The inventory indicated that the seriousness of the traffic safety problem has been increasing as unprecedented numbers of vehicles have been registered for use on the highways and as the volume of traffic has mounted since the close of World War II. The total of 35,000 people killed in traffic in 1950 has not been equaled since 1941. Yet, with preventive activity under the action program of the conference, the rate of fatalities has declined from an average of 12 deaths per 100 million vehicle-miles of travel in the decade 1936-45 to 7.5 in 1950.

The 1952 Highway Safety Conference

President Truman decided not to run for reelection in 1952. During his last full year as President, he had many issues on his agenda, including the Korean War. But on April 11, he wrote to ask Secretary of Commerce Sawyer to spearhead a renewed highway safety program and serve as General Chairman of the President's Highway Safety Conference. General Fleming had served briefly as Undersecretary of Commerce for Transportation before President Truman appointed him Ambassador to Costa Rica in 1951, thus ending his service as General Chairman.

President Truman explained the frustrating reality:

In 1950 traffic fatalities reached 35,000. In 1951 this total increased to 37,500 and the National Safety Council estimates that a further increase to the alarming total of 40,000 will result from highway accidents during 1952. Coupled with the bodily injury to more than 1,000,000 persons and monetary losses approaching $3,000,000,000, these staggering totals indicate the need for renewed and increased efforts.

After summarizing the history of conferences under his Administration, President Truman asked Secretary Sawyer to "enlist the active support of business and other civic groups as well as public officials."

On May 12, Secretary Sawyer announced he would establish an advisory committee of outstanding business and industrial executives to examine the highway safety problem. He invited them to the President's Highway Safety Conference on October 17-18 in Chicago's Hotel LaSalle. The goal of the conference was to review progress under the Action Program and devise means of gaining wider acceptance of its agenda.

The President did not participate in the Chicago conference. He was in New England on October 17 campaigning for the Democratic Party's nominee for President, Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, and in New York City for the same reason on October 18.

The meeting of the President's Highway Safety Conference was a prelude to the annual meeting of the National Safety Congress in Chicago (October 20-24). According to Public Safety more than 12,000 delegates were in Chicago for the annual meeting, which was spread among five hotels (the Conrad Hilton, Congress, LaSalle, Morrison, and Sheraton).

Bertram D. Tallamy, New York's Superintendent of Public Works, addressed the President's Highway Safety Conference as Chairman, State and Local Officials, National Highway Safety Committee. He discussed the importance of highway transportation:

Almost everything that you use in your office or in your home, or the cup of coffee you had for breakfast, or the suit of clothes you are now wearing, was dependent upon modern highway transportation at some time or other during its development and distribution.

The cost of transportation, therefore, was a tax "which affects everybody." Part of that cost, Tallamy said, was the cost of traffic accidents, $3.4 billion. He estimated that in New York, the cost of rebuilding the State's highways over 20 years would be $3.7 billion:

In other words, the traffic accident loss alone, last year, would take care of our 20-year program in New York. If you add this terrific traffic loss to the economic loss resulting from unnecessarily high transportation costs which always prevail when efficient trucks have to operate over inefficient highways, you can readily see we are paying for safe modern highways-yet we do not have them. It is ridiculous, but a fact.

He told the delegates he saw two principle avenues to follow. The first was to "expand reconstruction and to repair our existing highway systems just as rapidly as we possibly can do so." This would "require a large amount of money," as Tallamy knew from his service that year as President of the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO). He described a survey the State highway officials had conducted in 1949 on needs of the Federal-aid highway system:

It indicated that it would require $29 billion to bring that system up to a reasonable degree of capacity and safety . . . . In other words, if one could have bought a magic wand, waved it across the country, and transformed worn-out roads to a modern highway system, the wand would have cost $29 billion.

He added a frustrating note about the estimate:

Two years later we made another survey to see how we were getting along, because we had to spend over $3 billion in that period. The results of the latest survey indicate that our deficit is now $32 billion. In other words, even though we spent $3 billion, we are $3 billion worse off in a two-year period because of obsolescence and depreciation.

Considering that the estimate did not include State and local roads off the Federal-aid system, delegates could see, he said, "the problem ahead of us on that one main approach which must be followed if we are ever to get out of this highway dilemma."

The second avenue was to use the existing highway network, during this period of reconstruction, "in the safest and most reasonable manner." The Conference can be particularly effective in advancing this second avenue. The Conference "can, and must, in my opinion use its knowledge and appreciation of the overall highway problem to help make available the necessary funds to expedite reconstruction."

He called for the many State and local agencies involved in highway safety to work together to "create a plan for an immediate attack on the problem of highway safety and the long-range goal of safe and efficient vehicle operation over modern highways." With coordinated official and public support programs, the "inordinate tax which everyone is paying in cash and in sorrow and grief, can be minimized. It is a goal worth fighting for."

Judge Alfred P. Murrah of Oklahoma, Chairman of the National Committee for Traffic Safety, was another featured speaker at the President's Conference. A long-time crusader in the cause of highway safety, Judge Murrah told the delegates that the country was at a crossroads:

We are face to face with the question whether our scientific and technological ingenuity has outrun our moral capacity to assimilate. In short, are we capable of living with ourselves, or shall we commit suicide?

For an answer, he cited one of the 20th century's acknowledged geniuses:

In 1946, Einstein spoke to Americans in a practical sort of way. He said that if mankind was to survive and move to higher levels, a new kind of thinking must pervade our lives; that we must remember that if the animal part of human nature is our foe, the thinking part is our friend; that we can and must use it now, or human society will disappear in a new and terrible dark age of mankind-perhaps forever.

Judge Murrah did not consider it an exaggeration to say that "the future well-being of mankind depends on how we do our job," and particularly how well highway safety crusaders do in enlisting others in the effort. Better highways and streets were being built to accommodate more powerful vehicles, "but we must build more of them." Laws were being enacted to regulate this power and speed, "but we must have more and better laws." Those laws must be enforced in a way that generated respect rather than fear:

Obedience to law must come from the feeling of respect rather than fear of the screaming siren of the "copper."

He said that just the day before, another member of the National Committee for Traffic Safety had asked him, "Now, Judge, when do we get out of the 'resoluting' stage and into the business of saving lives?" Judge Murrah thought this question "pertinent, sincere, and deserves an answer." For the answer, he likened the highway safety crusade to a football game played on home ground: "all over the field of play and in the grandstands is public support." Public support, he said, "is the strategy and the code of the game."

They must find a way to convert the rank and file to the cause. One way sometimes suggested involved the Christian tenet that "I am my brother's keeper." Applying this tenet to highway safety would not be easy:

Someone has said that we never subscribe to the admonition that "I am my brother's keeper" until we need to be kept; that we never appreciate danger until it strikes at our door.

Highway crusaders must, Judge Murrah said, become evangelists for their cause, speaking to civic clubs, cooperating with safety councils, encouraging ministers to speak on the topic from the pulpit. He concluded:

We come to the realization that it is not enough merely to appeal to the mind, we must appeal to the heart and to the soul of man. When we have done that, we will build an organization for safety rooted in the hearts and minds of the individual everywhere-that, my friends, is our goal and there can be no turning back.

Governor Dan Thornton of Colorado also addressed the President's Highway Safety Conference. Without fear of contradiction, he said, reducing the number of traffic accidents was "one of the most positive challenges to public action in the United States." And yet 1952 was headed for a "record of shame" in accident fatalities and injuries.

Since the early days of the Republic, the role of the States had been evolving. From the "early basic functions," such as education and protection of life, the States had adapted to the "rapidly changing and increasingly complex society" of today:

The new age and its millions and millions of motor vehicles has contributed as much toward this change as any one other factor in history. Our adaptation to this development must be positive and constructive; it is a new responsibility of our states.

He warned that the motor age "cannot be dismissed as a temporary frill." It must, he said, "be absorbed as a basic and fundamental function of state government." Further, "we cannot hide our heads like an ostrich and escape a problem which is with us to stay-we are in a motor vehicle age-there is no alternative but to make that age safe for all generations."

The implications of the motor vehicle age, and especially the safety problem, were "staggering." The implications for government were especially important. Government is "a primary device for getting along together," but when citizens ignore the "basic rules of human relationship," government had to step in "to restrict individual freedom and movement in minimizing the continual threat to human life and liberty."

He referred to a statement in the original Action Program: "The primary responsibility for traffic accident prevention lies with government." In other emergencies and catastrophes, such as floods or disease, State government acted decisively. With executive, legislative, and judicial leadership, States enlisted the support of business and industry to help in the crisis. A similar approach "could reduce the unnecessary loss of life due to traffic accidents."

"Now," he asked, "are the states carrying out these responsibilities?" He had to answer that they were not, and there would be two consequences of this failure:

One will be the continued loss of 40,000 lives per year. The other will be in terms of headlines such as these-appearing in our daily papers:

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT TO GIVE DRIVERS EXAM

TRAFFIC VIOLATORS APPEAR IN FEDERAL COURTS

CONGRESS PASSES 50 MPH SPEED LIMIT

NATIONAL ACCIDENT RECORD OFFICES ESTABLISHEDDo these sound drastic? They are.

Are they alarming? They are.

Are they in 1952? They are not, but [they] are headlines of 1962 or 1972 if we do not progress together on a traffic safety program. We have already seen the federal government undertake many functions originally given to the states, because we refused or failed to undertake them and satisfy demands from our citizens. This can and will happen in this field of traffic safety, unless we can prove to our national leaders that we have the will and ability to curb a national disgrace.

These headlines are not of this year; but when they are written, you and I and every state and city official, will say to himself, "It didn't have to happen this way-why didn't we do something way back in 1952 to forestall it?"

After reviewing some of the State failures to address the Action Program, he concluded:

We are faced with the necessity of rededicating ourselves to the original Action Program of the President's Highway Safety Conference . . . . The combination of a balanced official program combined with organized public support of that program will materially contribute to the reduction of the needless slaughter on our streets and highways.

Since President Truman had launched his highway safety initiative in 1946, the fatality rate had declined from 9.7 fatalities per 100 million miles of travel to 7.3 in 1952. However, the number of fatalities was growing. Post-war deaths declined to a low of 31,701 in 1949, before beginning to climb in 1950 (35,000 deaths), 1951 (37,300 deaths), and 1952 (38,000).

In January 1953, President Harry S. Truman returned to private life in Missouri. According to Public Safety, "The traffic death toll for January was 2,840-a 7 per cent increase over the 2,650 deaths in January last year." With a new President coming into office, the BPR's annual report for 1952 stated that the committees of the President's Highway Safety Conference were preparing for "a tremendous step-up in the entire safety program."

Much work remained for the new President.