The Federal System

When President Eisenhower took office on January 20, 1953, he had many issues to confront, particularly the Korean War, which ended in July 1953. But first, the Nation's Governors wanted to raise an issue that they thought the new President would be sympathetic to: the balance between State and Federal authority. This issue had been at the heart of the American political debate since before the drafting of the Constitution, but had taken on new life during the aggressive Presidencies of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945) and Harry S. Truman (1945-1953).

With the first Republican President in office since 1933, the Governors thought they finally had a chance to reverse the Washington power grab.

On January 21, 1953, the day after the President's inauguration, Governor Thornton and Governor Walter Kohler, Jr., of Wisconsin lunched with the President at the White House. In addition to their lunch of fried chicken, the Governors received a White House tour conducted by the President. They also discussed several topics with the President, including the conflicts between Federal and State taxes on the same products, such as gasoline, incomes, and automobiles. Governor Thornton suggested that the Federal Government get out of these fields of taxation, which he said traditionally belonged to the States.

That same day, the Governors' Conference Committee on Intergovernmental Relations and Tax and Fiscal Policy met at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington. In addition to Governors Kohler and Thornton, the committee included its chairman, Governor Alfred E. Driscoll of New Jersey; James F. Byrnes of South Carolina; John D. Lodge of Connecticut; G. Mennen Williams of Michigan; William S. Beardley of Iowa; and J. Bracken Lee of Utah.

The committee had been convened because the Governors' Conference had concluded that, "The tax policies of the federal government have made it virtually impossible for the state and local governments to obtain the revenues which they require." The Governors were particularly concerned about the "levying of taxes upon identical products by both state and federal governments" and wanted the committee to explore the proposition that:

. . . more efficient service to the citizens could be rendered at lower cost if certain of the taxes now levied by the federal government were abandoned to the states in lieu of federal grants-in-aid.

The committee decided that it would first review Federal grants for highways and the 2-cent Federal gas tax that was deposited in the treasury for general government purposes (it had been raised a half-cent to help finance the Korean War). It directed the Council of State Governments to review the issue and provide a report for further consideration.

The Council's report, completed on February 20, 1953, covered the gas tax and Federal-aid highway program:

It is proposed that the Congress reduce federal expenditures by discontinuing the grant-in-aid program for highways, making special provision, however, for those states with large public lands and sparse populations. It is further proposed that at the same time legislation be enacted repealing the federal gasoline tax, thereby permitting the adoption of the two-cent tax in the several States.

Although this change, if enacted, would result in a short-term loss of Federal revenue, the loss would be made up by the efficiency of eliminating "the administrative duplication which now is part of the Federal Highway Act." Also counter-balancing the loss, in philosophy if not dollars, would be the reaffirmation of the States' responsibilities.

Every state now has a highway department with engineering and construction talent of a professional nature . . . . Competent professional people are . . . being attracted and are increasingly being paid salary schedules to insure their retention in the states. With these conditions, many Governors, expert consultants and state legislators are convinced that standards and specifications for road construction and maintenance will be kept at a high level.

That would be "the primary gain to the nation," according to the Council. Further, the Federal and State duplication of effort was "often a waste of engineering personnel." The report amplified this thought:

Countless hours of conference between state personnel and federal officials in approving highway construction and maintenance result in a waste of time on matters which state administrators are capable of deciding for themselves.

The BPR would, of course, be weakened by the proposal, and this was recognized as a potential problem, especially for the Interstate System:

This raises the issue whether the states, acting jointly, cannot themselves supply the necessary coordinating mechanism. Consideration could be given to forming compacts among neighboring states to consult and plan highway programs affecting their regions. A further possibility is the proposal for a compact among all forty-eight states in the highway field.

Another concern was that pressure might be brought on the State legislatures to build local and rural roads, rather than the important, heavily traveled roads:

This, however, is a matter for the individual state legislatures to decide responsibly and responsively. No gains to democratic state government can be achieved by irresponsible appeal to high levels of government in order to avoid making necessary local decisions.

The solution to these problems can be found in the determination by the states, acting singly and in concert, to modernize and maintain a system of highways adequate to support present and emerging highway needs.

The Governor's Conference, as it had in the past, adopted the proposal that the Federal Government relinquish the gas tax in favor of the States.

On February 26, the White House held a conference on Federal-State relations and reducing or eliminating costly programs and duplicate taxation. Congressional leaders and Governor Allan Shivers of Texas, president of the Governors' Conference, and Governors Byrnes, Driscoll and Thornton, joined the meeting, which resulted in an agreement to form a commission to address the issue. The President participated in the conference from its start at 10 a.m., until he departed at 1:45 p.m. for a golfing holiday in Augusta, Georgia.

The President, according to a White House statement after the conference, favored a bipartisan commission that would propose legislation "to eliminate hodge-podge duplication and waste in existing Federal-state relations affecting governmental functions and taxation." The President outlined the purpose of the meeting:

For a long time I have thought that there must be a clarification of the responsibilities of the state and federal governments in many fields of public activity. The federal government has assumed an increasing variety of functions, many of which originated or are duplicated in state government.

Another phase of this problem relates to taxation. The existing systems of taxation, both at the federal and state level, contain many gross inequalities insofar as the tax burden between citizens of different states is concerned. There is often a pyramiding of taxation, state taxes being super-imposed upon federal taxes in the same field.

The goal of the commission, the President said, was "to safeguard the objectives" of joint Federal-State programs "from the threat imposed by existing confusion and inefficiency."

On March 30, he sent a message to Congress on Federal Grants-in-Aid. He was seeking, he said, a way "of achieving a sounder relationship between Federal, State, and local governments." The present division of activities had developed over "a century and a half of piecemeal and often haphazard growth." In recent decades, this growth had "proceeded at a speed defying order and efficiency." Reacting to emergencies and expanding public needs, the Federal Government had launched one program after another, without ever taking time to consider the effects of these actions on "the basic structure of our Federal-State system of government."

The Federal Government had entered fields that the President felt were primarily the constitutional responsibility of local governments. More than 30 Federal grant-in-aid programs existed, involving Federal expenditures well over $2 billion a year. The result was "duplication and waste." The impact of Federal grant-in-aid programs on the States, he believed, had been especially profound. Whatever good they accomplished, they also complicated State finances and made it difficult for the States to provide funds for other important services.

The President believed that "strong, well-ordered State and local governments" are essential to the Federal system of government. Further, "Lines of authority must be clean and clear, the right areas of action for Federal and State government plainly defined."

While concerned about this "major national problem," he wanted to avoid any confusion about the purpose:

To reallocate certain of these activities between Federal and State governments, including their local subdivisions, is in no sense to lessen our concern for the objectives of these programs. On the contrary, these programs can be made more effective instruments serving the security and welfare of our citizens.

To address these issues, the President recommended that Congress pass legislation to establish a Commission on Governmental Functions and Fiscal Resources. The message explained the purpose:

The Commission should study and investigate all the activities in which Federal aid is extended to State and local governments, whether there is justification for Federal aid in all these fields, whether there is need for such aid in other fields. The whole question of Federal control of activities to which the Federal Government contributes must be thoroughly examined.

The matter of the adequacy of fiscal resources available to the various levels of government to discharge their proper functions must be carefully explored.

The President's message did not mention the Federal gas tax or the Federal-aid highway program, but both fell within the purpose of the message. The Federal-aid highway program, in fact, was the Federal Government's largest grant-in-aid program. Moreover, the gas tax had long been eyed by the Governors as falling under their jurisdiction. The Governors Conference had repeatedly adopted resolutions calling for the Federal Government to abandon the tax and drop most of the Federal-aid highway program.

Congress approved the President's request. Under Public Law 83-109, approved by the President on July 10, 1953, the Commission on Intergovernmental Relations was authorized to conduct the study of Federal-State relations. Meyer Kestnbaum, Special Assistant to the President, would head the 25-member Commission.

The Governors were right about one thing. President Eisenhower agreed with them about the need to shift the balance-at least in theory. But the Governors would soon find that he disagreed on one important aspect of the debate: highways.

Business Advisory Committee

Although President Eisenhower would not become fully engaged in a highway initiative until the Grand Plan speech in 1954, he acted on highway safety in July 1953 when he met in the Cabinet Room of the White House with 28 business leaders. He told the leaders that his goal was to save 17,000 lives and $1.25 billion a year by reducing accidents. According to an account in Transport Topics for August 3, 1953:

President Eisenhower told the group . . . he is tired of having three to four times as many persons killed a year on the highways as were killed in Korea. He said the history of efforts to save lives on the highway shows that when something is done on a coordinated basis the accident trend drops sharply.

The president said that something-a truce-had been done about saving lives in Korea and that there is good reason why something should be done about highway accidents.

The article added that Light B. Yost, Director of Field Operations for General Motors (GM), made clear that the modernization of roads, which he said was lagging at the time, would have to be an important element in the safety initiative. Highway modernization was not only an economic and military necessity, but would make a major contribution to highway safety.

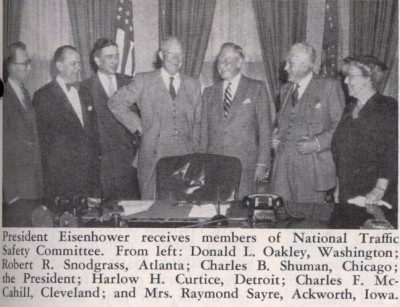

Based on the discussions during the meeting, the President appointed a 28-member Business Advisory Committee on Prevention of Motor Vehicle Accidents. The members were selected to represent agriculture, business, labor, women, public officials, organizations (such as service, fraternal, religious, and veterans), and media of public information. GM President Harlow H. Curtice, who had been unable to attend the White House meeting, chaired the Advisory Committee.

According to the BPR's annual report for 1954, the broad purpose of the committee "was to lend the prestige and interest of the President to the attainment of a traffic-safety organization in every community and to promote the effective community application of proved techniques for traffic safety." The BPR provided office space in its General Services Building headquarters as well as staff, printing, and supplies to support the committee.

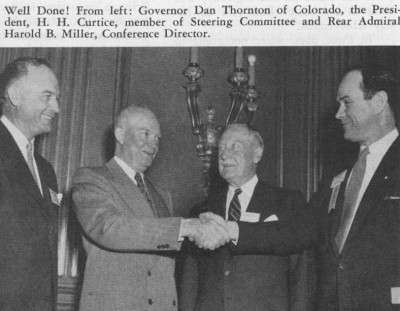

The President directed the Advisory Committee to hold a three-day Highway Safety Conference in Washington on February 17-19, 1954. The goal of the conference, according to Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks, was "to get an effective safety organization in every community from coast to coast." Secretary Weeks would serve as General Chairman of the White House Conference. Rear Admiral Harold Blaine Miller, USN (Retired), would serve as Conference Director. Miller, who had been the Navy Department's Director of Public Information until his retirement in 1946, held the same title with the American Petroleum Institute and was Executive Director of the Institute's Oil Information Committee. J. W. Bethea, Director of the National Committee for Traffic Safety, served as Admiral Miller's assistant. As with past conferences, the BPR provided staff support.

On December 11, 1953, the President wrote to the Nation's Governors to request their help:

Dear Governor:

The mounting toll of death and injury on our highways long ago reached a point of deep concern to all of us. It stands before America as a great challenge-humanitarian and economic-and must be met by urgent action.

I have examined the "Action Program for Highway Safety" which you and the other Governors have developed in cooperation with interested organizations and public officials having jurisdiction over highway safety. It is a sound and workable program, but effective citizen leadership is needed to help you put this great crusade into organized action on a scale far bigger than ever before.

Accordingly, I have called a Conference on Highway Safety for Washington next February seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth. The Conference will serve to focus more public attention on the problem and stimulate active leadership in every community.

I should appreciate your designating an appropriate group of your outstanding citizens as a delegation to represent your state. Since the Conference program will be built around seven basic groups-labor, agriculture, business, women, public officials, media of public information and other organizations (service, fraternal, religious, veterans, etc.), I would hope that your delegation will include representatives from each of these categories.

Will you please forward the names of your state's delegates to the Conference on Highway Safety, Room 1107, General Services Building, Washington 25, D.C. Secretary of Commerce Weeks, General Chairman, will send you detailed background information on the Conference shortly.

Naturally, we would be happy to have present all Governors whose schedules and responsibilities would permit attendance. At any rate, I am depending on your active cooperation and support to make this Conference more effective.

Sincerely,

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Federal Charter for the National Safety Council

While at the "Summer White House" in Denver, Colorado, President Eisenhower signed a bill on August 13, 1953, granting a Federal charter to the National Safety Council.

The Council had been formed in 1913 by industrialists on the theory that accidents of all types were preventable. Public Law 83-259 provided a charter to the Council as a nonpolitical organization that would not contribute to or assist any political party or candidate. The Council was one of several public service organizations, including the American Red Cross and the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, granted such charters.

As the Council pointed out, the charter did not grant Federal funds or make the organization part of the Federal Government. The Council would remain a privately financed and operated organization under the control of its directors and trustees. The charter, however, "bestows the prestige of governmental blessing" on the Council and "stamps the Council's four decades of work and its present stature and character with a seal of approval."

Ned H. Dearborn, the Council's President, said, "The new charter is a challenge to better work and greater effort. It offers wider opportunities. And with the help of all those who are now working hard for safety, such an effort cannot fail."

(The Council remains in operation in 2003. Its mission: "to educate and influence society to adopt safety, health and environmental policies, practices and procedures that prevent and mitigate human suffering and economic losses arising from preventable causes." Highway safety remains one of the Council's many concerns.)

White House Conference on Highway Safety

The White House Conference on Highway Safety was held in the Departmental Auditorium. The President was one of the first speakers to address the more than 3,000 delegates during the opening session on February 17, 1954. An account in Public Safety magazine said:

When President Eisenhower strode to the speaker's platform as the red-jacketed Marine Band struck up "Hail to the Chief," more than 3,000 delegates, packing every nook and cranny of the huge Departmental Auditorium stood up and applauded. Nine governors and Chief Justice [Earl] Warren of the United States Supreme Court flanked the President as he spoke.

After noting the privilege of addressing the conference, he began:

The purpose of your meeting is one that is essentially local or community in character. But when any particular activity in the United States takes 38,000 American lives in one year, it becomes a national problem of the first importance. Consequently, this meeting was called, and you have accepted the invitation, in an understanding between us that it is not merely a local or community problem. It is a problem for all of us, from the highest echelon of Government to the lowest echelon: a problem for every citizen, no matter what his station or his duty.

I was struck by a statistic that seemed to me shocking. In the last 50 years, the automobile has killed more people in the United States than we have had fatalities in all our wars: on all the battlefields of all the wars of the United States since its founding 177 years ago

He acknowledged that this was a problem that "by its nature has no easy solution." He did not intend to get into the technicalities of this "many-sided" problem. However, he felt that the key was public opinion. "In a democracy, public opinion is everything." He explained:

If there were community groups established that could command the respect and the support of every single citizen of that city or that community, so that the traffic policeman, so that everyone else that has a responsibility in this regard, will know that public opinion is behind him. Because I have now arrived at the only point that I think it worthwhile to try to express to you, because in all the technicalities of this thing you know much more than I do.

If, he said, "we can mobilize a sufficient public opinion, this problem, like all of those to which free men fall heir can be solved."

He had seen statistics indicating that in 1975, more than 80 million automobiles would be using the Nation's roads:

Now, the Federal Government is going to do its part in helping to build more highways and many other facilities to take care of those cars. But 80 million cars on our highways! I wonder how people will get to highway conferences to consider the control of highway traffic. It is going to be a job.

But that figure does mean this: we don't want to try to stop that many automobiles coming-I am sure Mr. Curtice doesn't anyway-we want them. They mean progress for our country. They mean greater convenience for a greater number of people, greater happiness, and greater standards of living. But we have got to learn to control the things that we must use ourselves, and not let them be a threat to our lives and to our loved ones.

He concluded by emphasizing the importance of mobilizing public opinion in the cause of highway safety. He thanked the delegates for attending and for participating in highway safety initiatives in their communities. "I think you are engaged in something-I know you are engaged in something that is not only to the welfare of every citizen of the United States, but I believe that they realize it."

According to Transport Topics, many delegates arrived late and missed the President's talk or saw it only on the four television sets stationed in the lobby:

Delegates to the White House Conference on Highway Safety came to grips with one of the great problems of their mission even before the meeting got underway. With 3,000 persons converging during the morning rush hour on Washington's Departmental Auditorium, where the general sessions were held, traffic snarls developed on the streets leading to the building, delaying some of the delegates.

Other speakers followed up on the President's themes of public opinion and public involvement. During the opening session, Secretary Weeks said that after 30 years of experience, "we know what the preventive measures are and how to apply them."

They were embodied in the Action Program "covering the fields of education, engineering, accident records, enforcement, motor vehicle administration, laws and ordinances, public information and public support." He added, "We will aim at the task of mobilizing widespread and intensive support for crucial parts of the program."

Governor Thornton, also speaking during the opening session, told the delegates:

To achieve and maintain peace on the highways, we don't need to organize the whole population, just those with the energy, interest, intelligence, and persistence to tackle the job and stick to it day after day, year after year, taking each new step as the next stepping stone becomes visible.

He added that, "neither peace among nations nor peace on the highways will come as a miracle. Each is a day-by-day achievement."

Chief Justice Warren discussed the problem from a legal perspective. "Traffic safety is a basic problem of American life," he said. After citing some of the problems caused by accidents, he explained:

Its solution calls for universal understanding of its magnitude and of the factors implicit in it, as well as a determination to eliminate the dangers to life and the economic losses occasioned by negligence, indifference and lawlessness.

One of the most important phases of the problem is the disposition of twelve million traffic cases annually in our traffic courts. Congestion of calendars, haphazard practices and the lack of well conceived programs of enforcement contribute greatly to our difficulties.

Secretary of Agriculture Ezra Taft Benson pointed out the importance of traffic safety to the farmer:

Farm residents suffer more fatal motor vehicle accidents than any other type of accident . . . . Farm production is vital to America's welfare-now and in the future. The huge waste of vital farm manpower and material resources caused by accidents must be stopped.

Robert B. Murray, Jr., Undersecretary of Commerce for Transportation, urged public officials to identify the "people and organizations already engaged in highway safety work. They will provide a most important asset in further awakening public opinion to the traffic safety problem."

Traffic safety experts, such as Franklin M. Kreml, also addressed the conference. Kreml was Director of the recently established Transportation Center at Northwestern University. He told the delegates that developing vigorous public support at the local level could save 20,000 lives and prevent 600,000 injuries a year:

Without organized citizen action, we cannot expect to get sound official action-by the police, courts, engineers, educators, and driver license authorities-and without that, we can't bring down the death toll.

While receiving the delegates' suggestions on the final day of the conference, Vice President Nixon acknowledged the seriousness of the problem. "It is more dangerous to go to work these days than it is to work." He appreciated the participation of citizens, saying, "this is a problem which must be solved on Main Street instead of Pennsylvania Avenue."

Public Safety magazine summarized the highlights of the White House Conference on Highway Safety:

- Every Governor is urged to call annual governor's conferences to mobilize safety efforts in the pattern of the White House meetings.

- The President and 48 governors are asked to proclaim a month-long safety campaign annually to promote public understanding and support of the accident prevention program.

- Business leaders pledge initiative in developing community support organizations for traffic safety.

- Labor gives assurance it will be more active in traffic safety by giving assistance on traffic commissions or boards, by affiliation with various civic and service clubs in the interest of carrying the community safety campaign to them, and by whatever service it can offer law enforcement agencies.

- Recommended that highway and police personnel be built up to minimum standards at least.

- Suggested that land grant colleges, with their extension and continuing education services, be used to extend traffic safety education, especially among farm groups, and that 4-H clubs, Future Farmers of America and other rural youth groups be included in the planning and action phases of all rural traffic safety programs.

- Media (Radio and TV, daily and weekly newspapers, magazines, outdoor advertising and motion pictures) offer approximately 50 specific moves designed to put all its forces-written, oral and visual-back of the President in launching the greatest "Crusade for Safety" in the nation's history-with every American asked to sign this safety pledge:

"I personally pledge myself to drive and walk safely and think in terms of safety.

"I pledge myself to work through my church, civic, business and labor groups to carry out the White House action program for highway safety.

"I give this pledge in seriousness and earnestness, having considered fully my obligation to protect my life and the lives of my family and my fellow man." - Women's groups pledge support to traffic law enforcement and cooperation with professional traffic safety people by study of inventory needs, offering local help in planning remedial programs.

- Recommended that safety education be expanded in elementary and high schools, including driving courses.

The President's Action Committee for Traffic Safety

During the conference, the Vice President announced that the President would form an Action Committee for Traffic Safety that would include the chairmen of the seven basic committees of the White House Conference on Highway Safety. The Committee met and was designated in the Oval Office of the White House on April 13, 1954. The original members were:

- Harlow H. Curtice, President, GMC, representing business;

- Raymond Leheney, Secretary-Treasurer, Union Label and Service Trades Department, American Federation of Labor, presenting labor;

- Michael J. Quill, President of the United Transportation Workers, Congress of Industrial Organizations, also representing labor;

- Charles F. McCahill, Senior Vice President, Forest City Publishing Company, Cleveland, Ohio, representing media of information;

- Charles B. Shuman, President of the Illinois Agricultural Association, representing agriculture;

- Robert B. Snodgrass, Vice President for local safety organizations of the National Safety Council, representing organizations;

- Mrs. Raymond Sayre of Iowa, past national President, Associated Countrywomen of America, representing women; and

- Governor Dan Thornton, representing public officials.

In a letter that same day to Curtice, the President explained that he did not want to lose the enthusiasm generated by the White House Conference on Traffic Safety. Therefore, he had decided "to have a national committee for traffic safety formed to follow through on the fine work begun by the business group."

During an organizational meeting, the members selected Admiral Miller as the volunteer director. GM's Yost was appointed secretary, while Bethea became the committee's staff director. Curtice secured private funds to pay Bethea's salary and expenses.

The President's Action Committee for Traffic Safety was, according to the BPR's 1954 annual report, "the first continuing action group ever created by Presidential appointment." The report summarized the purpose:

The group was established to coordinate activities of various autonomous national organizations in the traffic-safety field, and to promote effective citizen support, at the community level, for proven methods of improving street and highway safety.

They would, in short, provide a direct line of coordination from the White House to the grass roots efforts of the communities.

Labor Day, 1954

One of the National Safety Council's promotional activities was pre-holiday fatality predictions intended to alert drivers to the need for safe driving. For Labor Day 1954, the Council predicted 390 fatalities would occur during the holiday.

Just before the holiday, the President issued a statement on September 3, 1954, from the "Summer White House" at Lowry Air Force Base in Colorado regarding the Labor Day weekend:

A year ago, at this time, four hundred and five men, women and children, along with millions of other Americans, were looking forward to summer's last big outing-the Labor Day weekend. Three days later, these 405 were dead.

They died in holiday traffic accidents just as similar accidents had taken 480 lives the year before, and 461 the year before that.

I have just been given a grim forecast. The experts say that, over this Labor Day weekend, before our people go back to work on Tuesday, 390 people will lose their lives in this needless way.

Do we have to let this happen? Have we reached the point where we are helpless in the face of a prediction that almost four hundred of us will kill ourselves or someone else over a weekend?

To everyone who gets behind a steering wheel during the Labor Day weekend I make this appeal:

Let's be careful this weekend. Let's stay alert. Let's remember the simple rules of the road. Let's fool the experts. Let's all be alive next Tuesday.

After the holiday, Council President Dearborn sent a telegram to President Eisenhower:

I am sure you will be glad to know that Labor Day holiday traffic death toll of 364 was lowest for any Labor Day holiday since 1948. This was 26 below our pre-holiday estimate of 390 . . . .

We are sure that the emphasis given the need for greater highway safety over the holiday in your statement of last Friday, and the activities of the President's Action Committee for Traffic Safety, played a big part in the relatively low Labor Day toll. We also are sure that you and your Committee are helping importantly in focusing public attention on the need for day-by-day care, courtesy and common sense on the highway. While the Labor Day toll was still tragically high, we believe that taken in conjunction with the Fourth of July toll and the steady decline in traffic deaths month by month this year it reflects an increasing public awareness of the accident problem and the need for accident prevention.

Dearborn pledged the Council's full and complete cooperation with the President and the Committee "to see that the traffic toll keeps right on coming down.

President Eisenhower replied by telegram:

I deeply appreciate your telegram. No American can take satisfaction in a traffic death toll still so tragically high.

That we lost 26 fewer Americans than experts expected would die in accidents over last weekend should mean to us only that we now have proof that we can, if only we will, largely eliminate this monstrous daily slaughter on the Nation's roads and highways. To that objective I know every responsible citizen will continue to devote himself.

I am delighted to have your powerful statement on behalf of the National Safety Council reiterating its determination to forge steadily ahead in this field.

Safe Driving Day

One of the activities that emerged from the conference was an annual Safe Driving (S-D) Day. Under the concept, the President would ask each Governor to proclaim the day and to appoint State S-D directors. In turn, the Governors would ask each community to appoint a local director.

S-D Day would be preceded by 10 days of intensive education through all channels of communication to alert the public to S-D Day and encourage the support of every individual in the effort. The National Safety Council prepared materials, such as a booklet titled What You Can Do to Make S-D Day a Success, to distribute in advance of the day. As Public Safety magazine put it, the idea was to "demonstrate traffic accidents can be reduced materially when all drivers and pedestrians fulfill their moral and civic responsibilities."

The first S-D Day was Wednesday, December 15, 1954. President Eisenhower played a key part in increasing public awareness. He asked Governor Thornton to "enlist the support of all the Governors" for S-D Day. Working with Governor Robert F. Kennon of Louisiana, chairman of the Governor's Conference, Governor Thornton asked each Governor to take three actions:

- Designate a State S-D director to head up the program on a statewide basis.

- Call upon all mayors and county officials to enlist in the program, asking each to designate a local S-D director.

- Issue an official proclamation on November 15 designating December 15 as S-D Day, and calling on all organizations to develop definite activity to effectuate the program.

On November 16, President Eisenhower issued a statement about S-D Day:

My fellow citizens:

December 15th this year will be Safe Driving Day-a day proclaimed throughout America by your governors, mayors and county officials in cooperation with the President's Action Committee for Traffic Safety. This Committee is a volunteer group of citizens working, at my request, to reduce fatalities and accidents on our nation's streets and highways.

All of us agree with the purpose of Safe Driving Day. It is to save lives and to prevent injuries. No endeavor could be more worthy of our universal cooperation. None is more urgent.

On this December fifteenth I hope that every American will help make it a day without a single traffic accident throughout our entire country.

How can we best do this? Three things are essential.

First, let's each of us make sure that we obey traffic regulations.

Second, let's follow common sense rules of good sportsmanship and courtesy.

Third, let's each one of us resolve that, either as drivers or as pedestrians, we will stay alert and careful, mindful of the constant possibility of accidents caused by negligence.

If every one of us will do these three things, Safe Driving Day can be a day without a traffic accident in all of America.

Last year, when I called a national conference on highway safety, Americans were being killed in traffic accidents at the rate of 38,000 a year. A million more were being injured.

This year, although we are driving more cars more miles than ever before, the number of deaths and injuries is smaller. Clearly, we have found that it is not necessary to have more and more deaths and injuries.

I believe we can do even better-and that we must do better. Each of us must help.

Won't you do your part on December fifteenth to help stop death and injury on the highways and roads of America? Let's make Safe Driving Day an overwhelming success, and our nation's standard for the future.

His comment on 1954 fatalities was a reference to the fact that traffic deaths had dropped in October 1954 for the 10th month in a row, compared with the same month in 1953.

On December 8, he began his press conference with an appeal for public support:

I have designated December 15 as Safe Driving Day, and I have got a tremendous conviction the United States can do anything it wants to. I would like to get you to transmit requests to all your bosses-editors and the publishers and everybody else, the people that run the radio and television and telenews, and everything. Let's get safe driving in the headlines and prominent places on December 14th and 15th, and see what a record we can make for December 15.

He added, "This is, I say, a request, and it is not trying to tell anybody his business."

He filmed a message on December 14, again calling on the Nation to walk and drive cautiously:

At the request of the Governors and other officials, I have designated tomorrow, December 15, as Safe Driving Day.

I have a deep conviction that the United States can do anything to which 160 million citizens set their hearts and minds. If we are determined to have a day without a traffic accident in all of America, we can have it.

So let us see how many highway deaths and injuries we can prevent by obeying traffic regulations, following simple rules of good sportsmanship and courtesy, and staying alert and careful-whether we are driving or walking.

Let us establish an unblemished record of safety on Safe Driving Day, and then make that record our standard for the future.

On S-D Day, December 15, he started a news conference by saying, "Good Morning. I suppose you would expect me to mention that this is Safe Driving Day, and I am really hoping for the very best." He said he had been notified that a petition was "on the way to my desk, somewhere in the mailroom," from 20,000 people from one city offering their cooperation. "I hope it is certainly effective, not only in that city but everywhere."

The results were not as dramatic as had been hoped. On the comparable Wednesday in 1953 (December 16), 60 people were killed and 1,807 people were injured on the Nation's highway in 4,907 crashes. On the first S-D Day in 1954, 51 people were killed and 966 were injured in 3,935 crashes.

An editorial in Public Safety magazine asked if all the effort put into S-D Day had been worthwhile. After citing the statistics, the editorial stated:

Were these nine lives worth all the trouble and shouting? They were if one of them happened to be yours-or that of someone you love!

And the S-D Day bonus went far beyond those nine lives. It benefited several hundred people who would have been injured in traffic accidents on S-D Day had the toll been normal instead of below normal.

And think what the lowered S-D Day toll meant to the thousands of drivers who were spared dented fenders or worse from minor accidents that might have happened that day but didn't!

And if the nine lives saved still seem pathetically few in terms of the big build-up, just extend that 17.5 per cent saving to the entire year of 1954. If the reduction effected on S-D Day could have prevailed every day of 1954, more than 6,000 lives would have been saved!

The editorial concluded by answering its own question: "What about S-D Day? In our considered judgment, it was tremendously worthwhile."

An accompanying article observed:

One thing is certain-there were few, if any, people in the United States who didn't know that S-D Day was going to be observed on Wednesday, December 15, and that every man, woman and child throughout America was expected to play his or her part in making the day a success.

Overall, traffic deaths declined from 38,300 in 1953 to 36,300 in 1954-a drop of 5 percent. It was the lowest total since 1950 despite a 20-percent increase in motor vehicle mileage. The fatality rate had been 6.5 deaths per 100 million vehicle miles, down from 7.1 in 1953 (and 7.6 in 1950). However, the string of monthly reductions had come to a halt in November when fatalities were slightly higher than in November 1953. Fatalities in December 1954 were again below December 1953 (3,730 in 1954 compared with 3,920 in 1953).

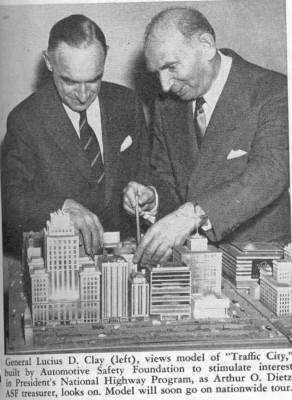

Congress Considers the Grand Plan

Following Vice President Nixon's announcement of the President's Grand Plan for highway improvement on July 12, 1954, the Nation's Governors formed a committee to work with the President's Advisory Committee on a National Highway Program, headed by retired General Lucius D. Clay, a close friend and advisor of the President. The goal was to develop recommendations for transmittal to Congress to use in developing legislation to implement the President's vision. Working with the Governors' committee, the Clay Committee developed a plan to finance construction of the Interstate System. The Federal Government would issue bonds to pay for construction over a 10-year period and use revenue from the Federal excise tax on gasoline to retire the bonds.

President Eisenhower submitted the plan to Congress on February 22, 1955. After explaining how the proposal came about, the President's transmittal letter cited the "inescapable evidence that action, comprehensive and quick and forward-looking, is needed." He listed four points, beginning with:

First. Each year, more than 36,000 people are killed and more than a million injured on the highways. To the home where the tragic aftermath of an accident on an unsafe road is a gap in the family circle, the monetary worth of preventing that death cannot be reckoned. But reliable estimates place the economic cost of the highway accident toll to the Nation at more than $4.3 billion a year.

The other points were the costs resulting from the poor condition of the road net, the inadequacy of the road net if cities had to be evacuated in advance of an atomic attack, and the increasing cost of congestion as traffic grows.

The President endorsed the Clay Committee's recommendations for financing construction of the Interstate System and other highways, but he recognized that "the vastness of the highway enterprise fosters varieties of proposals which must be resolved into a national highway pattern." Nevertheless, he said, the Clay Committee's report and a pending BPR report on highway needs "should generate recognition of the urgency that presses upon us; approval of a general program that will give us a modern safe highway system; realization of the rewards for prompt and comprehensive action. They provide a solid foundation for a sound program."

The Clay Committee's report, A Ten-Year National Highway Program, described the deficiencies of the Nation's highways in detail. Turning to the safety problem, the report stated that "the safety factor must assume large importance." The report quoted the President's comment that the annual death toll was "comparable to the casualties of a bloody war, beyond calculation in dollar terms." The report also quoted a report by the Governors' highway committee:

A simple dollar standard will not measure the "savings" that might be secured if our highways were designed to promote maximum safety, so that lives were not lost and injuries sustained in accidents caused by unsafe highways . . . . But whatever the potential saving in life and limb may be, it lends special urgency to the design and construction of an improved highway network.

Upgrading the Nation's highways would be an important element in the effort to reduce accidents, as the Clay Committee's report explained:

Replacement of the obsolete and dangerous highway facilities which contribute to this tragic condition with roads of modern design will substantially reduce this toll. The death rate on high-type, heavily traveled arteries with modern design, including control of access, is only a fourth to a half as high as it is on less-adequate highways. The average motorist today will undoubtedly be surprised to learn that he pays considerably more for insurance to protect himself against accident costs than he pays in State fuel tax and license fees which supply almost the entire financial support for the streets and highways over which he operates.

The President's proposal received a mixed reaction in Congress. Although support for the Interstate System and other highway improvements was widespread, the financing mechanism conceived by the Clay Committee was widely derided. Even Republican leaders in Congress gave only token support to the concept. As a result, the President's expectation that action would occur in 1955 would be frustrated. The Senate approved a bill introduced by Senator Albert Gore, Sr. (D-Tn.), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads, that differed from the President's bill in many respects. It was silent on financing because under the Constitution, the House of Representatives initiates tax legislation.

Opposition from highway interests that wanted the Interstate System but did not want to pay for its construction resulted in defeat of the President's proposal in the House on July 27, 1955. Moments later, the House also rejected an alternative developed by Representative George Fallon (D-Md.), Chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads, based on increasing the gas tax to finance construction on a pay-as-you-go basis. The giant road bill that everyone wanted was dead for the year.

The next day, the President issued a statement expressing his deep disappointment about the House's action:

The nation badly needs new highways. The good of our people, of our economy and of our defense, requires that construction of these highways be undertaken at once.

There is difference of conviction, I realize, over means of financing this construction. I have proposed one plan of financing which I consider to be sound. Others have proposed other methods. Adequate financing there must be, but contention over the method should not be permitted to deny our people these critically needed roads.

He expressed hope that Congress would reconsider the matter, but that was not to be in 1955. Congress adjourned without taking further action on the President's Grand Plan.

Facing up to the Problem

In June 1955, Rear Admiral Miller reported on the progress of the President's Action Committee for Traffic Safety. He saw encouraging signs that "we are facing up to the seriousness of the problem and are doing something about it." In particular, the report explained that traffic deaths had declined by 2,000 from 1953 (38,300) to 1954 (36,300). This 5-percent reduction in deaths, the report stated, was the first reduction since 1949 and the first continuous downward trend since World War II.

From its inception, the Action Committee had focused on encouraging the activities of existing national, State, and local organizations to develop a favorable climate in which these agencies and officials could operate most effectively. The goal was community application of the known techniques of traffic safety. To this end, the Action Committee had published a brochure titled Organize Your Community for Traffic Safety. It contained case histories of successful community and State programs, along with the recommendations emerging from the White House Conference on Highway Safety.

Therefore, another positive sign was the fact that 250 communities over 100,000 population had organized or made substantial improvement in their safety organizations in 1954. Still, only 114 of the 1,399 communities over 10,000 population had effective safety organizations. Admiral Miller said:

Our hope for a continued reduction in the traffic-accident toll rests on community effort. An effective community traffic-safety program can best be assured through a continuing citizens' organization which will mobilize public opinion in support of the officials' responsible for traffic and safety. It is in this area that we must concentrate our effort in the months ahead.

He added, "So our job is cut out for us if we are to achieve President Eisenhower's goal of an effective traffic safety organization in every community."

A decision was pending on whether to hold another S-D Day. The associations that had participated in S-D Day 1954 were enthusiastic about holding a similar campaign, according to the Action Committee's report, which stated:

The primary purpose of the campaign was not simply a single day of attention to safe driving, but rather an effort to focus public attention on the need for year-around safe driving and walking. Safety people are generally agreed that such emphasis was effectively given, and that their own continuing programs have benefited.

Admiral Miller explained that the Action Committee and the associations were considering modifications for S-D Day 1955. "We may attempt, for example, to 'keep score' for a period of 10 days on either side of S-D Day (proposed for December 1), thus providing a three-week period in which to measure the effectiveness of the program."

Overall, the Action Committee had identified two fundamental objectives for the year ahead:

- further broadening and refinement of the committee's efforts to stimulate effective community action, and

- further development of liaison with other traffic-safety agencies.

To help achieve these goals, the President's Action Committee for Traffic Safety established an Advisory Council including the principal executive officers of national organizations with recognized highway safety programs. Although the Advisory Council would not have a fixed number of members, the initial membership was 21 individuals. Harlow Curtice explained the purpose of the Advisory Council:

The Council will be able to serve effectively in initiating proposals for action to improve highway safety, and will act also as a clearing house and appraisal body for technical ideas submitted to the President's Committee.

The Committee will look to the Council for recommendations regarding national special emphasis programs and research needs in the traffic safety field.

Curtice asked William Randolph Hearst, Jr., editor-in-chief of the Hearst newspaper chain, to serve as chairman of the Advisory Council in recognition of his "constructive leadership" in the area of highway safety. The President wrote to Hearst on June 17, 1955, to thank him for his willingness to serve as Chairman of the Advisory Council to the Committee for Traffic Safety:

It is gratifying to know that you will be turning your interest and broad experience in traffic problems to the urgent traffic safety program.

In extension of this, I should like to ask you, as Chairman of the Advisory Council, to serve also as an ex officio member of the Committee. By doing so, you can contribute significantly to strengthened Committee liaison with the national highway safety organizations represented on the Advisory Council. I need not emphasize to you the importance of a close tie between the two groups.

Hearst, who agreed to serve on the Action Committee, was a logical recruit to the President's crusade. In October 1952, Hearst had launched The Hearst Newspapers' Campaign for Better Roads. Hearst later said that, "We saw it as our job to explain the problem to our readers and to get them to demand and support an adequate highway construction program, nationally and locally."

"We missed no opportunity," Hearst said, "to keep the story in front of our readers." The tireless drumbeat of news on the Nation's road situation included page 1 stories, editorials, cartoons, interviews, photographs, charts, and graphs. Between October 1952 and the end of 1955, the Hearst Newspapers printed nearly 3 million lines on the highway problem-enough to fill an average-size metropolitan daily newspaper for 76 straight days.

Safety was an important element of the highway campaign. Following the White House Conference on Highway Safety, Hearst had published an editorial in the Chicago Sunday American and 14 other Hearst newspapers on February 21, 1954. He began:

If the cure for a disease that killed 38,000 and maimed, crippled or injured 1,330,000 others were suddenly discovered, it would be Page One News in every publication in the land.

Or if in the Korean fighting we had 38,000 killed in action and another 1,330,000 wounded, there would have been a nationwide demand for an end to that kind of bloodletting unless, of course, it was leading to definite military results.

And yet, these are the shocking statistics of the toll taken each year and we accept them with a complacency unbecoming to us.

The figures weigh heavily on my mind at the moment because for the past three days I have been attending the White House conference on highway safety in Washington which President Eisenhower addressed Wednesday. Having rejected two prepared speeches, the president talked off the cuff and from the heart, which is when he is at his best.

Representing New York media of information, Hearst found the assignment a "very engrossing and challenging affair." He came away encouraged:

This is a disease for which there is already a serum. The research has already been done and the cure is known. In a few communities the treatment has been applied and the cure accomplished. The job now is to get the serum to every state, county, and community in this country.

The delegates were dedicated to the cause and would "go back to their home towns and get to work immediately to cut the traffic toll by 40 percent." He added, "As I understand it, the men and women gathered here are convinced that the kidding is all over." They would "set up permanent, competently staffed organizations that will use the techniques already tested."

One of those techniques was "rigid enforcement of correct laws." For too long, Hearst said, Americans had tolerated inadequate traffic laws and loose enforcement because "we have a typical American sympathy for a man who is in trouble because of something he did wrong on the highways." Juries didn't like to convict motorists of criminal negligence or homicide because the members felt "there but for the grace of God, go I." Hearst was convinced these attitudes must change:

Yet, unless our laws, our highway rules, are enforced right down the line we are not going to save those 15,000 American men, women, and children.

This is the sort of thing that is going to be done, that must be done, and your part and mine is to understand the necessity for it and cooperate.

The Hearst Newspapers last week editorially pledged themselves to do everything in their power to make this life-saving campaign successful. Today I wish to repeat that pledge personally in this column of mine.

I said the delegates here were deadly serious about this problem. I think we all are, really. So let's get to work, and lick it once and for all.

Commission on Intergovernmental Relations

The Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, established in 1953 to study Federal-State relations, completed its work in June 1955 with a report to President Eisenhower. He transmitted the report to Congress on June 28. His cover letter pointed out that 168 years earlier, the Founding Fathers had designed the Federal form of government "in response to the baffling and eminently practical problem of creating unity among the thirteen States where union seemed impossible." Since then, the Federal structure had been "adapted successfully" until recent years:

In our time, however, a decade of economic crisis followed by a decade of war and international crises vastly altered federal relationships. Consequently, it is highly desirable to examine in comprehensive fashion the present-day requirements of a workable federalism.

Given the "intricate interrelationship of national, state, and local governments," the President told the Congress that "it is important that we review the existing allocation of responsibilities, with a view to making the most effective utilization of our total governmental resources." He urged Congress to study the recommendations of the Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, "the first official body appointed to study and report on the general relationship of the National Government to the States and their local units." To the extent that the recommendations entailed action by the Executive Branch, the President pledged to "see that they are given the most careful consideration."

The Commission, in examining elements of government, had established a Study Committee on Federal Aid to Highways, one of the perennial points of dispute between the Federal and State governments. The members were:

Clement D. Johnston, Chairman of the Study Committee and President, Chamber of Commerce of the United States.

Governor Allan Shivers of Texas.

Frederick P. Champ, President, Cache Valley Banking Company, Logan, Utah.

Randolph Collier, State Senator, Yreka, California.

William J. Cox, former State Highway Commissioner of Connecticut.

Dane G. Hansen, President, Hansen Lumber Company, Logan, Kansas.

Major General Frank Merrill, Commissioner of Highways, New Hampshire.

Robert B. Murray, Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation.

J. Stephen Watkins, President, J. Stephen Watkins Engineering Company, Lexington, Kentucky.

On June 20, 1955, Chairman Kestnbaum submitted the Study Committee's report to the President. The Study Committee agreed about the need for better roads, but its report said "the real issue is not whether we should have better highways, it is how best to get them."

The Study Committee believed that highways served different purposes and should be treated accordingly in sorting out Federal-State relationships. The greatest national responsibility for highways centered on expeditious development of the National System of Interstate Highways. The Study Committee rejected the idea that the Federal Government should build and operate the Interstate System; it recommended "concentration of Federal funds on construction of the Interstate System, together with State participation."

Substantial Federal financial support was essential, with the States bearing "not less than one-half of the construction costs." Toll financing could pay for about one-third of the Interstate System, but beyond that mileage, the Federal Government should provide Federal-aid sufficient "to accomplish its improvement at a rate commensurate with the national welfare and should be allocated in such a way as to give highest priority to correction of the most serious deficiencies."

For other roads, the Study Committee recommended eliminating Federal participation over time. The States could be counted on to address needs off the Interstate System because "the failure of any State or locality to provide adequate highways brings its own prompt and automatic penalties upon the areas involved." States would act in "their own intelligent self-interest" to provide adequate highways "when they understand the responsibility is theirs."

The Study Committee endorsed elimination of the Federal gas tax, a goal long sought by the States. The States, the Study Committee concluded, "have demonstrated ability to tax motor fuels effectively and economically." Repealing the Federal tax would give the States a potential tax increase of more than $800 million a year, assuming they increased State taxes by the same amount as the abandoned Federal tax.

At the same time, the Study Committee recommended "without qualification" the continuation of the BPR:

The Bureau should continue to conduct and integrate basic highway research, disseminate the results of research, assemble and collate statistics, and provide technical assistance to the States and their subdivisions.

The BPR also should help plan and stimulate "the articulated network of highways necessary to serve the Nation's productive and defensive strength." Moreover, it should help stimulate highway programs "to promote economic stabilization when appropriate." However, the report recommended that the BPR "substantially reduce most of the present close supervision and inspection of State highway activities."

In transmitting the Study Committee's report to the President, Kestnbaum noted that the report had been considered by the Commission, but that the Commission "arrived at its own findings and recommendations." Actually, the Commission rejected many of the Study Committee's recommendations. On the most basic issue of the Federal role, the Commission's report said:

The Commission believes that there is sound justification for federal participation in the improvement of many highways. The Commission generally approves existing legislation, which provides federal aid for primary highways, including interstate routes and urban extensions, and for secondary roads, including farm-to-market roads.

The Commission observed that the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954 had increased the Federal-aid highway program significantly:

However, there is abundant evidence that the current rate of highway improvement is not sufficient to meet current emerging demands. Failure to meet these needs will seriously affect the national security and the national economy. Humanitarian considerations alone, in terms of reducing the annual toll of highway accidents, call for vigorous action in revamping the unsafe segments of the highway network.

To finance the expanded program, the Commission had been divided, with four members of the 25-member Commission recommending bonds to pay for the Federal financing. The remaining members, including the 10 Members of Congress who served on the Commission, disagreed. The Commission's report stated:

The Commission recommends that the expanded highway program be financed substantially on a pay-as-you-go basis and that Congress provide additional revenues for this purpose, primarily from increased motor fuel taxes.

The increased tax revenue was justified:

- to give recognition to the national responsibility for highways of major importance to the national security, including special needs for civil defense, and

- to provide for accelerated improvement of highways in order to insure a balanced program to serve the needs of our expanded economy.

As for the bonds favored by the President as a financing mechanism for the Interstate System:

An increase in taxes is preferable to deficit financing as a means of supporting larger highway outlays by the national government. The latter method would result in high interest charges and would shift the burden to citizens of a future generation, who will have continuing highway and other governmental responsibility of their own to finance.

The Commission supported toll roads as a State and local prerogative, but opposed Federal-aid in development of toll roads.

The Commission supported continuation of the BPR:

Over the years, the Bureau of Public Roads has made a notable contribution to highway improvement through technical leadership and the stimulation and coordination of State activity in this field. However, in the light of the maturity and competence of most State highway departments, it appears to the Commission that the Bureau of Public Roads could relax most of its close supervision of State highway work.

On August 2, Congress adjourned for 1955, shortly after the President transmitted the Commission's report for consideration.

Safe Driving Day, 1955

On August 5, President Eisenhower agreed to participate in S-D Day 1955. He wrote to Curtice to let him know that, "I am in accord with the determination of your Committee to broaden its work in stimulating effective community action throughout the country." He noted that his Special Message on Highways in February had been motivated "in large part" by the urgent need for improved highways to save lives." As a result, "In the hope that we shall be able to insure the safety of our families and fellow citizens, I shall be happy to participate in a safety campaign beginning on November 20, 1955, and culminating in S-D Day on December 1."

A national broadcast by the President on November 20 was to launch an intensive 10-day campaign on the theme: "Make Every Day S-D Day." A massive campaign was planned for the 10 days before S-D Day, through all channels of communication, to implant the theme in the public mind.

The National Safety Council's booklet What You Can Do To Make S-D Day a Success was provided to businesses, industry, civic groups and government agencies, as well as truckers, insurance companies, and colleges and universities. Advance efforts included publicity releases sent to 6,500 newspapers around the country, and a series of 100-line newspaper ads. In addition, the American Automobile Association distributed posters, bumper stickers, placards for school safety patrols, and other materials through its 750 affiliated motor clubs and branches.

On September 24, the 65-year-old President suffered a heart attack while vacationing in Fraser, Colorado. As a result, he was unable to participate directly in the 1955 campaign. Putting the best face on the situation, Public Safety suggested that, "In view of the President's intense interest in traffic safety and his inability to lead the campaign personally, most observers believe the American public will rally in greater numbers than ever before to this S-D Day program."

As S-D Day approached, safety experts knew that the safety record for 1955 was going to be worse than in 1954. October was the eighth consecutive month in which motor vehicle deaths exceeded those in the same month the previous year. The total for the 10 months was 30,980 deaths, compared with 29,080 during the first 10 months of 1954. H. Gene Miller, Director of the National Safety Council's Statistics Division, pointed out in his monthly Public Safety article, that because of "zooming motor vehicle mileage," the fatality rate dropped to 6.0 during this period. However, this reduction "affords but little comfort in the face of the increased death total."

Although the President was unable to appear in the planned televised address 10 days before S-D Day 1955, he issued a statement on November 30 from his home in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania:

All over the United States tomorrow, Americans will join in a great National effort to save lives. The occasion will be the second nationwide "S-D Day"-Safe Driving Day.

The immediate objective of S-D Day is to have twenty-four hours without a single traffic accident. The long-range, and more important objective is to impress upon all of us the necessity for safe driving and safe walking every day of the year.

The need is obvious and urgent. Last year, an American man, woman or child was killed in traffic every fifteen minutes. Someone was injured every twenty-five seconds. And, this year, the record is worse: More people are dying; more are injured and crippled.

This tragic situation concerns every State, every community, every American. Actual experience has demonstrated that traffic accidents can be greatly reduced by proven, year-round safety programs, when these programs have year-round public support.

S-D Day is directed to the development of that kind of support. Literally millions of Americans are participating, through local, state and national organizations, cooperating with the President's Committee for Traffic Safety. This is a volunteer group, appointed by me, to stimulate permanent, effective safety programs in every community.

We know that we cannot solve the traffic accident problem in one day, but we can-and must-start doing a better job.

I appeal, then, to every American to help demonstrate tomorrow that we can-by our own, personal efforts-reduce accidents on our streets and highways. Having shown that we can do so on one day, let us all, as good citizens, accept our responsibility for safety every day in the future.

On S-D Day, December 1, 1955, 89 people were killed on the Nation's highways; on the comparable day in 1954, fatalities totaled 81. Although, according to Miller, deaths during the 21-day S-D Day period were lower than in 1954, "Not even the impact of S-D Day could halt the sharply higher monthly totals." The S-D Day month of December saw a 12-percent increase over the previous year (3,960 motor vehicle deaths compared with 3,530).

The results prompted Goley D. Sontheimer, Director of Safety Activities for the American Trucking Associations, to write in Transport Topics about the "apathy of the general public to the appeals, the information and the urging of radio, television and the newspapers." He suspected that hundreds of those who had promoted S-D Day had "thrown up their hands and have given up the fight from an educational standpoint."

Sontheimer speculated that the failure of S-D Day would be a panic that would turn to enforcement at all costs as the answer. "Failure can be laid almost directly to the panic approach-the lack of calm orderly thinking which will strike at the root of the problem." Of the Nation's 70 million licensed drivers, "it is highly probable that at least 20 million of them couldn't pass a driving skill test to save their licenses." Chronic violators comprised about 15 percent of drivers. Sontheimer suggested a solution to the problem posed by "these millions of drivers who are accidents-going-some-place-to-happen":

Rigid driver licensing laws would eliminate most of them if that licensing included periodical re-examination instead of periodical renewal. This with the point system in use for suspension and revocation purposes would go a long way towards solving our problem.

Overall in 1955, fatalities totaled 38,300, compared with the revised final total of 35,586 in 1954. The fatality rate was 6.4 in 1955 (6.3 in 1954). In fact, the toll was the highest since 1941, when 39,969 people were killed on the Nation's highways.

New approaches would be needed to confront what Public Safety called a "national disgrace."

Auto Safety Features, 1956

The September 1955 issue of Public Safety described some of the safety features of the automobile industry's 1956 models. As was the custom, the new cars were "under wraps" until they were revealed in an advertising and publicity blitz in September, but many of the safety features were known when the magazine was prepared.

American Motors Corporation: The Hudson and Nash featured "body construction of the shock-absorbing type," Meade F. Moore, vice president of automotive research and engineering, told the magazine. The new cars would not include seat belts. Moore explained that the company had included seat belts in its 1949 models. "However, the public did not accept them, claiming that seat belts were a 'nuisance' in ordinary driving."

Chrysler Corporation: The company stressed its rotary door latches to prevent doors from opening in a crash. The latches included an automatic "take-up" feature "so that the motion of the car always tends to tighten the latches for safety and silence." Chrysler engineers had developed seat belts that met the functional specifications of the Civil Aeronautics Administration for commercial airlines. The seat belts were available for installation in all Chrysler-made cars.

General Motors Corporation: Buick Division would offer seat belts as optional equipment, but would call them "safety belts." Ivan Wiles, Division General Manager, expressed doubts, however, about how much protection they would afford motorists. Oldsmobile would retain the safety-padded instrument panel it had used in 1955. (Additional information was not available.)

Studebaker-Packard Corporation: The company was proud of its new door latch with interlocking lip to prevent separation from the center post.

Ford Motor Company: Ford had decided to make safety its theme for 1956 (as described in the October 1955 issue of Public Safety). All Ford cars for 1956 would include a five-part safety package. Known as Ford's Life Guard Design, the package included a deep-center safety steering wheel "which slowly gives way under crash impact," double-grip rotor-type door locks, optional seat belts that can be anchored to the vehicle with a steel plate, crash cushioning for instrument panels and sun visors, and safety rear-view mirrors with plastic backing to reduce the possibility of glass falling out when shattered.

In summarizing the safety features, the September 1955 article in Public Safety stated that of the three factors in traffic-the vehicle, the roadway and the driver-much progress had been made in the first two. "Today's car reflects the continuing study of a competitive industry." Many new features would reduce the seriousness of injury in an accident:

In the final analysis, however, a complete solution of the motor vehicle accident problem rests with the individual-the driver as well as the pedestrian.

National Safety Forum and Crash Demonstration

On September 7-8, 1955, Ford had sponsored the first National Safety Forum and Crash Demonstration in Detroit and Dearborn, Michigan. The October 1955 issue of Public Safety reported that 150 specialists in traffic control and accident prevention attended the event.

The first morning included panel reports. The first was by John O. Moore, Director of Automotive Crash Injury Research at Cornell University Medical College. The magazine described Moore's presentation:

Moore traced the Cornell crash injury project back to the time, 13 years ago, when Hugh DeHaven, an expert in aviation design, began a study of why some people are killed and others virtually unscathed in falls from considerable heights.

DeHaven set forth two basic conclusions: First, those who survived such falls "struck in a position that spread the force of the fall over a large body area, and secondly, their fall ended in an environment which would bend or deform-which would yield to the impact, and in yielding would absorb force."

These conclusions led researchers into the field of forces as applied to occupants of an automobile which is involved in a crash. And, as the Cornell Specialist summarized, to these two conclusions.

- "Occupants of a car are approximately twice as safe in case of accident if they remain in the car-hence cars would be safer if equipped with seat belts and safety door latches.

- "When they remain in the car, they should have the advantage of crash padding on the 'danger spots' such as instrument panels, and of energy-absorbing steering wheels to keep the driver from being seriously injured when thrust against the steering column hub."

Lt. Col. John P. Stapp, Chief of the Aero Medical Field Laboratory at Holloman Air Force Base, described his crash research and reported that the automobile manufacturers were conducting similar crash tests. The magazine summarized:

All this effort, he said, is based on the experimentally demonstrated fact that the human body can survive the forces uninjured if it is properly shock mounted in a non-collapsing enclosure.

Finally, A. L. Haynes, Executive Engineer of Product Study for the Ford Engineering staff, described Ford's 2-year crash test program and showed how it resulted in the development of safety features.

That afternoon, Henry Ford II, President of the Company, presented a check for $200,000 to the Cornell Crash Injury Project. The check would cover one-third of the program's cost, with Chrysler Corporation and the Federal Government providing the balance.

The second day involved crash testing of four new Fairlanes in consecutive two-car collisions. Test dummies, known as Ferds (for Ford Engineering Research Department), were used to simulate human actions in the crashes. Guests were then shown Ford's Life Guard Design features for its 1956 cars.

As the forum ended with a luncheon in Lovett Hall at Ford's Greenfield Village, Benson Ford announced that the company did not consider these devices as "competitive sales secrets." Specifications were available to any automobile company that wanted them:

I want to point out that gathering this information has taken a lot of diligent and devoted effort at considerable expense. But we want to give this knowledge away to anybody that can use it. We hope other companies will take it, we hope they will use it and, if they can, improve upon it. This is one kind of competition we want to help out.

Ford intended to be as competitive in the field of automotive safety as it was in other areas:

I think if we can get this hard-hitting automobile industry to fight for safety leadership, we can achieve some really wonderful results.

The competition did not develop. Robert Lacey, in Ford: The Men and the Machine (Little, Brown and Company, 1986, p. 506) explained that Ford's safety campaign was "a disaster." Motorists concluded that the cars had so many safety features because they were more likely to crash than other cars. Lacey said:

Car advertisements are supposed to promote love, life, and a fast getaway from the traffic lights. Ford's attempts to persuade customers that the purchase of a Ford could save them from a grisly death had the very opposite effect. Ford sales slumped and Chevrolet widened its sales advantage that year by nearly 300 percent.

This lesson, summarized as "Ford sold safety and Chevy sold cars," coupled with American Motors' experience with seat belts in 1949, would be retold many times in coming years.

Man of the Year