A Moment in Time: Highway Safety Breakthrough

Richard Weingroff / FHWA News 2021

Until the 1960s, efforts to make highways safer had focused on two of the three keys in highway crashes: the road and the driver. The third element was the motor vehicle. For decades, the auto industry had supported efforts to make roads safer and drivers more skilled, while making vehicles bigger, more powerful, and faster. With a product to sell, the industry focused on what helped sales – and safety, in the industry’s view, was a sales dud. The Federal Government was unwilling to tell private companies what to do, but that attitude changed at a moment in time on September 9, 1966.

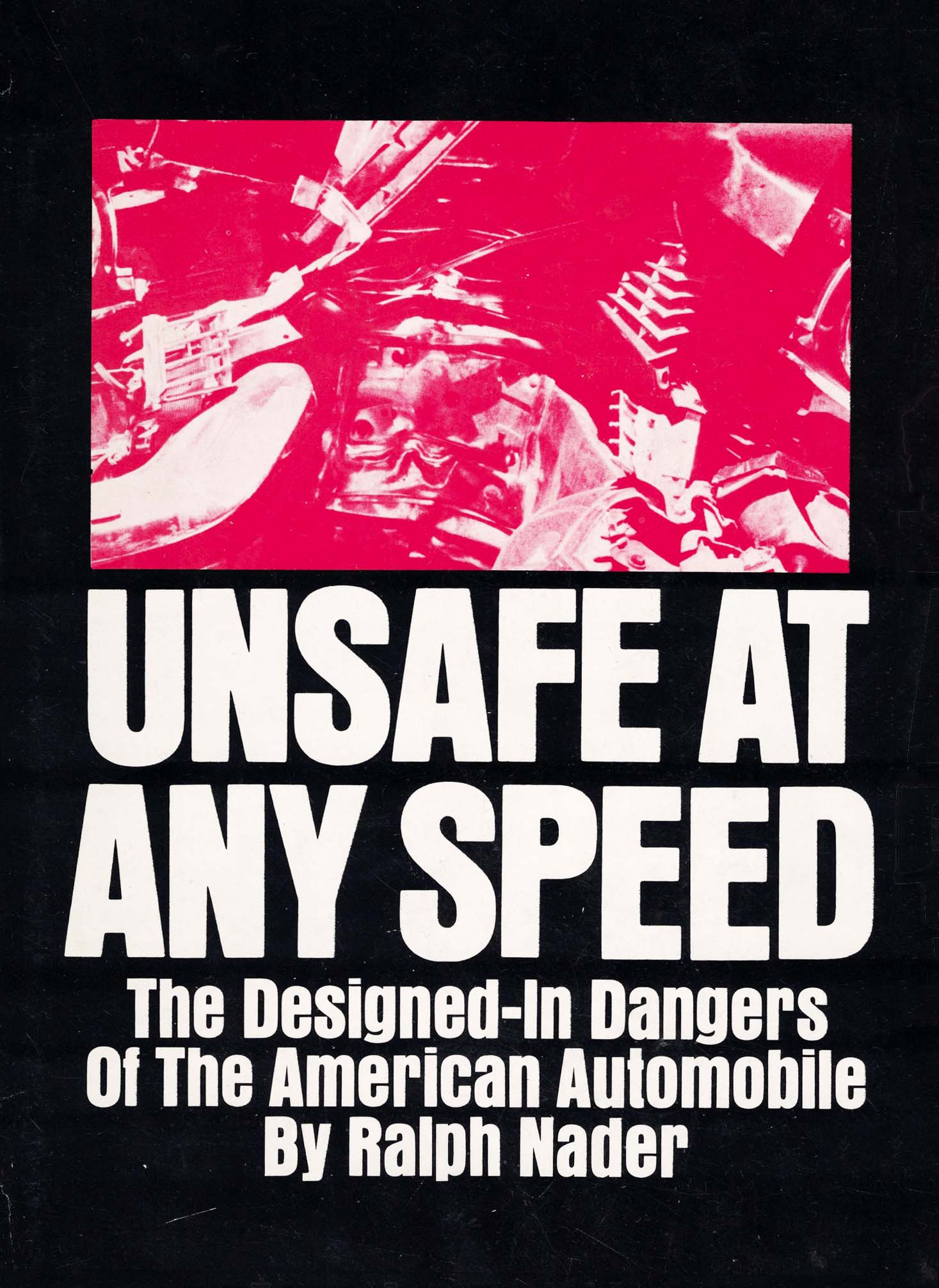

Unsafe at Any Speed

On March 22, 1965, the Senate Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization, Committee on Government Operations, began hearings on the Federal Role in Traffic Safety. Chairman Abraham Ribicoff, a former Democratic Governor of Connecticut (1955-1961) and Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare (1961-1962), explained that the goal was to review the Federal, State, and local agencies involved in highway safety “from top to bottom.” Despite a decades-long efforts, “the awful carnage on our roads and streets continues and worsens.”

On March 25, one of the witnesses was Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan, author of “Epidemic on the Highways” in the April 1959 issue of The Reporter. The article emphasized that how to make vehicles safer was well known. In 1956, the Ford Motor Company had marketed a car including many safety features with the tag line: “Exclusive New Lifeguard Design.” When the model didn’t sell, the industry dropped “safety” from its sales pitches.

Moynihan had hired a part-time consultant in 1964 for $50 a day. The consultant, a lawyer named Ralph Nader, had published an article, “The Safe Car You Can’t Buy,” in The Nation in April 1959 that tracked Moynihan’s thinking. Nader’s point was that, “It is clear Detroit today is designing automobiles for style, cost, performance and calculated obsolescence, but not – despite the 5,000,000 reported accidents, nearly 40,000 fatalities, 110,000 permanent disabilities and 1,500,000 injuries yearly – for safety.” (During the period covered by this article, the term “accidents” was in common use, not yet replaced in formal usage by “crashes.”)

In November 1965, Grossman Publishers released Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-in Dangers of the American Automobile. The book was a broad attack on virtually every aspect of the nationwide effort to reduce fatalities and injuries on the road. It reflected Nader’s view that the culprit in highway safety was not the "nut behind the wheel," as safety advocates often described drivers, but the makers of vehicles that were inherently unsafe. They were unsafe on the outside where the first crash event occurred and on the inside where occupants were tossed around inside the vehicle in a second event. The key question was “how to control the power of economic interests which ignore the harmful effects of their applied science and technology.” The book highlighted safety defects in General Motors’ (GM) sporty 1960-1963 Chevrolet Corvair. He wrote that the Corvair – a “one-car accident” – had a tendency for rear-end breakaway behavior that led to uncontrollability and rollovers.

Nader was particularly critical of highway safety “establishment” groups that he wrote were financed by the automotive and insurance industries as a cheap alternative to building safer vehicles. He singled out President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1954 Conference on Highway Safety, his Committee for Traffic Safety, and the National Safety Council (NSC) as sponsored by the automobile industry to focus on drivers. Most members of the President’s committee, Nader wrote, “know nothing whatever about traffic safety.” Meanwhile, NSC was saturating the country “with slogans, printed material, and broadcasted exhortations for safer driving.” The insurance industry, he said, had known about unsafe vehicle design for years and had even received compensation from automobile manufacturers for claims on a confidential basis.

On The Hill

Chairman Ribicoff summoned Nader on February 10, 1966. As in his book, Nader attacked presidential initiatives, safety advocates, the auto industry and its associated groups, and the Federal and State role. “A civilized society should want to protect even the nut behind the wheel from paying the ultimate penalty for a moment’s carelessness, not to mention protecting the innocent people who get in his way.”

It was a scathing indictment, but Nader singled out one Federal agency for praise:

It is encouraging to note that, at long last, the thinking and research done by a tiny group of bright, dedicated civil servants in the Bureau of Public Roads’ Office of Research and Development is beginning to find verbal receptiveness among the Department of Commerce’s top policymakers.

The Bureau of Public Roads (BPR), then part of the Commerce Department, found, in Nader’s words, “that the great bulk of accidents involve average, normally responsible drivers” performing “near the limits of their ability – considering the complexity of the traffic situation and of the driving task.” The answer, Nader emphasized, was “remedial engineering rather than reprimand.”

In response to a question from Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York, Nader said:

My point, my principal point, is . . . [that] even if people have accidents, even if they make mistakes, even if they are looking out the window, or they are drunk, we should have a second line of defense for these people and for the innocent people that are coming down the road that will be struck by them. It is the second line of defense, via the crash-worthy automobile, that should be our first priority because it is the one that is the most under our control and the one that is most enduring.

Building crashworthy automobiles was a “more enduring” way to save lives than to rely on “the impossible goal of having drivers behave perfectly at all times under all conditions in the operation of a basically unsafe vehicle and often treacherous highway conditions.”

An Investigation Backfires

Privately, Nader thought he was being followed, although he was hesitant to tell anyone. He experienced unusual circumstances, such as harassing and hang-up phone calls and young women approaching him in ways that made him think they were trying to get him into compromising situations. Friends and relatives were being interviewed by private investigators about why he wasn’t married and whether the fact that his parents had been born in Lebanon suggested he might be anti-Semitic.

The day after the hearing, the committee’s staff director and chief counsel, Jerome Sonosky, invited Nader back for a routine editorial review of the transcript of his testimony. At the Capitol, Nader stopped in the press room for a television interview. A few minutes later, two men asked a guard where Nader had gone. The guard, suspicious of the odd request, alerted a police lieutenant, who asked the men to leave.

When Sonosky heard about the incident, he informed Chairman Ribicoff. “Senator, I think a strong auto safety bill has been passed.” When the Senator asked what he meant, Sonosky replied, “They’ve followed Ralph Nader into the New Senate Office building!” News of the incident, he believed, “would give us help in strengthening” the safety bill.

Soon, articles appeared revealing that Nader’s suspicions were justified. Shortly before release of Unsafe at Any Speed, General Motors (GM) had hired an attorney who selected a private investigation firm, Vincent Gillen Associates, to find evidence that could be used to discredit Nader and undercut his attacks on GM and the Corvair. GM issued a press release on March 9 acknowledging that GM had initiated a “routine investigation through a reputable law firm to determine whether Ralph Nader was acting on behalf of litigants or their attorneys in Corvair design cases.” The investigation “did not include any of the alleged harassment or intimidation recently reported in the press.”

Chairman Ribicoff asked Nader to testify again on March 22. The publicity surrounding the investigation led to a national television broadcast of the hearing.

Nader, the scheduled first witness, was not present, so GM’s Roche was called. He was “just as shocked and outraged” by the “kind of harassment to which Mr. Nader was apparently subjected.” GM had a right “to ascertain necessary facts preparatory to litigation.” He knew nothing about it before the articles came out, but denied some of the allegations, such as using young women as sex lures for blackmail. GM, Roche said, had no interest in Nader’s political or religious views, his credit rating “or his personal habits regarding sex, alcohol, or any other subject.”

Roche was particularly concerned that people might conclude that GM was not interested in traffic safety. GM was expanding its research, engineering, and testing to improve safety, and “giving safety a priority second to none. And we consider this to be our duty.”

Nader, who had been delayed by an inability to find a taxi, finally arrived. He said it was hard to convey “what my family has had to endure, as anyone subjected to such an exposure can appreciate.” He knew that any commentator must expect criticism, but having private detectives question his family and the people he worked with “in an attempt to obtain lurid details and grist for the invidious use and metastasis of slurs and slanders goes well beyond affront and becomes generalizable as an encroachment upon a more public interest.” He could not accept that any individual had “to have an ascetic existence and steely determination in order to speak truthfully, candidly and critically of American industry, and the auto industry.”

Gillen, in a contentious appearance, also denied any wrongdoing or search for seamy behavior. He had conducted, he said, the type of investigation that would be normal to gather background on a prospective employee. Naturally, he said, he had asked about Nader’s interest in women.

Roche followed to enter a statement in defense of the Corvair, and to say he hoped Nader would accept his apologies on behalf of GM and himself “in the spirit in which I offer them.”

Instead, Nader filed suit against GM on November 14, 1966. Gillen was a codefendant, but when he told reporters Nader’s claims were delusional and suggested he see a psychiatrist, Nader sued him individually, a suit later withdrawn. Discovery found that Gillen had secretly recorded his conversation with the attorney GM had hired for the investigation. The attorney told Gillen that GM wanted to know “what makes him tick, such as his real interest in safety, his supporters, if any, his politics, his marital status, his friends, his women, boys, etc., drinking, dope, jobs – in fact, all facets of his life.” Why was Nader, then in his early 30s, unmarried. Did he have girlfriends? If not, “maybe boys, who?” They discussed whether his heritage suggested anti-semitism. “They want to get something, somewhere, on this guy to get him out of their hair, and to shut him up.”

As Time magazine headlined its article about the investigation, THE SPIES WHO WERE CAUGHT COLD.

To resolve Nader’s claims, GM settled out of court in August 1970 for $425,000 while not admitting any wrongdoing. Nader pledged that after paying expenses, he would use the balance to monitor GM’s activities. As he put it, GM was “financing their own ombudsman.”

Moving Out of the Stone Age of Ignorance

Unsafe at Any Speed had been a steady, if not spectacular seller. Nader’s testimony, the revelations about GM’s investigation, and his second appearance before the committee in a hearing covered live on television made the book exactly what GM didn’t want: a huge bestseller that helped renew the focus on the auto industry. As historian and journalist Rick Perlstein recently wrote, the 6-hour hearing on live TV launched “a legislative juggernaut.”

On March 2, 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson had submitted proposals on motor vehicle safety standards and highway safety standards. America’s highway system, he said, “is not good enough when it builds superhighways for supercharged automobiles and yet cannot find a way to prevent 50,000 highway deaths this year.” Unless something was done, 100,000 lives would be lost in 1975. The industry had not prioritized safety, but “we know that expensive freeways, powerful engines, and smooth exteriors will not stop the massacre on our roads.” The Federal Government must change these attitudes. “The people of America deserve an aggressive highway safety program.”

On June 7, the Senate Public Works Committee unanimously approved the highway safety act (S. 3052) authorizing funds for the States to use on the roads. The Senate Commerce Committee approved the motor vehicle safety act (S. 3005), also unanimously, on June 21. Both bills strengthened the President’s proposals. On June 24, 1966, the Senate spent only 6 hours on the two bills before passing S. 3005 by a roll call vote of 76 to 0 and S. 3052 on a voice vote without dissent. President Johnson called the bills landmark legislation that would “move us out of the Stone Age of ignorance and inaction.”

In the House of Representatives, the Committee on Interstate Commerce had jurisdiction over the motor vehicle bill while the Committee on Public Works had jurisdiction over the highway safety bill. The House bills were viewed as stronger than their Senate counterparts. During floor debate on the motor vehicle law, Chairman Harley O. Staggers (D-WV) of the Commerce Committee said, “the slaughter on the highways will not be materially reduced without the active and formal participation of the federal government” in regulating the motor vehicle. The motor vehicle bill passed the House on August 17, by a vote of 317 to 0. On August 18, the House approved the highway safety bill, 317 to 3.

A Conference Committee resolved differences between the Senate and House bills, with the stronger House version generally prevailing. On August 31, the Senate approved the motor vehicle safety bill on a voice vote, but postponed action on the highway safety measure due to a technicality; it was passed without a recorded vote on September 1. The House approved the motor vehicle measure, 365-0, and the highway safety measure 360-3.

The bills created a National Traffic Safety Agency (NTSA) and a National Highway Safety Agency within the Department of Commerce to administer the two programs.

The headline in the September 5, 1966, edition of Automotive News reflected the industry’s view of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966: TOUGH SAFETY LAW STRIPS AUTO INDUSTRY OF FREEDOM. The law “was much stronger than anyone could have imagined 15 months ago when the factories first tangled with Senator Abraham Ribicoff.” In the end, though, John Bugas, the Vice President of Ford Motor Company who had represented the Automobile Manufacturers Association at the hearings, called the bill “constructive legislation.”

The Signing Ceremony

On September 9, 1966, President Johnson signed the two safety bills during a ceremony in the Rose Garden at the White House. About 200 people were in attendance, including Members of Congress and representatives of safety organizations and the auto industry. As The Washington Post added, “Sitting inconspicuously near the back was Ralph Nader,” described as the “gadfly who is generally credited with arousing public demand for safer automobile design.”

President Johnson told them that nearly three times as many Americans had died in traffic accidents in the 20th century as died “in all our wars.” Auto accidents were “the biggest cause of death and injury among Americans under 35. And if our accident rate continues, one out of every two Americans can look forward to being injured by a car during his lifetime – one out of every two!”

With the Motor Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, citizens could be assured that “every new car they buy is as safe as modern knowledge knows how to build it.” The auto industry – “one of our Nation’s most dynamic and inventive industries” – would use its “skill and imagination . . . to build in more safety – without building on more costs.” The Highway Safety Act would “set up a national framework for state safety programs.” The two new laws were focused on the “highway disease.” The country had “plenty of information” on how to get “men into space and how to bring them home. Yet we don’t know for certain whether more auto accidents are caused by faulty brakes, or by soft shoulders, or by drunk drivers or by deer crossing the highway.”

He announced that Dr. William J. Haddon, Jr., would be director of NTSA and the highway safety agency. Dr. Haddon, a physician experienced in public health, was a traffic safety expert and consultant in the Commerce Department, and “one of the Nation’s leading traffic safety experts.”

President Johnson concluded by saying he was proud to sign the two bills that would help “cure the highway disease: to end the years of horror and to give us, instead, years of hope.”

After the signing, President Johnson greeted the guests, handing out the pens he had used during the ceremony. The New York Times reported that Nader was one of the last guests to receive a handshake. “The President shook Mr. Nader’s hand briefly without any sign of recognition.” The President had long since run out of pens used to sign the two bills, but a White House aide gave Nader a White House ceremonial pen.

Nader had handed reporters a statement that said, “For the first time, the potential exists for finding the remedies to reduce the tens of thousands of deaths and millions of injuries arising from automobile collisions every year.” He urged the auto industry to “compete dynamically to give the people the maximum safety standards, without unjustifiably raising prices.” He particularly praised NTSA, which would provide leadership to enforce the new laws. “Above all, the new agency will require the support and the understanding of government, industry and the public. For all three should be the ultimate benefactors of this historic legislation.”

A few days later, Washington Post reporter Norman Mintz wrote that, “The auto safety bill, a legislative vehicle with Ralph Nader under the hood, rolled up to the White House a few days ago after an eventful trip from Nowheresville.”

The Aftermath

A few weeks after signing the two safety bills, President Johnson signed the Department of Transportation Act of 1966, creating the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). When DOT opened on April 1, 1967, the new Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) incorporated BPR from the Commerce Department to administer the Federal-aid highway program, the two motor vehicle and highway safety bureaus, and the Bureau of Motor Carrier Safety, formerly in the Interstate Commerce Commission. The motor vehicle and highway safety bureaus under Dr. Haddon would soon be referred to simply as the National Highway Safety Bureau.

Dr. Haddon served as Director until February 14, 1969, when he resigned to become president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Douglas W. Toms served as acting director.

Secretary of Transportation John A. Volpe (1969-1972) used his administrative authority on March 22, 1970, to remove the motor vehicle bureau from FHWA to become a new DOT organization reporting to him. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1970, signed by President Richard M. Nixon on December 31, 1970, provided the statutory language in Title II (“Highway Safety Act of 1970”) to change the bureau’s name to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, with Toms as its first Administrator (1970-1973). FHWA remained responsible for administration of the highway safety legislation.

In a 1989 oral history for the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, former Federal Highway Administrator Francis C. “Frank” Turner (1969-1972) recalled that when he was appointed to the position after a lifetime career in BPR/FHWA, “one of the first things that I did was to startle the Secretary by proposing that I wanted to transfer [NTSA] out of FHWA and create it, set it up as a completely separate and equal administration.” He explained that, “They operated on a different frame of mind from what the highway program did, for one thing. They had different individuals and a different philosophy for everything.” Further, he didn’t think NTSA’s employees liked being part of FHWA. “They felt like they had been lowered and one thing and another, and I knew that, and I thought that that was poor morale . . . to promote safety.” The new agency should have its own Administrator. “Instead of him reporting to me, why, he would go his merry way parallel to me.” Turner recalled Secretary Volpe’s response, “Well,” Volpe said according to Turner, “you have really come up with a good idea. A different idea, haven’t you?” Turner replied, “Yeah.”

On September 14, 1966, Under Secretary of Commerce for Transportation Alan S. Boyd, who would become the first Secretary of Transportation on January 16, 1967, said during a news conference that he did not expect “any dramatic changes” from the new motor vehicle safety program, adding, “Because of the long-range nature of the problem, we don’t expect any miracles . . . . This is a long pull that we’re in for.” His prediction proved accurate.

According to FHWA’s annual Highway Statistics, fatalities continued to increase after 1966, reaching an all-time high of 55,600 fatalities in 1973 (a fatality rate of 4.1 per 100 million vehicle miles traveled). From that peak, the number of fatalities began a gradual decline, with occasional ups and downs, to 36,096 in 2019 (fatality rate: 1.10). A 2015 NHTSA report estimated that 613,501 lives had been saved from 1960 to 2012 because of government-mandated changes, mainly in automobile design. “Thanks to advanced engineering, in-depth research and analysis of crash data, newer vehicles are built better and have more safety features to protect you.”

As the fatality numbers reflect, change did not occur quickly. But on a moment in time on September 9, 1966, the fight against highway crashes took a major turn that continues today to make motor vehicles as well as highways safer.