Zero Milestone - Washington, DC

by Richard F. Weingroff

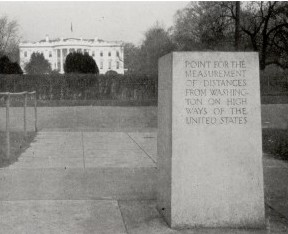

If you've ever visited Washington, DC, perhaps you went to the Ellipse, where you can get a great view of the South Lawn of the White House. At the best spot for taking a photo, you may have noticed a hip-high monument that claims to be the point for measuring distances from Washington. Perhaps you noticed the statement on one side about the Lincoln Highway or the statement on the other about the Bankhead Highway. And perhaps you wondered, "What is this thing?" Here is its story.

The Zero Milestone was conceived by good roads advocate Dr. S. M. Johnson in 1919. He explained it in a proposal submitted on June 7, 1919, to Colonel J. M. Ritchie of the U.S. Army's Motor Transportation Corps:

It seems to me the time has come when the Government should designate a point at which the road system of the United States takes its beginning, and that the spot should be marked by an initial milestone, from which all road distances in the United States and throughout the Western hemisphere should be reckoned.

Rome marked the beginning of her system of highways which bound her widely scattered people together by a golden milestone in the Forum. The system of highways radiating from Washington to all the boundaries of the national domain and all parts of the Western hemisphere will do vastly more for national unity and for human unity than even the roads of the Roman Empire . . . .

This stone will endure as the generations and the centuries come and go, till time shall be no more. If that golden milestone in Rome still has the power to fire the imagination of men, how much greater will be the appeal of the Washington milestone as time goes on and American history grows ever richer in deeds of service to humanity.

The spot should be marked and, he added, serve as the starting point for the motor convoy the U.S. Army was preparing to send across the country.

Colonel Ritchie submitted the letter to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, who approved the idea. Now it was up to Dr. Johnson to provide the Zero Milestone. Dr. Johnson learned that an Act of Congress would be needed before a monument could be erected in the District of Columbia. With time short before the motor convoy left Washington on July 7, he secured a permit from the Officer in Charge of Public Buildings and Grounds for a temporary marker that could be replaced with a permanent marker after the necessary legislation had been secured.

A New Era Begins

On July 7, 1919, the temporary marker for the Zero Milestone was dedicated on the Ellipse south of the White House during ceremonies launching the U.S. Army's first attempt to send a convoy of military vehicles across the country to the West Coast. The temporary marker unveiled during the ceremony had been provided as a gift from Mr. F. W. Hockaday of Wichita, Kansas, president of the National Highway Marking Association.

On July 7, 1919, the temporary marker for the Zero Milestone was dedicated on the Ellipse south of the White House during ceremonies launching the U.S. Army's first attempt to send a convoy of military vehicles across the country to the West Coast. The temporary marker unveiled during the ceremony had been provided as a gift from Mr. F. W. Hockaday of Wichita, Kansas, president of the National Highway Marking Association.

Secretary Baker accepted the temporary marker on behalf of the government. Then he launched the convoy-initially called a "motor truck train" in news accounts. He told the assembled dignitaries and prominent local citizens:

This is the beginning of a new era. The world war was a war of motor transport. It was a war of movement, especially in the later stages, when the practically stationary position of the armies was changed to meet the new conditions. There seemed to be a never ending stream of transports moving along the white roads of France.

One of the remarkable and entirely new developments of the war was the inauguration of a regular timetable and schedule for these trucks. In the daytime they were held in thickly wooded sections, but at night each one started out with a map and regular schedule which was as closely followed as the modern railroad. In no previous war had motor transportation developed to such an extent.

Then, he directed the leader of the convoy, Lt. Colonel Charles McClure to "proceed by way of the Lincoln Highway to San Francisco without delay . . . ." They were to drive to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where they would turn left on the Lincoln Highway, the most famous highway of its day, and head to San Francisco. Representative Julius Kahn of California presented two wreaths to Colonel McClure to be given to California Governor William D. Stephens.

As it turned out, they faced nothing but delay. After all, they would be taking what The Evening Star newspaper of Washington called the "longest and most thoroughly equipped and manned Army motor train ever assembled" on a highway that, just a few years earlier, had been described as "an imaginary line, like the equator!"

The Evening Star described the start of the journey:

This long Army motor train, composed of over sixty trucks and with a personnel of more than 200 men, rumbled slowly out of the city on a journey across the continent shortly after 11 o'clock this morning. It is to be self-maintained and self-operated and carries road and bridge building equipment, so that in case of a wash-out repairs can be speedily made.

The Tank Corps Observer

The convoy is best known today because a young officer, brevet Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower (soon to return to his peacetime rank of Captain), participated in it. He almost didn't go. He was thinking of leaving the Army-he didn't see much future for himself, stuck in a tank unit, never having made it to Europe during the war. He decided to go along as an observer "for a lark." He missed Secretary Baker's speech and the opening ceremonies. Instead, he joined the convoy in Frederick, Maryland. By then, the convoy had already experienced its first breakdowns--a kitchen trailer broke its coupling, a fan belt broke on one of the staff cars, and one of the trucks had to be towed into camp with a broken magneto. The 46-mile trip had taken over 7 hours.

Driving across the country, the convoy would need their road and bridge building equipment. Participants experienced every nightmare common to interstate motoring in the 1910's, plus additional troubles unique to the heavy vehicles they were taking across the country. Aside from regular mechanical problems, the convoy had to deal with vehicles stuck in mud or crashing through wooden bridges, roads as slippery as ice (25 trucks skidded into a roadside ditch west of North Platte, Nebraska), roads with the consistency of "gumbo" or built on shifting sand, and extremes of weather from desert heat to Rocky Mountain freezing.

And everywhere they went, people turned out to greet them and offer them food, lodging, and friendship. Officials estimated that more than 3,250,000 Americans greeted the convoy, which gave America an opportunity to thank the Army for winning the war and to see some of the vehicles that made the victory possible. Everywhere, too, there were speeches, speeches, and more speeches by Army officers, Governors, Mayors, local dignitaries, important citizens, and Dr. Johnson. The tireless good roads advocate who had conceived the idea of erecting the Zero Milestone had also worked with the Lincoln Highway Association to arrange the convoy. Now he accompanied it west, making good roads speeches from coast to coast.

Colonel McClure finally led the convoy into San Francisco on September 6. Two destroyers escorted the ferryboats on which the convoy crossed the bay from Oakland to San Francisco. The participants passed along gaily decorated streets and between cheering lines of people to Lincoln Park, the terminus of the Lincoln Highway. The men received special medals for their exploits, but what Eisenhower later recalled was, "On the last day, the speeches ran on and on."

The 3,200-mile trip, Eisenhower said later, "had been difficult, tiring, and fun." His formal "Report on Trans-Continental Trip," dated November 3, 1919, stated that the roads east of Illinois and in California were good, although some old wooden bridges were in poor shape. He concluded:

Extended trips by trucks through the middle western part of the United States are impracticable until roads are improved, and then only a light truck should be used on long hauls. Through the eastern part of the United States the truck can be efficiently used in the Military Service, especially in problems involving a haul of approximately a hundred miles, which could be negotiated by light trucks in one day.

All participants came away convinced of the necessity of improving the Nation's roads. The difference was that, someday, Eisenhower would be in a position to do something about it. In his memoir, he recalled the impact of the 1919 convoy on him:

A third of a century later, after seeing the autobahns of modern Germany and knowing the asset those highways were to the Germans, I decided, as President, to put an emphasis on this kind of road building. When we finally secured the necessary congressional approval, we started the 41,000 miles of super highways [now 42,800 miles] that are already proving their worth. This was one of the things that I felt deeply about, and I made a personal and absolute decision to see that the nation would benefit by it. The old convoy had started me thinking about good, two-lane highways, but Germany had made me see the wisdom of broader ribbons across the land.

President Eisenhower was never in the slightest doubt that the Interstate System was one of the most important accomplishments of his two terms in office. And he always cited the 1919 convoy as one of the reasons he clearly grasped the importance of good roads.

When Secretary Baker said, "This is the beginning of a new era," he had no idea how right he would prove to be.

The Second Convoy

The second convoy was promoted by the Bankhead Highway Association to follow its route from Washington to San Diego, California. The Bankhead Highway was established in Birmingham, Alabama, in October 1916, and named after U.S. Senator John H. Bankhead of Alabama. The Senator, a long-time booster for the cause of good roads, had been the chief sponsor of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which President Woodrow Wilson had signed on July 11. The 1916 Act created the Federal-aid highway program that is still in operation today.

After several pathfinding tours, the Bankhead Highway Association ratified its 3,450-mile route in February 1920. The association estimated that 1,000 miles had "been improved with either permanent paving or hard substance." In January 1920, Senator Bankhead had asked Dr. Johnson to visit General Charles B. Drake, Chief of the Motor Transportation Corps, to present the following letter:

I have requested Dr. S. M. Johnson to call on you and present in person our request for a Motor Convoy Expedition over the Bankhead Highway. I am cognizant of the results of last summer's Convoy, and it is my deep desire that a similar benefit may accrue to the South and Southwest through another Convoy.

I am sure that, while the regions of my particular interest would receive special benefit, the entire nation would profit through the stimulus given to the movement to which the nation should address itself-the construction of a system of national highways.

In May, the War Department approved the proposal to dispatch a convoy over the Bankhead Highway under Colonel John F. Franklin, the Expeditionary Commander. Franklin, a West Point graduate with 20 years of Army experience, had served in Pershing's supply train in 1916 during the Army's incursion into Mexico following Pancho Villa's raid into New Mexico-one of the military's first uses of motor vehicles--and later served in France. J. A. Rountree, secretary of the Bankhead Highway Association, went along as field director and spokesman.

On June 14, dignitaries gathered on the Ellipse at the site of the temporary Zero Milestone marker that had been placed at the site at the start of the first U.S. Army convoy in July 1919. Secretary of War Baker was joined for the ceremony by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, Secretary of Commerce Joshua W. Alexander, Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams, and Governor W. P. G. Harding of the Federal Reserve Board.

One person missing was Senator Bankhead. The 77-year old Senator had died on March 1, the Senate's oldest member to that time and its last survivor of the Civil War.

Secretary Baker explained the importance of good roads and motor trucks to the French victory against the Germans at Verdun. He urged the men to live up to the standard set in that war. Navy Secretary Daniels admitted he had been skeptical about the wisdom of spending so much money on good roads-his theory being that before long, everyone would be flying. However, since flying was still only indulged in by the few, the Secretary felt that for the present generation, good roads were an economic necessity. Commerce Secretary Alexander hoped the United States would soon have a chain of national highways and that every dollar used for this purpose would bring a large return. Mr. Harding, a close friend of the late Senator, called him "The Father of Good Roads in the United States."

General Drake of the Motor Transportation Corps explained why the U.S. Army had decide to dispatch the convoy:

[To] assist in the development of a system of national highways by bringing before the public in an educational way the necessity for such a system; to provide extended field service in connection with the training of officers and men in motor transportation; to recruit personnel for the various branches of the army; to secure data on road conditions throughout the territory in the immediate vicinity of the highway along which the convoy will operate; and to secure data relative to the operation and maintenance of motor vehicles.

Two wreaths were presented to Colonel Franklin for delivery to Governor Stephens of California. Secretary Baker presented the first wreath. The second came from Mrs. A. G. Lund, Senator Bankhead's daughter. An account of the ceremony in AAA's American Motorist magazine observed, "her presence at the starting ceremonies added a touch of sentiment to the occasion that was felt by all present who were acquainted with the lifetime hopes and ambitions of her distinguished father."

The plan was for Colonel Franklin to travel 40 to 65 miles a day and arrive in San Diego on September 15. The convoy, which consisted of 32 officers and 160 enlisted men traveling in 50 trucks and automobiles, was then to proceed to Los Angeles, where the equipment would be distributed as part of the government's distribution of surplus war equipment to State and local governments.

The convoy proceeded to Atlanta, Georgia, with Governors and other dignitaries greeting and accompanying them along the way. They arrived on June 30 after experiencing little trouble on the roads despite bad weather. Heavy rains, however, created major problems for the convoy as it struggled to Memphis, where it found that floods in Arkansas had inundated the roads between Memphis and Little Rock. The convoy detoured to Helena, where the vehicles were ferried across the Mississippi River. The convoy also had to ferry across the White River in Arkansas. The Bankhead Highway Association's account of the convoy observed that, "The 'black gumbo' of Mississippi proved very troublesome and the heavy trucks had difficulty in getting through."

After another detour to avoid construction of the new road between Arkadelphia and Fulton, the convoy reached Texas, which consumed 1,087 miles, practically a third of the total distance of the Bankhead Highway:

The trip, long as it was, would have been made quicker had it not been for high waters that cut off both highway and railroad travel at one point for more than a week. At Sweetwater the convoy was held up because the roads were under water, and trains were stopped because the tracks were in the same condition.

As the convoy rolled into El Paso, the participants felt "a sigh of genuine relief . . . for the worst was over." On the "excellent highway" into El Paso, one sergeant said he did not believe there was such a road left in the world. Colonel Franklin, who was fully familiar with the roads of New Mexico and Arizona, assured them that they would not encounter the mud that had "proved so troublesome." Unexpectedly, therefore, the road between Tucson and Yuma, Arizona, would prove to be "the worst encountered by the convoy." The Bankhead Highway Association's account explained:

From Ajo to the Pima county line the road was passable. But just across the Pima county line in Maricopa and before reaching Yuma county, the convoy met the worst stretch of road, having difficulty in extracting itself from the clinging sands. From Sentinel to Wellton heavy sandy road was encountered in spots which caused the convoy's speed to be materially reduced. From Wellton to Yuma the convoy made record time, experiencing no difficulty on the road.

The association's account offered the following defense of Arizona:

According to the officers in charge of the convoy, the roads in Arizona are on the whole as good as the roads found in any other state through which the convoy has passed. However, that is not saying a great deal, for the country as a whole has not as yet awakened to the fact that good roads are as essential in modern life as railroads.

The arrival of the convoy was big news in each town and city. As had happened in 1919 during the passage of the first convoy, the Bankhead Highway convoy was greeted by welcoming ceremonies and, in the last town each day, dances. And speeches, including Rountree's good roads speeches.

At last, on October 2, the convoy reached San Diego. A local delegation greeted the convoy at 2 pm and led the way into the city. The San Diego Union described the entry:

Headed by the car occupied by [local booster and good roads advocate] Colonel [Ed] Fletcher, Major Franklin and J. A. Rountree, secretary of the Bankhead Highway Commission and field director of the convoy, the procession wound slowly down into the city.

At Fourth and Walnut, the convoy was met by motorized detachments representing the navy activities here, the army stations of Fort Rosecrans and Rockwell Field, and two naval bands . . . . The convoy went into camp in the park, north of the exposition buildings, and as the men turned out for "Assembly," Colonel Fletcher, introduced by the commanding officer, made what one dusty truck driver termed "the best speech of the whole trip."

Colonel Fletcher's speech was not oratory, nor intended as such. Simply and directly, he told the officers and men of San Diego's welcoming spirit and invited them to take part in the celebration planned in their honor. Applause such as only a crowd of army men can give greeted him as he told the men of the chicken dinner to which the American Legion last night invited them, of today's "launch ride" about the bay in a navy destroyer, of the free bathing privileges of the Service plunge and the auto ride about the city, planned for the enlisted men.

While the enlisted men were enjoying their "feed" in the Cristobal Cafe in Balboa Park and a dance sponsored by the women's auxiliary of the San Diego post of the American Legion, the officers were entertained at a banquet in the U.S. Grant Hotel. After a series of speeches, Colonel Fletcher presented a silver loving cup to Rountree. On one side it was inscribed:

Presented to J. A. Rountree, secretary Bankhead National Highway Association, on behalf of its members and admiring friends in recognition of his splendid service in conducting the Bankhead Highway Transcontinental Convoy, Washington, D.C., June 14th, San Diego, October 6, 1920.

On the other side, a map of the Bankhead Highway had been engraved.

Rountree then carefully unwrapped a wreath given to him in Washington by Senator Bankhead's widow, Mrs. Tallulah J. Bankhead,[1] for delivery to "the city of the Silver Gate." Mayor L. J. Wilde accepted the wreath.

Colonel Franklin was then introduced. The San Diego Union account explains that his address was delayed by lengthy applause:

"After 111 days on the road," began [Colonel] Franklin, "you will believe me when I tell you it is a pleasure to be here." Then, in an address replete with interesting incidents well told, he related some of the obstacles met and overcome in the long run. His story of the big trailer "hanged on" the convoy by the ordinance department, and of how it was finally "ditched"-off the Talapoosa bridge and the narrow escape of a truck which crashed through its flimsy floor-of the "Admiral of El Paso," who did convoy duty across the Rio Grande-of the "gumbo" and bad bridges of Mississippi, and the hot stretches of sand and waste in the western states, was voted a classic in impromptu narrative.

According to the association's account, "Washington sent the convoy off with an impressive ceremony, and San Diego received it in like manner."

The main purpose of the convoy had been achieved with the arrival in San Diego, but a few more details remained to be accomplished. The convoy left San Diego on October 4 and arrived in Los Angeles the following day. During 3 days in the city, Colonel Franklin presented the two ceremonial wreaths, given to him in Washington, to Governor Stephens. By then, the U.S. Army had ordered the convoy to continue to San Francisco, which was reached on October 13. At the Presidio, the Bankhead Highway convoy was over.

As far as Rountree was concerned, it had been a total success. He estimated that the convoy traversed more than 4,500 miles. He had delivered over 250 addresses on good roads to more than 500,000 people. With Congress considering legislation, known as the Townsend bill after Senator Charles E. Townsend of Michigan, that would create a National Highway Commission to build a national system of highways, Rountree was convinced the Lincoln Highway and the Bankhead Highway would be taken over by the Federal Government and rebuilt to high standards. The two convoys had proven their national importance.

Things did not work out that way. The Townsend bill was defeated. Instead, Congress passed the Federal Highway Act of 1921, which corrected defects in the original Federal-aid highway program. The Federal Government would not build national highways. Instead, with help from the State highway agencies, the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads would designate roads that would be eligible for improvement with Federal-aid highway funds. The Federal-aid system would include up to 7 percent of the Nation's total road mileage, with three-sevenths of the system being "interstate in character." Federal-aid funds would be made available to the State highway agencies to help improve the roads.

Securing the Permanent Milestone

Even before the second convoy had left for its cross-country trip on the Bankhead Highway, Dr. Johnson had secured approval for the permanent Zero Milestone. He had drafted a bill authorizing the permanent marker. With the endorsement of Secretary Baker, the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, the American Automobile Association (AAA), the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, and other organizations, Congressman Kahn introduced the bill on January 5, 1920.

H. J. Res. 270, which was approved on June 5, 1920, authorized the Secretary of War to erect a Zero Milestone, the design to be approved by the Commission of Fine Arts and installed at no expense to the government. At the Secretary's request, Dr. Johnson took charge of the details. He hired Horace W. Peaslee, a Washington architect, to design the Zero Milestone and supervise its construction. Dr. Johnson also raised funds. The principal contributors, according to Dr. Johnson, were:

[The] children of the late Senator Bankhead, also F. W. Hockaday, of Wichita, Kansas; F. A. Sieberling, of Akron, Ohio; Charles Springer, of Santa Fe, New Mexico; Charles Davis, of Cape Cod, Massachusetts; Durant Motors Company; F. G. Chandler, of Cleveland, Ohio; R. D. Chapin, of Detroit, Michigan; Packard Motor Company; General Motors Corporation; W. O. Rutherford, of Akron, Ohio; Henry B. Joy, of Detroit, Michigan; Col. Benehan Cameron, of Staggville, North Carolina; American Automobile Association; National Highways Association; the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce; and Lee Highway Association.

This was a who's who list of good roads advocates. For example, Sieberling, closely associated with the Lincoln Highway, headed Goodyear Tires. Joy, president of Packard, was also long associated with the Lincoln Highway. Chapin, an auto executive, was president of the Chamber, while Davis was president of the National Highways Association. Cameron was president of the Bankhead Highway Association.

Peaslee decided to engrave the purpose of the Zero Milestone on the side facing south toward the Washington Monument:

POINT FOR THE MEASUREMENT OF DISTANCES FROM

WASHINGTON ON HIGHWAYS OF THE UNITED STATES

The west face notes the 1919 tour:

STARTING POINT OF FIRST TRANSCONTINENTAL MOTOR CONVOY OVER THE LINCOLN HIGHWAY, JULY 7, 1919

The engraving on the east face commemorates the second Army convoy:

STARTING POINT OF SECOND TRANSCONTINENTAL MOTOR CONVOY OVER THE BANKHEAD HIGHWAY, JUNE 14, 1920

According to information Dr. Johnson provided at the time, the bronze disc on top of the milestone is "an adaptation from ancient Portolan charts of the so-called 'wind roses' or 'compass roses' from the points of which extended radial lines to all parts of the then known world-the prototype of the modern mariner's compass."

The Zero Milestone is located at the Meridian of the District of Columbia, 77.02', which previously was marked by the "Jefferson Stone" placed in 1804. The latitude is 38.53' 43.32". The elevation is 23'65" above sea level. A brass plate placed on the ground at the north base of the milestone-now illegible from wear and tear-originally read:

THE U.S. COAST AND GEODETIC SURVEY DETERMINED THE LATITUDE LONGITUDE AND ELEVATION OF THE ZERO MILESTONE.

Dedicating the Milestone

The permanent Zero Milestone was dedicated in a ceremony on June 4, 1923. The ceremony coincided with the opening of the Washington Convention of the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. As a result, according to Dr. Johnson, the occasion brought together "more automobiles than were ever before assembled in the city." About 8,000 people attended the ceremony.

Early on, the U.S. Army Band performed "Hail! Hail! The Caravan!" The march had been written for the occasion by Virginia Monro (words) and Wilmuth Gary (music). "The magic links of byways, the golden chains of highways," the lyric proclaims, "radiate from our DC enduring ties of liberty."

With President Warren Harding in attendance, the ceremony continued with brief addresses by Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace, Chief Thomas H. MacDonald of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, and auto industry representatives. Then, Dr. Johnson presented the Zero Milestone to the Nation. After explaining the origins of the milestone, he concluded:

We have taken our stand for a paved United States. This monument is placed here to mark the beginning of a system, but a beginning implies continuance and completion. The use of the automobile is universal, therefore pavement must be universal. Until this is accomplished, we will not be living in the spirit of the age in which our lives are cast.

Mr. President, on behalf of Lee Highway Association, and through the cooperation of a number of public-spirited citizens, including the children of the late Senator John H. Bankhead, father of the Federal Highway Act, and of national organizations, including the American Automobile Association, the National Automobile Chamber of the Commerce, and the National Highways Association, I have the honor to present this monument, to be the beginning of our system of national highways, a standard of linear measurement on the highways radiating from this place and as a symbol of the spirit of this, the motor age of progress.

President Harding accepted the milestone on behalf of the Federal Government. He began with references to the original Golden Milestone in Rome:

My countrymen, in the old Roman forum there was erected in the days of Rome's greatness a golden milestone. From it was measured and marked the system of highways which gridironed the Roman world and bound the uttermost provinces to the heart and center of the empire. We are dedicating here another golden milestone, to which we and those after us will relate the wide-ranging units of the highway system of this country.

He explained that placing the Zero Milestone in Washington was appropriate. Referring to the two decades of highway development since the beginning of the motor age, he said:

[Our] advance in this respect has been phenomenal, making it most fitting that a recognized center of the highway system should at this time be set up.

It is appropriate, too, that our golden milestone has been here placed in the National Capital, the spiritual and institutional center of the nation. From it will diverge, to it will converge, the ceaseless tides whose movement will always keep our wide-flung population in that close intimacy of thought and interest and aim which is so necessary to the maintenance of unity and nationality.

There was, he added, another reason for its location:

It marks the approximate meeting place of the Lincoln Highway and the Lee Highway; of the northern and southern systems of national roads. From it we may view the memorial to Lincoln and the home of Lee [the Custis-Lee Mansion, which in that time was visible just beyond the Lincoln Memorial on a hill at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia]. It marks the meeting point of those sections which once grappled in conflict, but now are happily united for all time in the bonds of national fraternity, of a single patriotism, and of a common destiny.

In closing, he said:

We may fittingly dedicate the zero milestone to its purpose in the hope and trust that it will remain here through the generations and centuries, while the republic endures as the greatest institutional blessing that Providence has given to any people.

Other Zero Milestones

Advocates attempted to spread the Zero Milestone idea to other cities. The value of many milestones "will be at once recognized," as AAA explained in the October 1923 issue of its magazine American Motorist:

Motorists are familiar with the conflicting statements of roadside markers as to the distance to or from a certain city or town, all because the mileage was measured from different points . . . . With official milestones in each city and town, all disputes as to distances between certain cities or towns can be accurately settled as the understanding will be that the distances between milestones will be taken.

Several milestones were placed around the country. On November 17, 1923, for example, the Lee Highway Association placed the Pacific Milestone in Grant Park opposite the U.S. Grant Hotel at the western terminus of the Lee Highway in San Diego, California. President Harding had expected to participate while on an extended western tour. However, he died in San Francisco on August 2, 1923. Nevertheless, presidential participation was arranged for the ceremony. President Calvin Coolidge pressed a key in the White House to release an electric impulse that started the ceremony, which was attended by 20,000 people. Colonel Fletcher read President Coolidge's remarks, which concluded:

The monument may well be dedicated to the purpose of marking the meeting place of the splendid highway with the waters of the Pacific, in the hope that it may hasten the coming day of a perfected system of highway communication throughout the entire nation.

The marble milestone included a bronze tablet:

THE CITIZENS OF SAN DIEGO IN DEDICATING THE PACIFIC MILESTONE, NOVEMBER 17, 1923, HEREBY GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGE THE UNTIRING EFFORTS OF COL. ED FLETCHER IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF A SOUTHERN TRANSCONTINENTAL HIGHWAY

A similar milestone was dedicated in Nashville on May 12, 1924, in the southeast corner of Memorial Park at Union Street and Sixth Avenue. The canvas cover was pulled from the Zero Milestone at 2 pm by two "little misses," as they were described in Tennessee Highways and Public Works. The children were Sarah Peay, daughter of Governor Austin Peay, and Elizabeth Cornelius, whose father Charles was president of the Nashville Automobile Club. The Governor declared that the marker will remain through the years as the "headstone of the State Highway System."

A Gathering of Visionaries

Given the link to President Eisenhower and the 1919 convoy, the Zero Milestone on the Ellipse was the site of a gala honoring the "Visionaries of the Interstate" on June 26, 1996. The gala commemorated the 40thanniversary of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which President Eisenhower signed to launch the Interstate System (actually signed June 29, 1956). During the ceremony, Vice President Al Gore honored four of the Founding Fathers of the Interstate System: President Eisenhower (accepted by his granddaughter, Susan Eisenhower), Congressman Hale Boggs (his wife, former Congresswoman Lindy Boggs, accepted the award), former Federal Highway Administrator Frank Turner (present for this honor), and the Vice President's father, Senator Al Gore, Sr. (one of the chief authors of the bill, also present).

Vice President Gore said:

Tonight we meet to celebrate the 40thanniversary of the Interstate Highway System and the four great Americans who made it possible . . . . And as we celebrate this anniversary, I really can't think of a better place to gather than on the Ellipse, at the Zero Milestone Marker. The Zero Milestone, of course, is the marker from which all distances from the nation's capital are supposed to be measured. In many ways the Interstate Highway System is a marker itself from which all legislation should be measured. Our nation's greatest accomplishments, whether the Interstate Highway System or the Marshall Plan or many others, are often those that receive bipartisan support.

And so it stands. The Zero Milestone in Washington never became the American equivalent of Rome's Golden Milestone. Today, it remains in place, baffling tourists and serving mainly as a resting place for their belongings while they take photographs of each other standing in front of the White House. It is forgotten for the most part. Periodically, it is threatened with removal by the National Park Service as it considers options for revitalizing the Ellipse. But for historians, the Zero Milestone marks the place where "a new era" began.

[1] The actress Tullulah Bankhead was the granddaughter of Senator and Mrs. Bankhead.