A Moment in Time: President Harding's Landmark Act

by Richard Weingroff / FHWA News 2024-2025

This column often highlights a moment in time when a well-regarded President, such as Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, or Dwight D. Eisenhower, do something unique about highways. But, to be fair, even our worst Presidents occasionally did something good about highways.

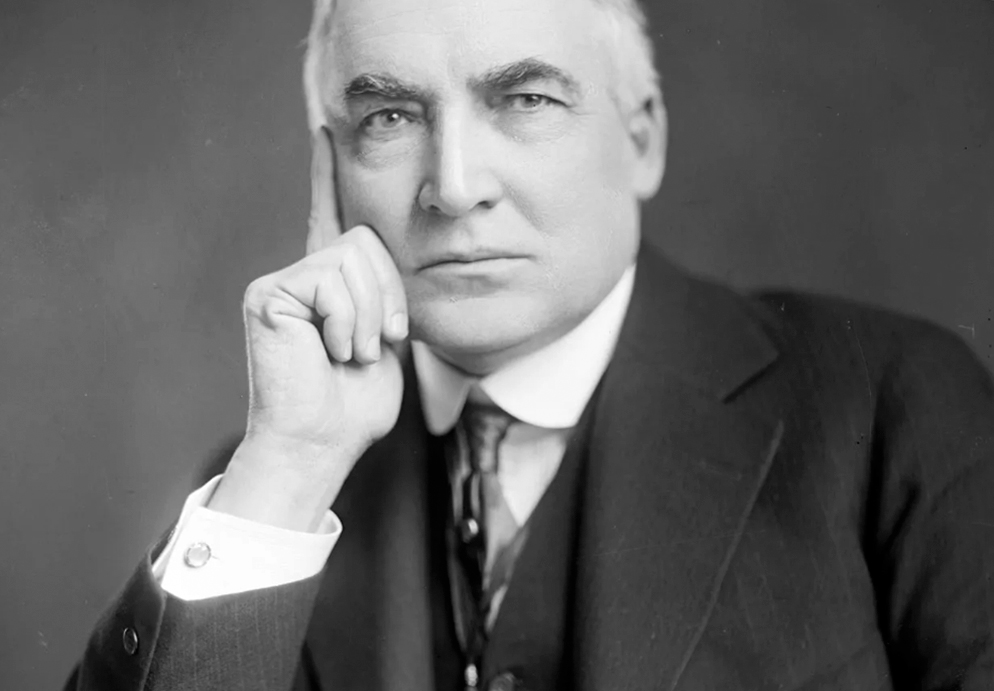

That brings us to President Warren G. Harding, a newspaper editor, former State official, and U.S. Senator from Ohio. His Presidency lasted from March 4, 1921, until his death in San Francisco on August 2, 1923, following a transcontinental trip he called a Voyage of Understanding that took him across the country and to Canada and the territory of Alaska – the first sitting President to visit them. In a recent survey of presidential historians, Harding came in 40th among the ranked 45 Presidents, just above slave-owning William Henry Harrison, No. 41, who served only a month in 1841 before dying in office and leaving the country with slave-owning former Vice President John Tyler of Virginia (1841 to 1845), who was unpopular among his contemporaries, was kicked out of his Whig party, and adopted the Confederate cause during the Civil War until he died in 1862, just before taking office in the Confederate House of Representatives – and he's No. 37!

After campaigning in 1920 for a "return to normalcy," President Harding – many questioned his ability to do the job, but everyone agreed he looked the part – would preside over one of the most corrupt Administrations in American history. The best known problem was the Teapot Dome Scandal that emerged in 1922. Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyoming, and other locations, to private oil companies at low rates without competitive bidding. Investigation of the numerous scandals undermined Harding's reputation, although he never directly benefited from them.

And yet, at a moment in time on November 9, 1921, No. 40 signed the Federal Highway Act of 1921, the landmark bill that set the Federal-aid highway program on a system-based path to success. In fact, if Presidents were judged solely on their accomplishments on roads, President Harding would be near the top with Presidents Franklin Roosevelt (No. 2), Truman (No. 6), Eisenhower (No. 8), and Woodrow Wilson (No. 15). Believe it or not! Okay, maybe not.

The Lover of Roads

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

For Warren Harding, automobile travel was a favorite pastime, along with golf, whiskey, and poker. A contemporary account in The Baltimore Sun described his driving. "He could qualify as an expert chauffeur, and some of his passengers say that he 'steps on it' a trifle too hard to suit them, which means that he likes to 'hit it up.'" (In other words, he was a speeder.) He was the first President who had driven automobiles as opposed to being driven in them. And after being elected to the Senate in 1914, he often drove his Locomobile between his home in Marion, Ohio, and Washington on the National Old Trails Road – a named trail dating to 1912 from Baltimore and Washington to Los Angeles.

Photo courtesy of White House History / Library of Congress

He brought his Locomobile to the White House and purchased a new one in 1921 that cost $9,000 (the equivalent of $142,304 today). However, the official White House automobile was a Pierce-Arrow limousine with AAA's silver emblem on the front, positioned above the Presidential Coat of Arms. The Secret Service would not let him drive any of the vehicles.

He also was the first President to ride to his inauguration in an automobile. The vehicle was a Packard Twin 6 supplied by the Republican National Committee. The Washington Post wrote, "President-elect Harding's action in choosing a more modern method of transportation probably sounds the death knell of the carriage as the presidential conveyance on Inauguration Day."

Federal Aid or Federal Construction

While the presidential election of 1920 was underway between Republican Senator Harding and Democratic Ohio Governor James M. Cox, the fate of the Federal-aid highway program was uncertain. The program was funded only through Fiscal Year (FY) 1921.

Many highway supporters argued for replacing the Federal-aid highway program with Federal construction of an interstate highway system better suited to the needs of automobiles and the growing number of trucks in the post-war era. This support was partly because of defects that had emerged in the Federal-aid highway program since its start in 1916.

After Senator Harding and his running mate, Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts (future No. 34), won, the American Road Builders Association (ARBA) asked about his views on roads. President-elect Harding replied by a letter that was read to ARBA's annual convention in 1921:

Our civilization depends on communication and transportation, and as it becomes increasingly complex, that dependence increases. Every great community is held together by its means of transportation and so vast a country as ours is the more in need of ample facilities.

He explained that other modes of transportation – railroads, waterways, the new merchant marine – "cannot be of fullest utility unless good roads supplement them." He concluded:

In recent years there has been nation-wide realization of the road problem. We need to devise and adapt means, financial and engineering, to solve it. I believe we shall progress greatly, in the years of peace and prosperity which I am confident lie ahead of us, toward this solution, and such organizations as your own will contribute much to that end.

Although the message was positive, the President-elect did not address the debate between advocates of Federal-aid and national roads.

Harding and Coolidge took office on March 4, 1921. Earlier in the day, when the 66th Congress adjourned earlier in the day on March 4, Senator Charles E. Townsend of Michigan, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Post Offices and Post Roads – and chief Senate backer of national roads –blocked a House bill extending the Federal-aid program beyond FY 1921. What would happen after June 30, 1921, was unknown.

The New York Times reported in April 1921 that the new President "has been for some time making a quiet, but thorough investigation of the highway improvement situation, particularly of various road projects which have been allotted money from the Treasury of the United States:"

The President, it can be stated, is thoroughly alive to the seriousness of this road problem . . . . In his study of the highway problem the disclosure which impressed the President more than any other phase of the question was the fact that enormous sums of money have been expended on roads without any thought of the permanency of those roads. If the President has his way not one dollar of Federal money will be applied in the future to any road, the proper and economical maintenance of which has not been provided for.

The President considers it nothing less than folly for the Government to contribute money toward road projects, which in numerous instances go to pieces in two or three years, leaving to the people a tax inheritance that involves large bond issues.

He met "for some time" on April 8 with Senator Townsend, whose "committee will draft the road bill which will be introduced in the next Congress, and which is expected to eliminate serious defects in the present law." The Times explained:

The President is an enthusiastic advocate of good roads that are really good roads, properly constructed and properly maintained.

It is the view of the President that the Federal Government should not be saddled with the maintenance cost of highways, but that this should be borne by the several States benefited by the roads. In many States the license fees for motor vehicle owners are alone sufficient, the President has been informed, to pay the maintenance cost of the highways.

In conversation with visitors today the President was quoted by one of the visitors as having said that some of the roads to which he has given careful consideration have cost more than $25,000 per mile, which, he explained, is higher than the cost of the finest railroad.

The Federal-Aid Road Act of 1916, which established the Federal-aid highway program, stated that, "To maintain the roads constructed under the provisions of this act shall be the duty of the States, or their civil subdivisions, according to the laws of the several States." If a road was not properly maintained and the deficiency was not corrected within 4 months of notification, the Secretary of Agriculture "shall thereafter refuse to approve any project for road construction in said State, or the civil subdivision thereof, as the fact may be, whose duty is to maintain said road, until it has been put in a condition of proper maintenance." The term "properly maintained" was defined in the 1916 law as: "the making of needed repairs and the preservation of a reasonably smooth surface considering the type of road, but shall not be held to include extraordinary repairs, nor reconstruction."

President Harding had called for a special session of Congress to address the economic disruption that had lingered during the rough transition from war to peace. Shortly before delivering his opening speech, he met with auto industry advocates of national highways. Roy Chapin, chairman of the Highways Committee of the Hudson Motor Company, told the President that the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce, which Chapin headed, opposed continuing the Federal-aid highway program in its present form because the public interest was not fully served by the large expenditures.

The President made clear that he was concerned about highway maintenance, and would insist on a strong provision on the subject in future highway legislation. He thought the entire proceeds from vehicle license fees should be devoted to maintenance.

Chapin and his committee also met with Chief Thomas H. MacDonald of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR), Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace, and Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon. The meeting prompted MacDonald to outline his position:

The task today is to provide highway service; we cannot afford to wait for the construction of new and modern types of highways. The maintenance should be carried forward now on roads improved and unimproved. The returns will more than compensate the cost. If there is one problem which the road builders of the United States as a whole must learn it is that of highway maintenance.

On April 12, the President addressed the joint session of Congress. He discussed many topics, including several transportation issues, which he said were of "great interest to both the producer and consumer – indeed, all our industrial and commercial life, from agriculture to finance." After discussing railroad issues, he turned to the highways which, he said, "deserve your most earnest attention, because we are laying a foundation for a long time to come, and the creation is very difficult to visualize in its great possibility." He continued:

The highways are not only feeders to the railroads and afford relief from their local burdens, they are actually lines of motor traffic in interstate commerce. They are the smaller arteries of the larger portion of our commerce, and the motor car has become an indispensable instrument in our political, social, and industrial life. There is begun a new era in highway construction, the outlay for which runs far into hundreds of millions of dollars. Bond issues by road districts, counties, and States mount to enormous figures, and the country is facing such an outlay that it is vital that every effort shall be directed against wasted effort and unjustifiable expenditure. The federal government can place no inhibition on the expenditure in the several States; but, since Congress has embarked upon a policy of assisting the states in highway improvement, wisely, I believe, it can assert a wholly becoming influence in shaping policy.

With the principle of federal participation acceptably established, probably never to be abandoned, it is important to exert federal influence in developing comprehensive plans looking to the promotion of commerce, and apply our expenditures in the surest way to guarantee a public return for money expended.

Large federal outlay demands a federal voice in the program of expenditure. Congress can not justify a mere gift from the federal purse to the several states, to be prorated among counties for road betterment. Such a course will invite abuses which it were better to guard against in the beginning.

The laws governing federal aid should be amended and strengthened. The federal agency of administration should be elevated to the importance and vested with authority comparable to the work before it. And Congress ought to prescribe conditions to federal appropriations which will necessitate a consistent program of uniformity which will justify the federal outlay.

I know of nothing more shocking than the millions of public funds wasted in improving highways, wasted because there is no policy of maintenance. The neglect is not universal, but it is very near it. There is nothing the Congress can do more effectively to end this shocking waste than condition all federal aid on provisions for maintenance. Highways, no matter how generous the outlay for construction, cannot be maintained without patrol and constant repair. Such conditions insisted upon in the grant of federal aid will safeguard the public which pays and guard the federal government against political abuses, which tend to defeat the very purposes for which we authorize federal expenditure.

Engineering News-Record was impressed that the President had devoted more space to highways "than was ever before devoted to the subject in a Presidential address" and thought his statements were "sound wherever his meaning is not open to debate." The problem was that President Harding's comments were ambiguous on Federal-aid versus national highways, as The New York Times pointed out in an article that began, "The attitude of the Harding Administration toward national highway improvement is expected to raise it to one of the leading issues of the day."

Senator Townsend soon introduced a watered down version of his bill to establish a Post Roads and National Highway Commission. In a compromise, the bill proposed to replace BPR and designate a national interstate system that, unlike earlier versions, called for the State highway departments to build. In addition, the bill reflected President Harding's views on maintenance. It provided that, "no project shall be approved by the commission in any State until the State has made adequate provision for the maintenance of all highways selected by the commission in that State." If a State, upon notice of a maintenance deficiency, does not place the road in "proper condition of maintenance" within 100 days of the notice, the commission would make the repairs and charge the State by reductions in its apportionment of Federal-aid funds.

By mid-1921, Congress had several road bills to consider. They reflected the wide range of views on national roads versus Federal-aid, but as reflected in Senator Townsend's new bill, a middle view between the extremes seemed to be gaining strength.

Several factors were at play. Chief MacDonald had stabilized the Federal-aid highway program and established positive, cooperative relations among State highway officials and other good roads interests. Further, many of the problems that had hindered the Federal-aid highway program since its inception in 1916 had been resolved. The biggest problem had been the war, which reduced construction workers, supplies, and railroad shipments of road building material, thus delaying full implementation of the new program. Following the armistice on November 11, 1918, these problems were resolved as the country returned to a peacetime economy.

Moreover, the Post Office Appropriation Act of February 28, 1919, had addressed some program defects. For example, the 1916 Act limited Federal-aid to all "rural post roads," a term that as initially defined prevented the use of the funds on long-distance roads where mail was transported by railroads. The 1919 change broadened the definition, prompting Senator Charles S. Thomas of Colorado to complain that the funds could be used to improve "every cattle trail, cow path, and every right of way in the United States," but the new definition became law.

The Federal Highway Act of 1921

After extensive debate, Federal-aid prevailed. The final bill reflected a compromise that was acceptable to long-distance road advocates and supporters of the Federal-aid concept. BPR survived. Federal-aid highway funds would now be restricted to roads contained in a designated system that would comprise up to 7 percent of all rural public roads in each State. Three-sevenths of the system must consist of roads that were "interstate in character." Up to 60 percent of the Federal-aid highway funds could be expended on these primary or interstate roads. The remainder of the 7-percent system would consist of secondary or intercounty roads.

The legislation also addressed the President's concern by strengthening the maintenance provision of the 1916 Act. Section 2 of the new bill redefined "maintenance" to mean "the constant making of needed repairs to preserve a smooth surfaced highway." Under Section 14, a State highway department would receive a 90-day notice of a failure to maintain a Federal-aid highway. If the road was not "placed in proper condition of maintenance" during that period, the Secretary "shall proceed immediately to have such highway placed in a proper condition of maintenance and charge the cost thereof against the Federal funds allotted to such State, and shall refuse to approve any other project in such State" until the State reimbursed the Federal highway fund for the amount expended.

The importance of the bill was understood at the time. And so, on November 9, 1921, President Harding, No. 40, signed the landmark bill in an elaborate ceremony that was staged to allow a motion picture of the event to be made. After several speeches, Senator Townsend handed the President a specially wrought pen to sign the bill. Much to the dismay of AASHO, which had supported the Federal-aid approach that had prevailed, the pen ended up with AAA, which favored the Federal construction plan that was dropped.

Photo courtesy of the Eisenhower Library

Chapin and others who shared his views were disappointed the legislation did not create a national program, but he said, "the law as it stands marks a distinct step forward in the evolution of our highway policy." Senator Townsend called it "the most progressive step ever taken by Congress in aid of good roads." As it turned out, the 1921 Act not only settled the dispute between the advocates for Federal-aid and Federal construction, but put the Federal-aid highway program on a "system" basis that would remain at the core of the program. In addition, it launched the country on what contemporary observers called the third Golden Age of Road Building, after the ancient Romans and the 19th century French. By the mid-1930s, the country had an interstate system consisting mainly of two-lane, paved U.S. numbered highways.

President Harding also signed the Post Office Appropriation Act, 2023, on June 19, 1922. It included authorizations for the Federal-aid program through FY 1925, with the funds "authorized to be appropriated." The phrase meant that approval of a project "shall be deemed a contractual obligation of the Federal Government," even if an appropriation act had not yet been approved. The idea, known as "contract authority," remains a key feature of the Federal-aid highway program.

In addition, on June 4, 1923, President Harding participated in the dedication ceremony on the Ellipse, south of the White House, for the Zero Milestone ("Point For The Measurement of Distances From Washington on Highways of The United States"). Thousands of people gathered for the event. It marked the starting point for the U.S. Army's first motor transcontinental convoy in 1919 on which Dwight D. Eisenhower – then a little-known tank instructor who never made it to Europe during the Great War and thought his military career probably was over – learned the value of improved roads. Harding said, "Thus far, the motor vehicle has seen an evolution so rapid that the highway has not kept pace with the vehicle. But . . . a truly wonderful progress has been made in highway construction until now the interstate system of approximately 200,000 miles begins to assume definiteness." The Zero Milestone remains in place today, baffling tourists who mainly see it as a place to place their things on while taking photographs of the White House.

Two weeks later, on June 20, President Harding embarked on the Voyage of Understanding from which he never returned.

The Judgment of History

The truth is that presidential historians judge Presidents by more than their attitude about roads. For example, while they acknowledge President Roosevelt's initiation of the idea of an Interstate System and President Eisenhower's role in launching its construction, historians base their lofty ranks primarily on many other considerations.

Historians and biographers often try to rehabilitate the reputations of our lower-ranked Presidents. In the case of President Harding, they may want to start the rehab with his road accomplishments. Otherwise, President Harding's great role in the history of road building at a moment in time on November 9, 1923, will be overshadowed by negatives that left him after 2 and a half years at No. 40, just slightly better than President Harrison, who needed only a month to reach No. 41.