A Moment in Time: Don't Blame President Eisenhower

by Richard Weingroff / FHWA News 2024

The urban segments of the Interstate System have been controversial virtually from the start of construction after President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 on June 29. The expressways were intended as congestion-busting transportation arteries to help revive the central business districts, but families didn't want to be displaced from their homes and neighborhoods, while business owners felt the same way about their stores. As for the Black communities in every big city, living "separate but equal" lives apart from the White communities, well, they turned out to be living, according to highway engineers and city planners, in exactly the best place for urban expressways. They, also, didn't want to be displaced, but in many cases lacked the political muscle to fight it, especially in the early years.

Today, all these years later, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Federal Highway Administration have many concerns, including finding ways to restore the equity destroyed by the urban expressways that plowed through Black neighborhoods. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg explained that, "if Federal dollars were used to divide a neighborhood or a city, Federal dollars should be used to reconnect it." The point, he added, is that "transportation should always connect, never divide."

There are many reasons why the expressways ran through, or tried to run through so many Black neighborhoods around the country, and whatever the intentions of the engineers involved, the one man who should not be blamed is President Eisenhower. At a moment in time on April 6, 1960, he made clear that the urban expressways were not part of his vision for "broader ribbons across the land."

Before President Eisenhower

The Interstate System can be traced to the 1930s. Visionary proposals for massive, straight-as-an-arrow transcontinental toll superhighways received extensive publicity, and even caught the eye of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. One of the most publicized was by T. E. Steiner, a businessman from Wooster, OH, who proposed the toll Transcontinental Stream Lined Super Highway on as straight a line as possible from Boston to San Francisco, with three connections to southern destinations. I am confident," Steiner said about one of the most appealing aspects – to government officials – of his proposed $12 billion project, "that highways of this kind would never cost the government a cent."

In 1938, ideas such as Steiner's concept or proposals for networks of toll superhighways prompted President Roosevelt to ask Chief Thomas H. MacDonald of the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) to study creation of a limited network of toll superhighways. (See "The Roosevelt Map".) Learning of the internal study, Congress included a provision in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1938 requesting a report on just such a network. The resulting 1939 report, Toll Roads and Free Roads, rejected the toll option because revenue from projected traffic in many locations would not support retirement of the needed bonds.

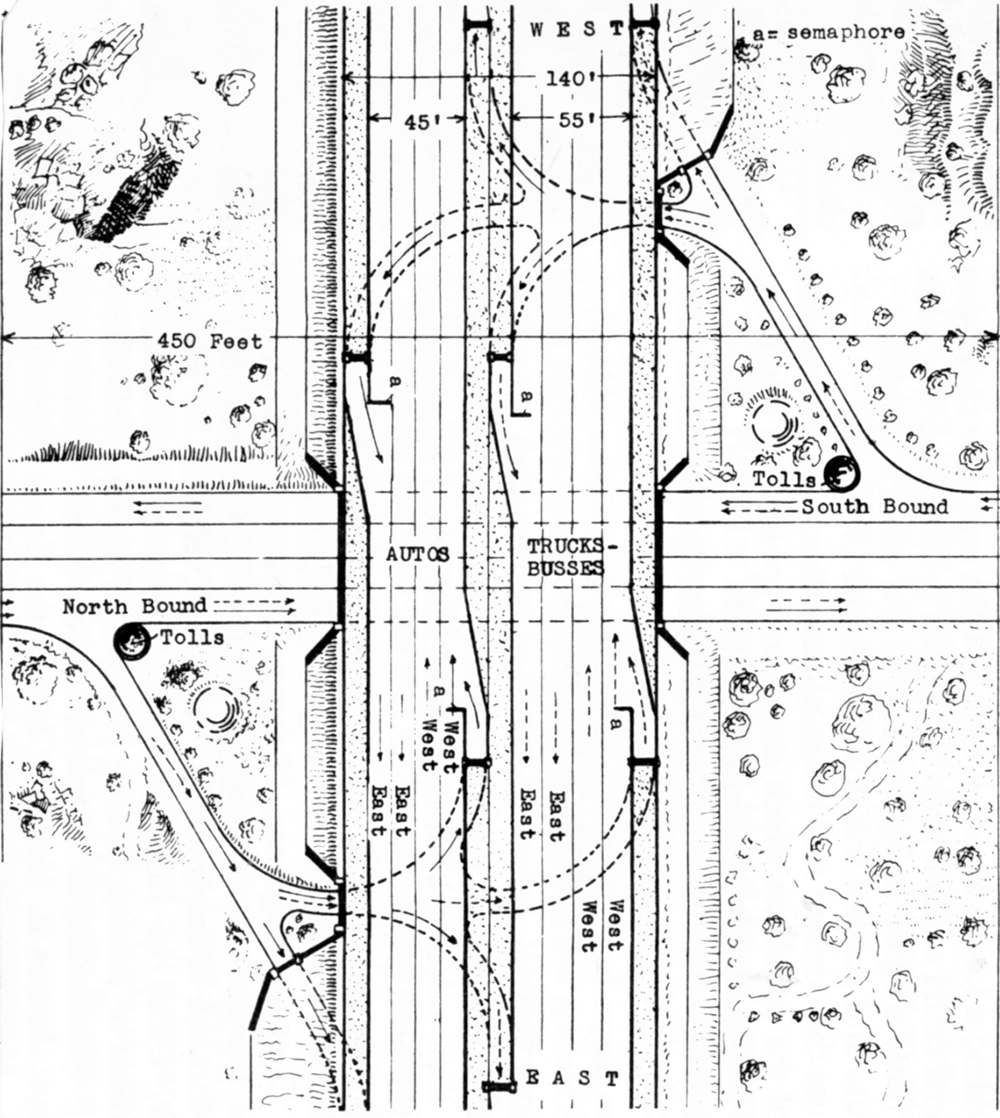

However, BPR did not want to be entirely negative, so it included "A Master Plan for Free Highway Development" that provided the first formal look at what became the Interstate System." It suggested a national network of about 26,700 miles generally in the alignment of existing U.S. numbered highways. BPR wanted to avoid words such as "transcontinental" and "superhighway." It preferred "interregional" because most trips outside cities were regional. BPR explained in considerable detail, that urban expressways were an important part of the proposed network. They were essential to relieving congestion, allowing traffic to bypass downtowns, improving safety, and in some cases, replacing slums and blighted areas.

The report stirred up interest in the press and in Congress, but did not result in legislation. In 1941, President Roosevelt appointed a National Interregional Highway Commission that prepared a report, Interregional Highways, that was delayed by the war. He finally transmitted it to Congress in January 1944. Like its predecessor, the report outlined the need for a national network of interregional expressways, but went into even greater detail about the proposed urban expressway arterials, circumferentials, and connections. President Roosevelt endorsed its concepts and estimated that construction of the rural and urban sections would cost $750 million a year for 10 to 20 years, "dependent upon the availability of manpower and materials, and upon other factors." He added, "The over-all expenditure would be approximately evenly divided between urban and rural sections of the system."

The report prompted Congress to include a provision in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 calling for the Federal road agency to work with the State highway departments to designate a 40,000-mile "National System of Interstate Highways." They would cooperate to designate 37.600 miles of rural interstate mileage in August 1947, including a single line carrying the routes through the big cities. That left room for designation of about 2,300 miles of urban expressways. The 1944 Act did not include special funds for the new network, with the result that very little was accomplished in succeeding years.

Eisenhower's Grand Plan

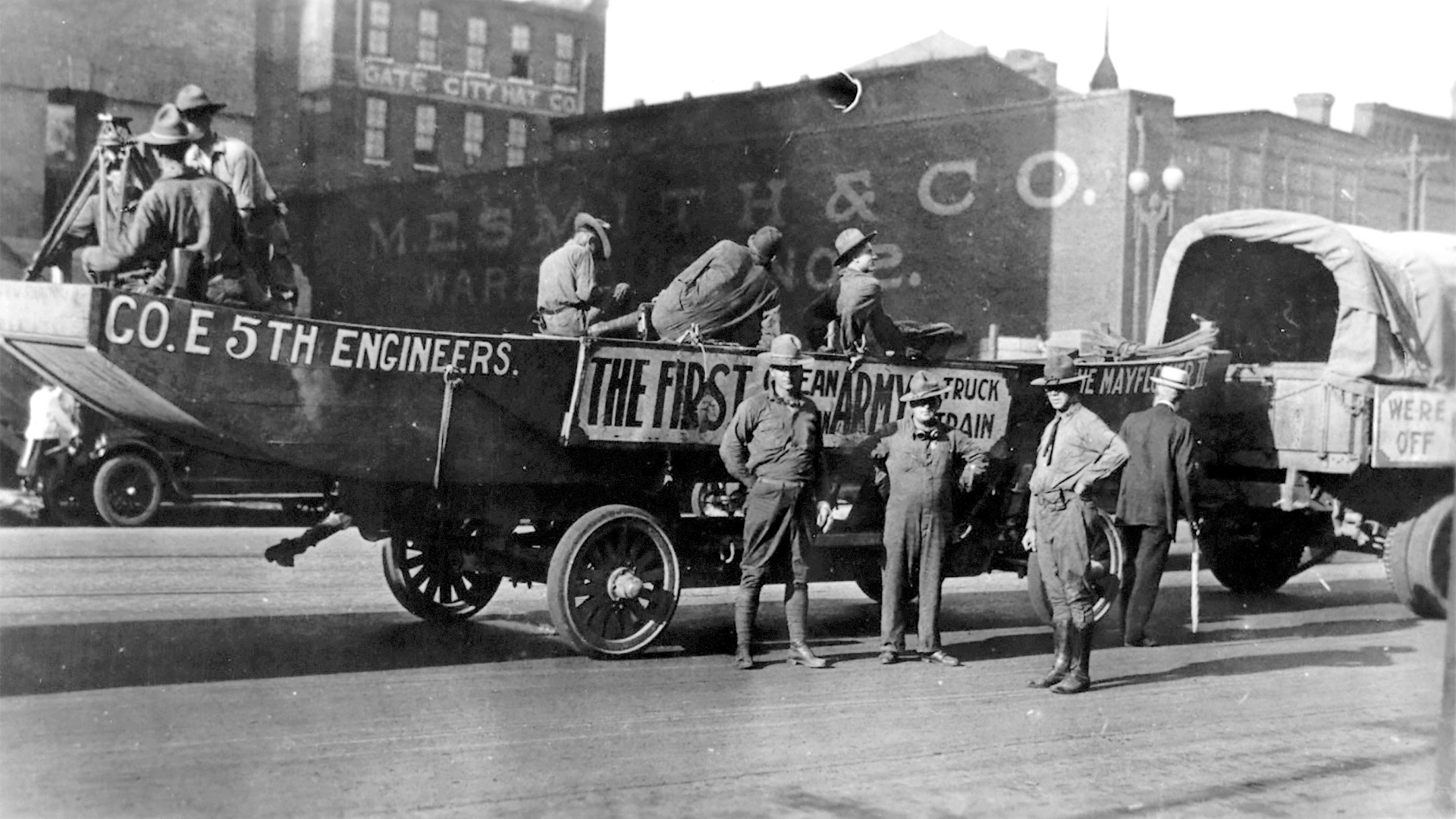

Eisenhower was busy elsewhere during the 1940s, as you know, and when he became President on January 20, 1953, he had urgent business to attend to, such as ending the Korean War. But in 1954, he decided the time had come to do something about the Nation's roads. In 1919, he had been a participant in the U.S. Army's first transcontinental convoy of military vehicles (the Ellipse in Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg, PA, where the convoy took the Lincoln Highway all the way to San Francisco). He experienced the ruts, mud, "gumbo," inadequate bridges, narrow roadways, sand storms, and every other challenge facing interstate motorists at the time. Having also seen the autobahn network of expressways that Germany had built mainly in the 1930s, he understood their value to Germany during the war, to the allies as the war ended, and in the post-war period. "The old convoy," he wrote in a post-presidential memoir, "had started me thinking about good, two-lane highways, but Germany had made me see the wisdom of broader ribbons across the land."

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1952, signed on June 25 by President Harry S. Truman, had authorized a token amount of funds for the Interstate System, $25 million a year for 2 fiscal years at the traditional 50-50 State-Federal matching ratio, and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1954, which President Eisenhower signed on May 5, authorized $175 million a year for 2 years, with an increased Federal share of 60 percent. Even as he signed the bill, he knew that much more was needed to realize his vision. Professors Mark H. Rose and Raymond A. Mohl explained in the third edition of Interstate: Highway Politics and Policy Since 1939, that, "Since at least mid-February, 1954, Eisenhower had believed that the federal government should boost road spending in order to accommodate traffic." More traffic would mean "greater convenience . . . greater happiness, and greater standards of living." He wanted a "dramatic" plan to get $50 billion in "self-liquidating highways" underway – that is, highways that would pay for themselves without adding to the deficit.

In July 1954, President Eisenhower intended to deliver a speech to the Nation's governors about his Grand Plan for highway improvement. When a death in the family prevented him from attending, he gave his notes to Vice President Richard M. Nixon, who delivered the speech. The President called for "a grand plan for a properly articulated system that solves the problems of speedy, safe, transcontinental travel – intercity communication – access highways – and farm-to-market movement – metropolitan area congestion – bottlenecks – and parking." By "articulated," he meant that each level of government – the Federal Government, State governments, and local governments – should launch a program to improve its roads. Basically, the Interstate System was the Federal responsibility.

While White House officials debated the details, President Eisenhower called on his friend, advisor, and associate, retired General Lucius D. Clay, U.S. Army, to head a public committee to develop proposals for a national highway improvement program. The committee proposed to set up a Federal corporation to issue bonds to pay the recommended 90-percent Federal share of the estimated $27 billion Interstate System. Of that total, about $4 billion was for urban connectors. The bonds would be retired by dedicating the existing Federal tax on gas and lubricating oil to that purpose; up to then, the tax revenue was used for general government expenditures, not tied to the highway program.

On February 22, 1955, President Eisenhower submitted the highway plan to Congress. His transmittal letter included this apt justification: "Together, the united forces of our communication and transportation systems are dynamic elements in the very name we bear – United States. Without them, we would be a mere alliance of many separate parts."

Congress was supportive of the highway network, but not the Clay Committee's financing mechanism. As a result, Congress adjourned in August 1955 after rejecting not only the President's financing proposal but other highway user tax-based proposals. The problem was that everyone supported the highways, but no one wanted to pay for them.

Soon after Congress adjourned, President Eisenhower said, "The nation badly needs new roads," and added, "Adequate financing there must be, but contention over the method should not be permitted to deny our people these critically needed roads." In a memoir, he wrote that at the time, he realized that the Clay financing plan he had endorsed was dead, but "I grew restless with the quibbling over methods of financing. I wanted the job done."

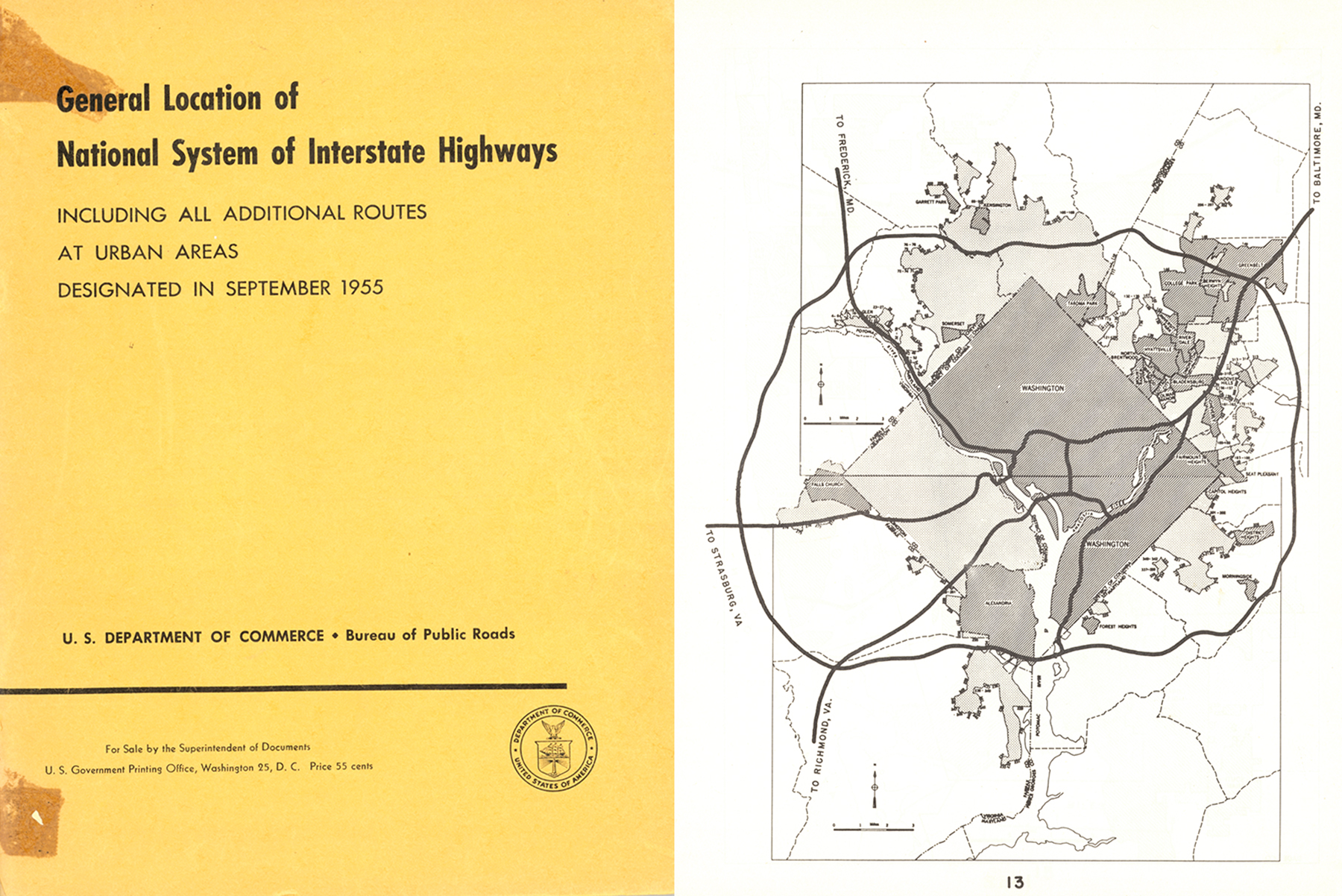

In September 1955, BPR approved maps showing the general location of Interstate routes designated in urban areas. Each Member of Congress received a copy of BPR's Yellow Book, so called because of the color of the cover. It contained maps showing the Interstates in blank outlines of the main cities. The publication was publicized around the country, with each newspaper emphasizing the routes designated in its reading area.

Over the winter, the White House met with all parties and worked out an agreement on a plan of highway user taxes to pay for the new program. Congress approved the proposal in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The key was creation of the Highway Trust Fund, a crediting mechanism to keep track of incoming revenue from the agreed upon highway user taxes that would finance the new construction program and the regular Federal-aid highway program. The Act also made a Federal commitment to pay 90 percent of the "cost to complete" each designated Interstate highway to full design standards. This commitment meant that whatever it cost to construct the routes to full design standards, the Federal Government would pay 90 percent (and a little higher percentage on a sliding scale in States with large amounts of public land).

What President Eisenhower Didn't Know

President Eisenhower was not aware of the earlier stages in development of the Interstate concept. He had never heard of the two reports - Toll Roads and Free Roads (1939) or Interregional Highways (1940) that inspired the Interstate System and that contained extensive descriptions of how to fit Interstate expressways into cities. He was, instead, very familiar with Germany's autobahn network that was an entirely rural network.

Unlike the President, Members of Congress were well aware of the urban segments as they debated the proposed program in 1955 and 1956. Mayors testified enthusiastically about the benefits their cities would enjoy from the urban Interstates. The Yellow Book showed each Member of Congress where expressways might be located in their cities. Newspapers emphasized the rural and urban locations.

And once construction began, the urban Interstate segments were discussed extensively in newspapers and magazines – both favorably in anticipation of the benefits they would bring and negatively in response to the controversies they provoked. If President Eisenhower read the newspapers from the Washington area alone, he would have seen many articles about the controversial Interstate network in the city and surrounding areas.

But he didn't know.

The Shock of Discovery

Historians have speculated on how the President discovered the truth. Stephen Ambrose, in his Eisenhower biography, suggested that the President's motorcade was delayed in 1959 on a trip from the White House to Camp David by "a deep freeway construction gash in the outskirts of metropolitan Washington. Surprised and appalled by what he saw, he called Maurice Stans, director of the Bureau of the Budget, and asked for an explanation."

Ambrose explained that, "In Eisenhower's vision, the superhighways were not supposed to have gone into the cities, but only around them, as in Europe. His objections were not sociological – few if any of those associated with the building of the Interstates anticipated the tremendous effect the urban freeways would have on housing patterns, schools, inner-city conditions, the spread of the suburbs, or the other nearly limitless ways in which the four- and six- and eight-lane highways changed the face of urban America. Eisenhower's objections were to the cost, not the result."

At the time, funding for the program was a major concern. A brief recession in 1958 had prompted Congress to increase the rate of expenditure on the Interstate System without increasing income, prompting the Highway Trust Fund to run a deficit.

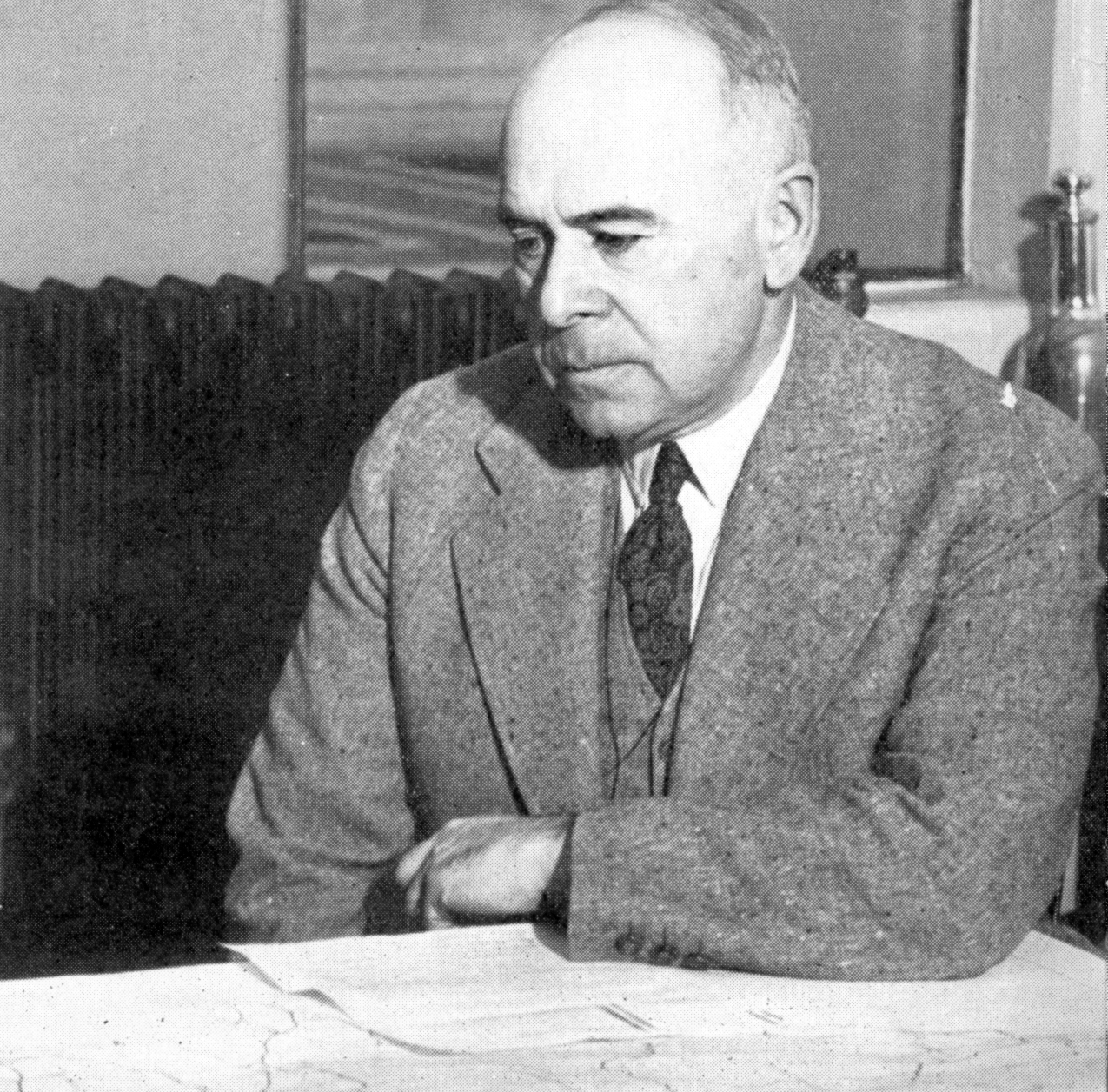

In early 1959, General John H. Bragdon (U.S. Army, retired) and Stans began exploring options for addressing the shortfall, such as by reducing the number of interchanges, building some rural routes as turnpikes, and eliminating the number of urban Interstate highways. In a letter to the President on June 17, 1959, General Bragdon suggested instructing BPR to examine the feasibility of routing the Interstates "close by but not through central cities, using ingress and egress routes to congested portions."

On July 2, the President sent instructions to General Bragdon, Stans, and Secretary of Commerce Frederick H. Mueller, who had taken office only 3 days earlier on June 30, 1959, as head of the department that included BPR. The letter called for a broad review of the Federal highway program. The study should cover, but not be limited to, "intra-metropolitan area routing including ingress and egress, interchanges, grade separations, frontage roads, traffic lanes, utility relocations, and engineering design"; delineation of Federal, State, and local responsibilities for financing, planning, and supervising the highway program; ways "for improving coordination between planning for Federal-aid highways and State-Local planning, especially urban planning"; and ways to minimize the Federal cost of the highway program. Overall, "Priority should be given to those aspects of the program where maximum savings can be effected."

General Bragdon had been involved in the planning stages in 1954 and 1955, and had generally favored a limited rural network financed with tolls – but lost every internal battle. As Professor Gary T. Schwartz put it, "Bragdon was handicapped by an ineptness at bureaucratic maneuverings . . . . Bragdon's entire White House career was marked by frustrations and failures." But now, given the President's concerns, he had a second chance to implement his original ideas. He had 10 staffers to conduct the study, plus consultants hired as needed and personnel from BPR to help.

The President Decides

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1959, signed by the President on September 21, addressed the immediate financial problem by a temporary increase of the gas tax to 4 cents. (The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1961, approved June 29, made the change permanent.)

Even with the immediate funding problem addressed, General Bragdon's study continued on.

He briefed the President on November 30, 1959. A summary of the meeting stated that the President confirmed that while he favored a transcontinental network, he considered routing within cities as primarily a city responsibility. "The President was forceful on this point." General Bragdon recommended eliminating routes in cities that were primarily for local needs and were unnecessary for intercity connections, or at least require the cities to pay their part. He cited "an example in northwest Pennsylvania of the too-frequent spacing of interchanges" on I-90 in the Erie area and the "extremely high costs" of urban Interstates, such as the I-95 Delaware Expressway through Philadelphia. Some segments, he said, could be built as toll roads to reduce the cost to taxpayers. The President indicated he liked the idea of "self-liquidating projects" that would be possible only if developed as toll facilities.

The launching of Bragdon's review set off alarms throughout the highway community. During the President's press conference on March 16, 1960, Lowell K. Bridwell, a transportation reporter for Scripps-Howard Newspapers (and a future Federal Highway Administrator, 1967-69) asked about the survey's principal findings "and whether you have made any administrative changes as a result." The President called the study "a personal advisory thing to me." He had asked General Bragdon "what are we doing and does it seem to accord with the law and the legislative history." But as for the results, "it's a matter between General Bragdon and myself."

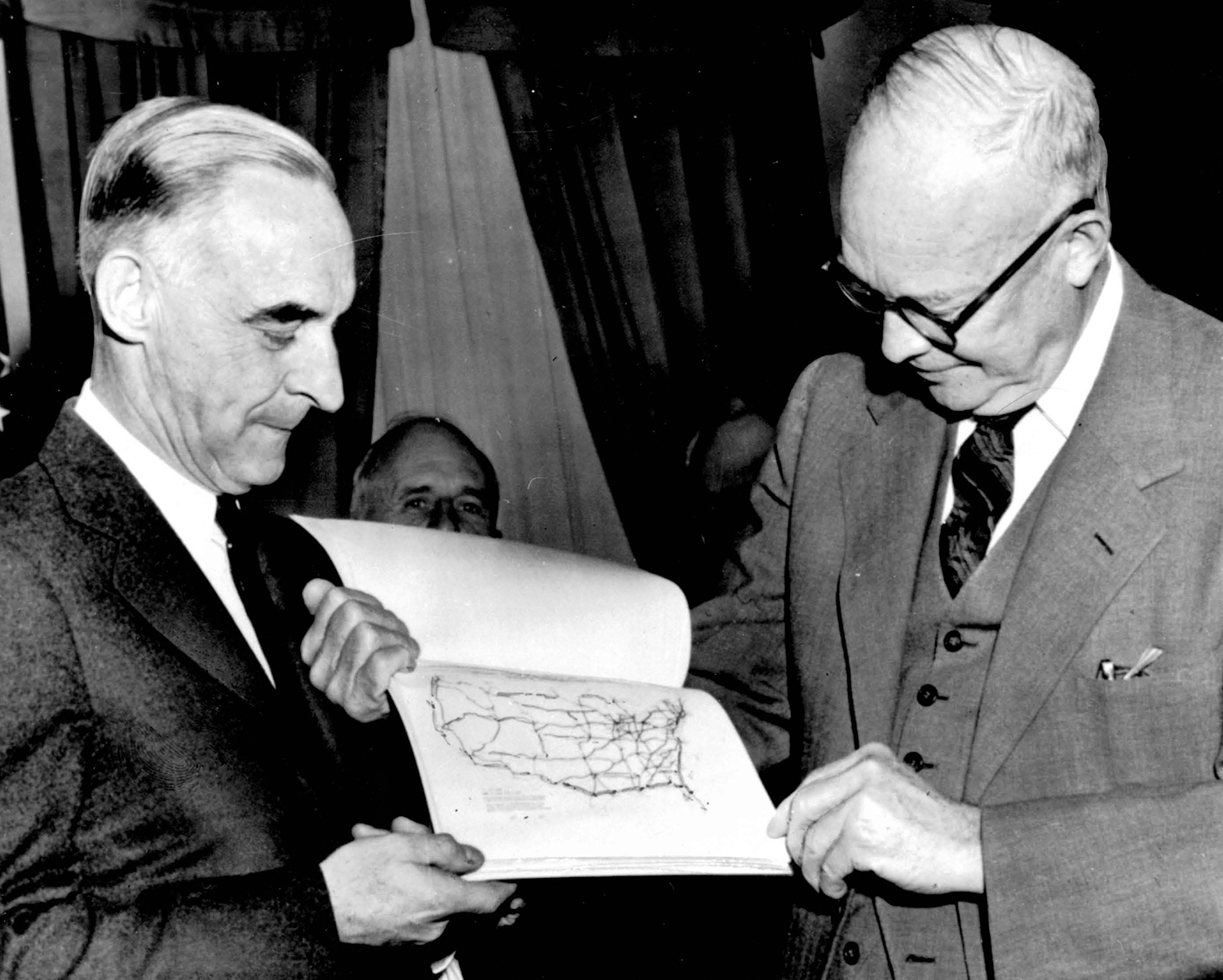

At 10:35 on April 6, 1960, the President attended a 55-minute meeting with General Bragdon and his aide Colonel John A. Meek; Secretary Mueller; Federal Highway Administrator Bertram D. Tallamy (1957-1961); and White House aide Robert Merriam. Bragdon had brought 17 charts to describe his findings, an exercise that seemed to irritate the President because of the time involved. According to a memorandum for the record, Bragdon boiled his ideas down to two suggestions:

- Send to the Congress the proposal for permissive toll roads on the Interstate. This would be the only legislation at this time.

- Quietly, and insofar as possible, administratively implement the revised criteria cited in the Report.

The President then said that his staff had told him that while the legislation was under consideration in 1955 and 1956, the cities had been told they would get adequate consideration on a "per person" basis in view of the taxes they paid and that, in fact, "that they were to get more consideration since they paid much more in taxes per person than persons in rural areas." He also had heard about the Yellow Book maps of urban routes, but had not yet seen it. (The notes indicate Mueller handed him a copy, although Tallamy would later recall he did so.) The urban funding and the Yellow Book, the President understood, "were the prime reasons the Congress passed the Interstate Highway Act. In other words, the Yellow Book depicting routes in cities had sold the program to the Congress."

He then said the idea of running Interstate routes through the congested cities was "entirely against his original concept and wishes." He had studied the Clay Committee report carefully, but didn't see anything in it about an "extensive intra-city route network." Those who had not advised him on it and those who steered the program in that direction "had not followed his wishes." Tallamy pointed out that the Interstate concept was nothing new, that it dated to 1939. But the President said that "while that might be so, he had not heard of it and that his proposal for a national highway network was his own."

He was disappointed that the program developed "against his wishes," but concluded that it had reached the point "where his hands were virtually tied." On that note, the meeting ended at 11:20 a.m. "due to other appointments."

Before Bragdon could submit a final report, President Eisenhower appointed him to the Civil Aeronautics Board later that month. Bragdon's successor, Floyd Peterson, submitted a 12-page report to the President on January 17, 1961, just days before Senator John F. Kennedy took the oath of office as the new President of the United States. Professor Schwartz commented that the report "was in both style and substance a classic of bureaucratic aridity." It was quickly forgotten as the new Administration took office.

The News is Out

On April 13, 1960, Representative Gordon Scherer of Cincinnati, OH – who was described in the contemporary American Road Builder magazine as "the leading Republican highway advocate in the House" – wrote to Secretary Mueller to request information on reports that the Eisenhower Administration might de-emphasize the Interstate System in urban areas.

Secretary Mueller replied on April 15. "The administration has no intention whatever of abandoning any of the routes presently designated as general corridors of traffic – in urban or in rural areas." He added that the Interstate routes could not solve all urban traffic problems, but they were part of the solution, along with "the Federal-aid urban arterial highways and other major city and State thoroughfares, combined with both rail and rubber mass transportation and, to a considerable degree, with both air and water facilities."

Over the years, the urban Interstates have been criticized for many reasons, including their disruptive impact on minority neighborhoods. Ways to reestablish the equity that the highways disrupted are being studied in cities around the country and in the DOT.

But don't blame President Dwight D. Eisenhower. At a moment in time on April 6, 1960, he made clear that the urban Interstates were contrary to his vision even as he acknowledged that it was too late to do anything about them.